USA. 1977.

Crew

Director/Screenplay/Visual Effects Concepts – Steven Spielberg, Producers – Julia Phillips & Michael Phillips, Photography – Vilmos Zsigmond, Music – John Williams, Photographic Effects – Douglas Trumbull & Richard Yuricich, Special Effects – Roy Arbogast, Alien – Carlo Rambaldi, Production Design – Joe Alves. Production Company – Columbia.

Cast

Richard Dreyfuss (Roy Neary), Francois Truffaut (Claude Lacombe), Teri Garr (Ronnie Neary), Melinda Dillon (Jillian Guiler), Cary Guffey (Barry Guiler), Bob Balaban (David Laughlin)

Plot

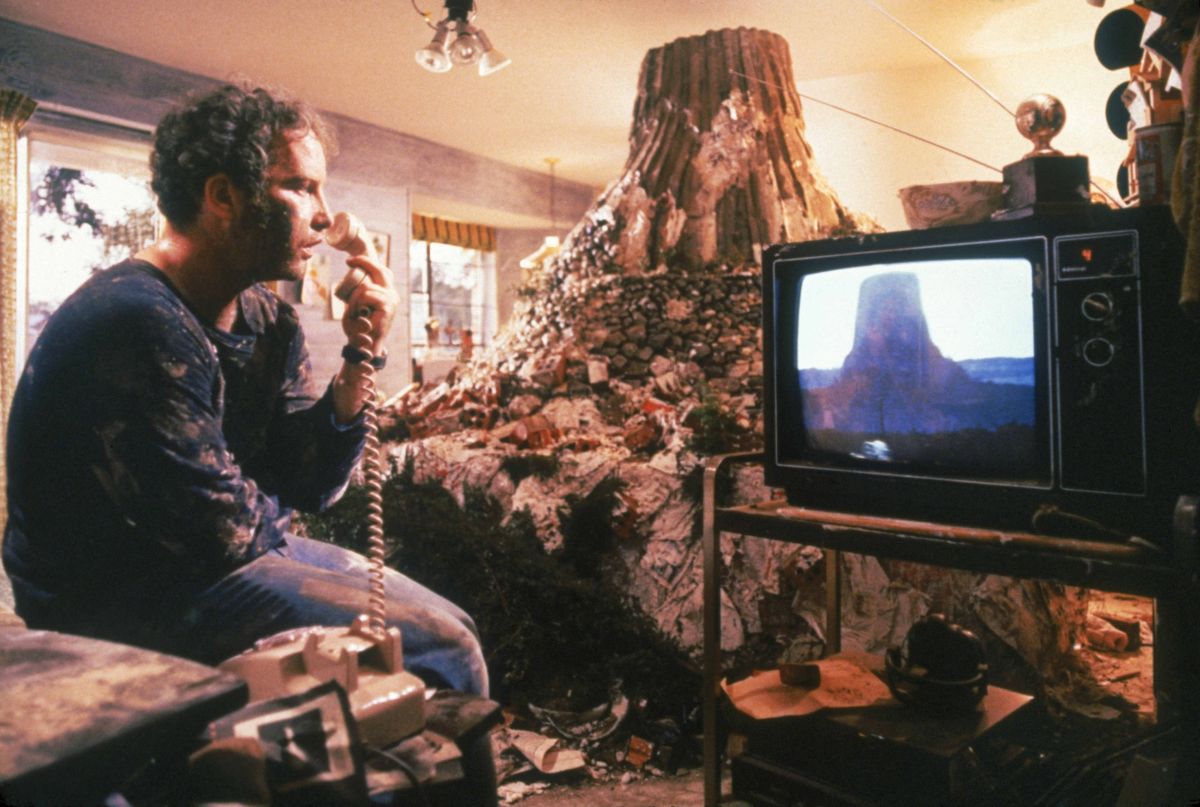

A rash of UFO sightings suddenly occur around the world. In Indiana, linesman Roy Neary encounters several UFOs while out on a remote country road. Afterwards, Neary becomes obsessed with what he saw, driven to recreate an image left in his mind. His obsession drives his wife and children to leave. He persists with it, following the summons that draws him towards the first meeting between mankind and alien at a rendezvous site in Wyoming.

When Steven Spielberg made Close Encounters of the Third Kind, nobody knew what to expect. Spielberg had hit the all time No.1 Box-Office spot with Jaws (1975) two years previously, but nobody knew if box-office lightning would strike twice for the then 27 year-old wunderkind. Indeed, the entire financial future of Columbia Pictures was at one point riding on the whether or not Close Encounters of the Third Kind would be a success. The film was made under a complete veil of secrecy, which both infuriated and spurred the press on.

Well, Close Encounters hit big, Columbia survived and Spielberg’s name was confirmed. Along with Star Wars (1977), which had been released seven months ealier, directed by Spielberg’s good friend George Lucas, 1977 suddenly became the year when science-fiction was a phenomenon. Science-Fiction had never been big box-office up to that point but in 1977, thanks to these two films, it suddenly became a runaway phenomenon – and one that still continues to this day. The importance of Close Encounters of the Third Kind has faded somewhat two decades later but at the time it was seen as every bit as important and influential as Star Wars was.

