Crew

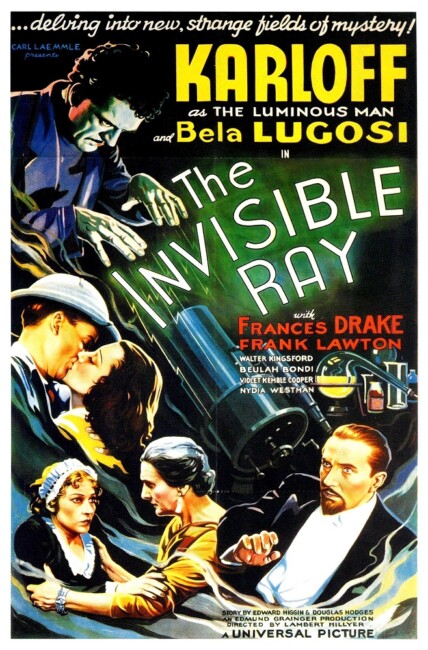

Director – Lambert Hillyer, Screenplay – John Colton, Story – Howard Higgin & Douglas Hodges, Producer – Edmund Grainger, Photography (b&w) – George Robinson, Music – Franz Waxman, Special Cinematographer – John P. Fulton, Art Direction – Albert S. D’Agostino. Production Company – Universal.

Cast

[Boris] Karloff (Dr Janos Rukh), Bela Lugosi (Dr Felix Benet), Francis Drake (Diane Rukh), Frank Lawton (Ronald Drake), Violet Kemble Cooper (Mother Rukh), Walter Kingsford (Sir Walter Stevens), Beulah Bondi (Lady Arabella Stevens)

Plot

Janos Rukh, a scientist ridiculed for his theories, invites a group of people, including colleague Felix Benet, to his laboratory in the Carpathian Mountains. There he demonstrates a new process whereby he is able to capture a beam of light from Andromeda and reverse it to show the Earth millions of years ago. As they watch, they see how a meteorite came down in Africa in the past. Rukh agrees to head an expedition to Nigeria to find the meteorite. There he is able to locate a source of Radium X, a rare element that has unusual powers. However, Rukh becomes infected by exposure to Radium X and begins to glow in the dark, before finding that he kills any living thing he touches. Benet is able to create an antidote that keeps the effects at bay. Rukh is then angered to learn that Benet has sent his notes and samples on to a scientific conference in Paris. Rukh is given credit but Benet pushes on and gains great acclaim for opening up the miraculous healing properties of Radium X. Angered by this and at learning that his wife loves another man, Rukh fakes his own death. He then goes off the antidote and returns to kill each of the members of the expedition with his radioactive touch.

The Invisible Ray was the fourth of eight films that Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, the reigning horror icons of the 1930s and 40s, would play in together up against each other. The two had first appeared in The Black Cat (1934) and were paired up together immediately after in The Raven (1935), as well as in the non-genre musical Gift of the Gab (1934). This was followed by appearances in other genre items like Son of Frankenstein (1939), Black Friday (1940), You’ll Find Out (1940) and The Body Snatcher (1945). As he had been in Universal’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935) the year before, Boris Karloff receives title billing only as ‘Karloff’.

The Invisible Ray was made at the height of the era’s Mad Scientist film and is a fascinating artifact that unconsciously mirrors the attitudes and fear of science that runs through these films. The Boris Karloff Frankenstein (1931) in particular had kicked off a sub-genre of mad science films where it was seen that scientists were defying divine provenance and that their experiments would always produce abominable results or monsters that would go amok and threaten the social order before being brought down by the forces of brute reason in the form of villagers with burning torches. The line “there were some things man(kind) was not meant to know” was never uttered in any film of the era but the nearest we had comes in Violet Kemble Cooper’s line here: “there are some secrets we are not meant to probe.”

