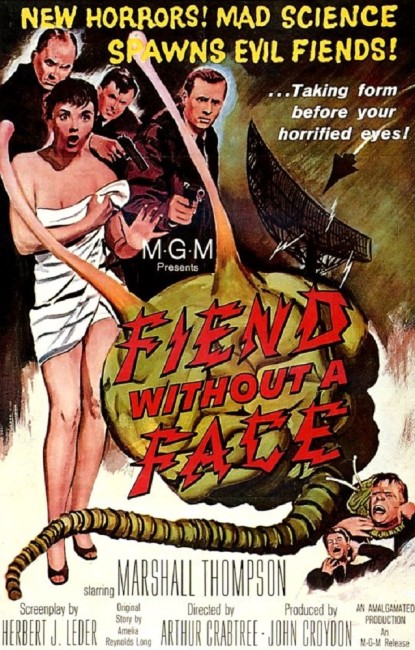

UK. 1958.

Crew

Director – Arthur Crabtree, Screenplay – Herbert J. Leder, Based on the Short Story The Thought Monster by Amelia Reynolds Long, Producer – John Croydon, Photography (b&w) – Lionel Banes, Music – Buxton Orr, Music Conductor – Frederic Lewis, Special Effects – Peter Neilson & Baron von Nordhoff, Makeup – Jim Hydes, Production Design – John Elphick. Production Company – Eros/Amalgamated.

Cast

Marshall Thompson (Major Jeff Cummings), Kim Parker (Barbara Griselle), Kyanaston Reeves (Professor R.E. Wingate), Stanley Maxted (Colonel Butler), Terence Kilburn (Captain Al Chester), Gil Winfield (Dr Warren)

Plot

A number of locals are found dead of unknown causes near a US Air Force base in Winthrop, Manitoba where the military are conducting experiments in long-range radar using atomic reactors. Major Jeff Cummings finds that the victims’ brains and spinal columns have been removed. The investigation leads Cummings to eminent physicist Professor Walgate. Walgate has become wild and babbling and demands that the reactors must be shut down. Cummings discovers that Walgate has been conducting experiments in telekinesis and has succeeded in creating a type of creature that is pure thought. However, the thought creatures, which feed on atomic energy and human brains, have run rampant. As the base shuts the reactor down, the creatures become visible as disembodied brains and besiege a group of people in a farmhouse.

Fiend Without a Face was one of a minor sub-genre of British science-fiction films made during the 1950s. Most of these attempted to pose as American science-fiction films and increase their sales across the Atlantic by importing American stars. Fiend Without a Face even went so far as to pretend to be set in Canada – presumably on the reasoning that Americans being less familiar with Canada would mistake the British locations and the particularly un-Canadian accents of the locals for genuine Canadian locations and figure that was close enough to being an American film.

Fiend Without a Face is very much a product of 1950s science-fiction Cold War paranoia nuttiness – there is its milieu of American-Soviet tension, and it also manages to squeeze in the obsession with the dangers of atomic power. Most fascinating is the amazing strand of anti-intellectualism it manages to crudely symbolise. It may seem fatuous to describe a film about the military shooting down hopping, disembodied brains as the most rigorously anti-intellectual of all science-fiction films but the film cannot help but beg it.

In its own way, Fiend Without a Face is as important in the cinema of American Cold War subtext as Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) and its ilk are. The 1950s were a time when any type of thought that did not conform to very conservative lines was treated suspiciously and intellectuals were thought to be dangerous. Thus it is interesting to watch the progression the film makes wherein disembodied (ie. unrestrained) thought automatically develops a will of its own and becomes evil and monstrous. If one can make the imaginative leap to substitute student radicals for the hopping brains being shot down at the climax then the film becomes appallingly prophetic of the Kent State student riots in the 1960s and what they represented.

Aside from its subtext, there is little that is worth watching in Fiend Without a Face, despite the minor reputation it has – which all rests on the climax. Arthur Crabtree directs in a flat and dreary style, and the film is devoid of any real drama. The budget is evidently very low – the fact that the monsters are invisible for much of the film must have been considered a blessing. The scientific earnestness the film hopes for results in a number of unintentional howlers – a book on Cybernetics spells it ‘Sibonetics’ and a nuclear reactor manages to continue operating, even go into the danger level, despite having its fuel rods removed.

There are only two parts where the film in any way transcends its dreariness. One is the scene of professor Kynaston Reeves in his laboratory trying to trigger telekinesis and finally after much effort being able to turn the page of a book – a sequence that conjures a fervid and obsessive atmosphere among the film’s otherwise drab approach.

The climax is a moment where the film reaches a kitsch lunacy. The truly bizarre image of the military besieged in the house by stop-motion animated brains hopping around on their spinal columns and being shot down in a series of (for then) quite gory b&w meltdown effects reaches a real pulp science-fiction intensity. This sequence even looks forward to Night of the Living Dead (1968) in its own way where the scenes of the brains battering at the boarded windows, even wielding hammers in their spinal columns, manages to capture some of the paranoid siege mentality that George Romero did. These scenes almost make the rest of the film’s dreariness worth sitting through.

The hopping brains later made a reappearance in Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003).

This was one of fourteen films made by British director Arthur Crabtree (1900-75). Most of Crabtree’s other works were non-genre thriller and adventure quote quickies of the 1940s and 50s. His one other genre film was the demented Horrors of the Black Museum (1959).

Trailer here