Steven Spielberg’s films are filled with a childlike awe. The entirety of Close Encounters of the Third Kind is geared towards the climactic last 38 minutes. The playful dances of the beautiful, glowing UFOs over the airfield; the image of the vast cathedralar mothership in blazing towers and buttresses of pure light rising up over the mountain, dwarfing the entire field; the magical duel of music between the mothership and the computerized synthesizer; and of the thin, skeletal alien emerging from the ship, simply come to smile at us, are visions that are extraordinarily beautiful. The special effects displays here are certainly some of the best ever put on screen.

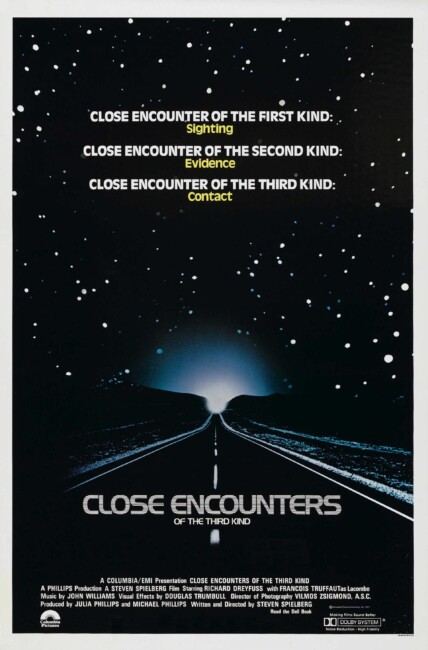

Close Encounters of the Third Kind taps into a 1970s fascination with UFO phenomenon. “We are not alone,” the promotional poster assured us, offering a tantalizing vision of a dark country road with mysterious lights lurking below the horizon. Spielberg, not unlike the UFO cults that sprang up around the time, sees the meeting of human and alien cultures as being an essentially religious experience. Whereas in the 1950s, alien invaders came to threaten our way of life, here they come to save us from it. Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Steven Spielberg’s next venture onto the topic of alien contact – E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) – are really films about faith. For Spielberg, if one can believe upon the universe with an open and child-like heart – some versions of Close Encounters feature the song When You Wish Upon a Star from Pinocchio (1940) playing over the end credits – it will come in beautiful, numinous and shining lights to carry us away from the mundane and now and take us to the stars.

Close Encounters is like a religious vision. (To underscore the point, Spielberg puts a clip of the parting of Red Sea from The Ten Commandments (1956) on tv in the background). The film’s sentiments are not unakin to those of Middle-American churches and their numinous, warm fuzzy belief in The Almighty. Some pro-science science-fiction authors like Isaac Asimov and Harry Harrison condemned the film for its engendering of mysticism and pseudo-science; on the other hand, Ray Bradbury, in a somewhat effusive LA Times review, called Close Encounters of the Third Kind the most important film of our time. And both groups were right in many ways – the number of reported UFO sightings went up dramatically after the film’s release.

Along with George Lucas and Star Wars, Steven Spielberg delivered science-fiction from the soulless bleakness that it became caught up in after 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). 2001 and the films that followed in the 1970s became trapped in a vision of the universe that held transcendental enlightenment but at the same time saw the universe as bleak and coldly alone and a future where humanity was in imminent danger of being swallowed up by technology. Spielberg showed us that the universe could be marvelous and fun. Close Encounters of the Third Kind is the equivalent of sitting in the dark and gazing in wonderment at a starry sky (Spielberg in later interviews revealed the inspiration came from his childhood when his father took him out to see the Perseid meteor shower); 2001, on the other hand, is like gazing up and feeling that whatever else is in the universe is unfathomably cold and distant.

Although, the failing of Spielberg’s vision was something that was eventually demonstrated by various of Spielberg’s imitators in that it was a child-like vision, not an adult one. Humanity’s position in all of this was only one of a child sitting at the footstool of the universe, gazing on in wonder. In Spielberg’s vision you are not meant to ask questions about what was happening – Why do the aliens abduct Barry Guiler and the flyers? Why do they only take Richard Dreyfuss at the end and not the people that have prepared for the journey? Why such a brief visit? Why does their behaviour change so much throughout – alternately mischievous, sinister and infinitely wise? How do they learn Kodaly’s hand signals? Why do the paranoid military suddenly become so trusting of their supposedly benign intentions? Does such a wondrous ship of lights ever manage to blow any bulbs and who takes time off from the eternal playfulness to change them? The truth is that these questions are not meant to be asked, the UFOs are only meant to exist resplendently.

