Crew

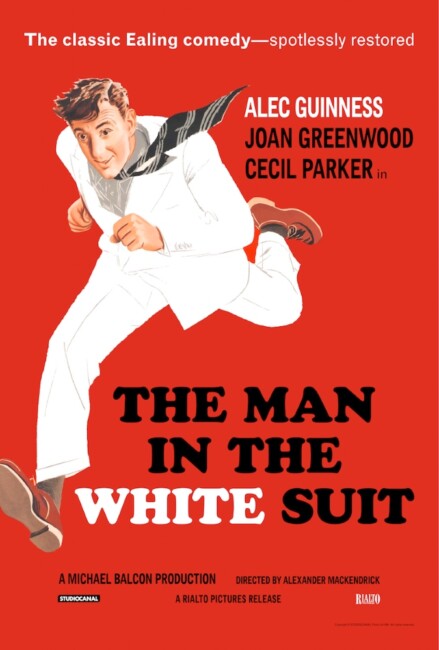

Director – Alexander Mackendrick, Screenplay – Alexander Mackendrick, John Dighton & Roger MacDougall, Based on the Play by Roger MacDougall, Producer – Michael Balcon, Photography (b&w) – Douglas Slocombe, Music – Benjamin Frankel, Music Conductor – Ernest Irving, Special Processes – Geoffrey Dickinson, Makeup – Harry Frampton & Ernest Taylor, Art Direction – Jim Morahan. Production Company – Ealing.

Cast

Alec Guinness (Sidney Stratton), Joan Greenwood (Daphne Birney), Cecil Parker (Alan Birney), Michael Gough (Michael Corlan), Ernest Thesiger (Sir John Kierlaw), Vida Hope (Bertha)

Plot

Sidney Stratton, a cleaner at a Wellsborough textile firm, is fired after it is discovered that he has been conducting unauthorized experiments in the research laboratory. He gets a job at the plant of Alan Birney where he sets about recreating his experiments. He is about to be fired from there too but succeeds in persuading Birney’s daughter Daphne of what he is doing – trying to create a single long molecule that can be spun into a suit that will never wear out and never get dirty. Birney agrees to finance his experiments. However, when Sidney succeeds and news of this non-perishable suit comes out, both the local plant bosses and workers alike try to silence the discovery, fearing an end to business.

The Man in the White Suit was one of the comedies produced by Britain’s legendary Ealing Studios, a company that came to prominence during World War II and flourished in the years immediately following the War. Their most famous comedies were those with Alec Guinness – it was at Ealing that Guinness developed his penchant for playing multiple roles and the films that he appeared in during this time, including the likes of Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), The Ladykillers (1955) and Barnacle Bill (1957), are considered both his and Ealing’s best work.

I must admit that the first time I saw The Man in the White Suit in my teens I did not get it at all. The humour comes so drolly and dryly couched that it completely slipped by. However, on subsequent re-viewing one can see it is a very funny film. There is a good deal of muted slapstick hysteria in the scenes with Alec Guinness trying to get past an officious butler; or the initial experiments with Guinness blowing parts of the building up; and the attempts by a roomful of executives to physically overcome Guinness when he refuses to sign the papers.

The contrast of sober industrial surroundings and the camera opaquely looking on as adults frenetically squabble has a tone that must surely have inspired Stanley Kubrick in Dr Strangelove or, How to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964). Alec Guinness plays through everything with an amusingly aloof certainty, while Joan Greenwood twinkles with an appealing flirtatiousness opposite him.

The Man in the White Suit is interesting in that rather than any usual science-fiction trappings, it concerns itself with sociological science-fiction – specifically the effect a technological discovery might have on contemporary society. The film is interesting for its picture of a heavily industrialized post-War Britain and its cross-section across the Midlands textile boom, taking in the grudging restlessness of the working classes and labour unions and their ultimate cooperation with the mill owners. [In some ways, The Man in the White Suit is a film that is not too far removed from the sociology of Metropolis (1927) – in being centred around heavy industry and the exploitation of the working class by the privileged upper-classes; the system being thrown into chaos when a new technological innovation inspires revolution; and the eventual vanquishing of the discovery and a new resolution of mutual cooperation between the class divide].

The film is certainly commendable, especially amongst the other science-fiction films of the era, in attempting to establish credible-seeming science and chemistry for its discovery. Although the sociology is somewhat naive – Stratton’s discovery is shown as ridiculously idealistic and has to be suppressed for the state of the social status quo, but logical considerations are never brought up such as how the manufacturers could surely protect themselves by exorbitantly hiking the price of the suit or in artificial markets like fashion.

The Man in the White Suit holds allegiance to the mad scientist films of the 1930s and 1940s, in particular their Gothic outlook that scientific discovery brings social chaos and that things are best left the way they are. As one washerwoman somewhat surrealistically comments: “Why can’t you scientists leave things alone? What about my bit of washing when there’s no washing to do?” The film’s eventual decision that the discovery be best kept under wraps for the stability of commerce and the social status quo is no different than in the mad scientist films. The Man in the White Suit merely writes the implicit social conservatism of the mad scientist film across labour divides – the angry union mob is no different to the mobs of villagers with burning torches that storm Frankenstein’s castle. Although here, Alec Guinness’s scientist is not so much mad as merely absent-mindedly oddball. The film ends on an upbeat note showing Alec Guinness walking off undeterred and, it is implied, about to start all over again.