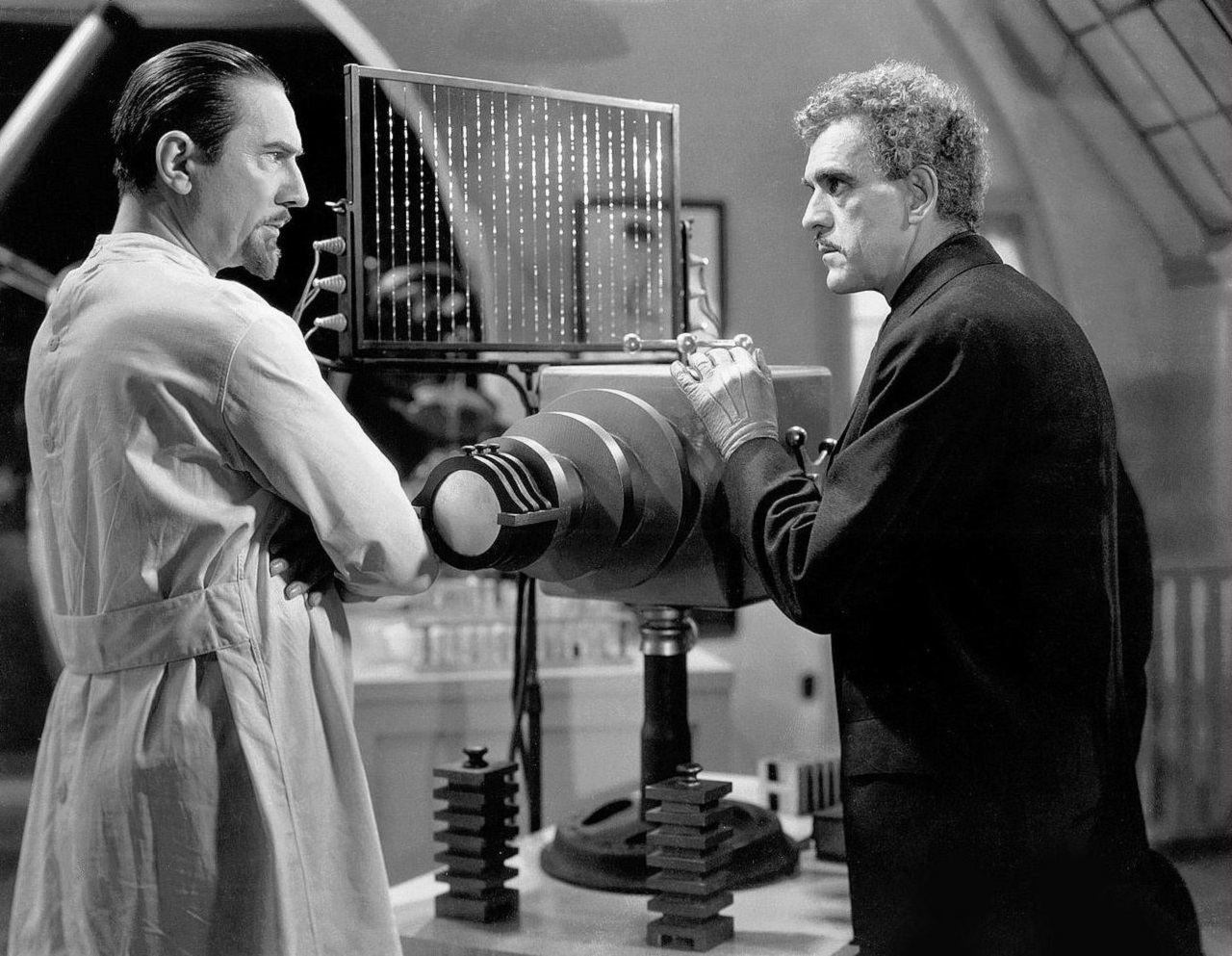

The science in the film comes in constant tones of tremulous awe and religious fear. Boris Karloff conducts his experiments in what is designed more as an alchemist’s chamber than a modern laboratory – a room with high arched ceilings and a dome open to the stars. He also wears a high, angular welder’s mask when conducting his experiments that gives a strange sense of religious ritual to the scene. Typical of this era, the science in the film is nonsensical, where it appeared the idea that any scriptwriter would consult a textbook or get professional advice was anathema. There is the scientifically ludicrous idea at the start of the film of Karloff’s scientist capturing a beam of light from another star and somehow reversing it to look back at the Earth millions of years ago. It feels as though the writer has just learned that it takes light millions of years to get here from another star and tried to incorporate this in a muddled way.

More than anything, you get the impression the idea that drove the film was the employment of radium as a treatment in cancer therapies, which was becoming widespread in real-life in 1935 and saw an industry of quack radium treatments rapidly emerge – and that someone has grafted this onto the standard mad scientist formula. There is another scientifically absurd (if fascinatingly directed) scene where Bela Lugosi uses an ultraviolet camera to photograph Sir Walter’s eye and develops it to find that the last image imprinted there is of Karloff leering in. Elsewhere, the writer is obsessed with strange non-existent powers of the sun with Bela Lugosi getting lines like: “It proves, I think, that human organisms are only part of astro-chemistry controlled by forces from the sun.”

Out of all of this, director Lambert Hillyer does create a film that is undeniably interesting. The strange sense of ritual that surrounds the early scientific experiments sets a fascinating stage for the rest of the film. Hillyer creates a sense of cosmic grandeur during the scene where Karloff scans the stars and we sojourn out into the heavens, following the beam of light to Andromeda. In Africa, there is a particularly captivating scene where Karloff turns the light in his tent out and we see that he is glowing in the dark – and the subsequent scene where he pats his dog, only for it to lie down and die with his glowing handprint on it.

The Invisible Ray‘s main problem is one of story structure – the first half sets up a fascinating, lurid idea of a scientific experiment and its horrific consequences in classic fashion. These are directed in ways that gives the film an unusual atmosphere. However, the second half far less interestingly turns into a more mundane story about a wronged scientist taking revenge on those that have taken credit for his work. Here the film never quite follows through on its great first half.

Lambert Hillyer (1893-1969) was an enormously prolific director – he made more than 150 films from the silent era until his retirement in the 1950s. More than sixty of these were B Westerns. He did venture into genre territory upon a handful of occasions – Before Midnight (1933), a murder mystery with supernatural overtones; Dracula’s Daughter (1936), the first of Universal’s Dracula sequels; and the serial Batman (1943), the first screen adaptation of the DC Comics superhero.