Spielberg had been fascinated with UFOs since he was a child and his father took him out to see a Perseid meteor shower. At the age of sixteen, he put $500 in to make the genesis of Close Encounters with Firelight (1964), a 2.5 film shot on 16 mm about UFOs buzzing his hometown. This actually premiered in a local Phoenix threatre but the film is alas lost today.

Spielberg originally hired Paul Schrader, author of the likes of Taxi Driver (1976) and Raging Bull (1980) and director of Cat People (1982), to write the script. However, when Schrader turned in a script that was centred around government coverup of the truth, Spielberg ditched it and wrote the screenplay himself. This unwittingly marks the essential difference between the two approaches to the UFO film. Paul Schrader turned in a script akin to what later became the model of tv’s The X Files (1993-2002, 2016-8), which is constantly founded in distrust and paranoia. Schrader and Chris Carter’s view of UFOs and the alien is one of embittered betrayal and distrust in the government, they are views of adults who have lost the optimistic innocence that Spielberg believes in. In Spielberg’s vision of Close Encounters by contrast, when the government conducts a coverup conspiracy to make the citizens of Wyoming believe that there is a biospill, they are surprisingly benevolent about it. If Close Encounters of the Third Kind had been made in the 1990s, Richard Dreyfuss and Melinda Dillon would be tortured, eliminated and/or hunted by armed assassins rather than a helicopter merely armed with sleeping gas.

Spielberg displays a deft hand for writing dialogue and directs it in a constantly over-lapping manner that often underscores his flights of wonder with the wittily banal – scientists complaining how the globe they take to trace the coordinates costs $25,000 or the interviewer tagging along taking Neary’s blood-type and particulars as he heads off to return with the aliens. Spielberg has such a deft hand with dialogue that one wishes he would again someday turn his hand to scripting. He never did again up until A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) (2001).

There is a good cast too – Richard Dreyfuss demonstrates his usual cuddly teddy bear-ish boy-at-heart quality in a vehicle that could not be more perfect for such. The immensely warm and likeable Teri Garr walks through the whole film with her eyebrows raised in querulous amusement, even though she seems too nice to be the stressed out wife she is cast as. Spielberg also casts Francois Truffaut, the French director responsible for the likes of The 400 Blows (1959), Fahrenheit 451 (1966), The Bride Wore Black (1967), The Wild Child (1969) and Day for Night (1973), in the only acting part Truffaut ever played outside one of his own films, and Truffaut brings a quiet dignity with his presence.

After previewing Close Encounters of the Third Kind in Dallas in 1977, Steven Spielberg decided to cut several scenes. In 1980, Close Encounters went into major re-release under the title Close Encounters of the Third Kind – The Special Edition and this is the version that is almost exclusively seen in tv screenings today. This print restores seven minutes of the Dallas preview footage, while Spielberg adds six minutes of totally new footage shot especially for the re-release. At the same time, Spielberg has chopped sixteen minutes of other footage from the 1977 general release print – the scenes with Richard Dreyfuss going mad are shorter and the air force conference is gone altogether. However, the new scenes are somewhat disappointing, many just being alternate shots. The completely new sequences are the ones with the stranded ship found left in the Gobi desert and an extension of the climax following Richard Dreyfuss up inside the mothership at the end. (The studio only allowed Spielberg to re-release the film if he added scenes that went inside the mothership). The former neither adds or subtracts anything, but the latter is a nuisance, disturbing the flow of the scene where Lacombe and the alien meet, and having an awful 1940s-ish angelic chorus hearkening away in the background. Both sequences seem unnecessary. Why such a trumpet call had to be made about the film remains mystery. The publicity machine promises a journey into the mothership, to go beyond Close Encounters but the results are underwhelming. All of that said, this is the version that Spielberg considers to be the real Close Encounters of the Third Kind as opposed to the original cinematically released version. This also proved to be the beginning of an entire industry of ‘director’s cuts’ and DVD special releases that proliferated for almost every successful film in the 1990s. In 2007, Spielberg released yet another version to dvd that restores the original print and other deleted footage, but also removes the scenes venturing inside the mothership.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind was spoofed in The Creature Wasn’t Nice (1981), Morons from Outer Space (1985), Monster in the Closet (1986), Canadian Bacon (1995), Casper Meets Wendy (1998), Muppets from Space (1999), Monsters vs Aliens (2009), Paul (2011) and Farmageddon (2019). 5-25-77 (2022) contains a scene where the young hero visits Douglas Trumbull’s studio during the shooting of the visual effects and meets Steven Spielberg.

Steven Spielberg’s other genre films as director are:– Duel (1971), LA 2017 (1971), Something Evil (tv movie, 1972), Jaws (1975), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Twilight Zone – The Movie (1983), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Always (1989), Hook (1991), Jurassic Park (1993), The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) (2001), Minority Report (2002), War of the Worlds (2005), Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), The Adventures of Tintin (2011), The BFG (2016) and Ready Player One (2018). Spielberg has also acted as executive producer on numerous films – too many to list here. Spielberg (2017) is a documentary about Spielberg,

Trailer here