USA. 2001.

Crew

Director – Iain Softley, Screenplay – Charles Leavitt, Based on the Novel by Gene Brewer, Producers – Lawrence Gordon & Lloyd Levin, Photography – John Mathieson, Music – Ed Shearmur, Visual Effects – Centropolis Effects (Supervisor – Connie Fauser), Special Effects Supervisor – Paul Lombardi, Makeup Effects – Susan Cabral-Ebert, Production Design – John Beard. Production Company – Intermedia Films/Lawrence Gordon Productions.

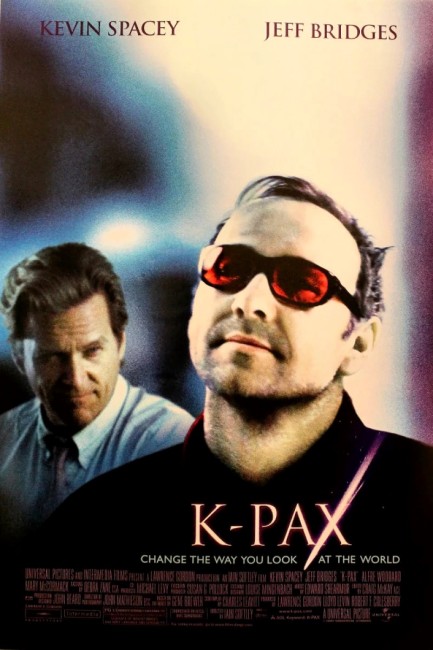

Cast

Jeff Bridges (Dr Mark Powell), Kevin Spacey (Prot), Mary McCormack (Rachel Powell), David Patrick Kelly (Howie), Saul Williams (Ernie), Peter Gerety (Sal), Celia Weston (Doris Archer), Alfre Woodard (Claudia Villars), Kimberly Scott (Joyce Trexler), Conchata Ferrell (Betty McAllister), Brian Howe (Dr Steve Becker), Tracy Vilar (Maria), Melanee Murray (Bess)

Plot

Manhattan psychologist Mark Powell becomes intrigued by the case of a man calling himself Prot who is brought in after being found in Grand Central Station behaving oddly. Prot insists that he is a visitor from the planet K-PAX. Powell becomes intrigued by Prot’s patient rationalism, even more so when Prot provides detailed information about the star system he comes from that only select astronomers could know. Powell is also certain that Prot is of terrestrial origin and is determined to break through his delusion and find the truth.

Upon opening, K-PAX was taken in and celebrated by the people who regard the mawkish, simplistic likes of Forrest Gump (1994), The Cider House Rules (1999) and Chocolat (2000) as profound understandings of the human condition. What was not mentioned in all of this is that K-PAX is blatantly plagiarised from a much superior Argentinean film Man Facing Southeast (1986). The film at least has the excuse of being based on Gene Brewer’s 1995 novel but nowhere in either of the book, Gene Brewer’s four sequels or the film is Man Facing Southeast credited as source of inspiration, when the similarities are such that it is impossible that this could not have been the case.

Man Facing Southeast was a film that was haunting in the crystalline simplicities of its insight into the human condition. It created an amazing allegory for the life of Jesus Christ where the psychologist ended up being cast as Pontius Pilate. K-PAX is Man Facing Southeast having been put through the Hollywood wringer. As part of the faux-liberal desire to offend nobody, the Jesus Christ allegory has been thrown out and in has come bland feelgood messages about believing in one’s self and cliché dichotomies that the simplistic naiveté of fools and idiots has a greater truth to it than does science-based rationalism.

The film also retains the sense of ambiguity that Man Facing Southeast did of leaving us unsure whether the patient is delusional or in fact an alien. Both films sit on the fence between these two mutually incompatible explanations. Of course, without the Christ allegory, K-PAX is much less effective as the parable of faith it was intended as in Man Facing Southeast. K-PAX does offer a slightly more compatible explanation with an end that makes it seem as though it could have been explained as an alien inhabiting another person’s body.

K-PAX was made by British director Iain Softley. If nothing else can be said about Iain Softley, one can at least complement him on the versatility of his genre hopping, with films travelling from Backbeat (1994), a fine biopic about the early days of The Beatles, to the Merchant Ivory-esque Henry James-adaptation The Wings of the Dove (1997) to flops like the wannabe cool computer geek thriller Hackers (1995), the voodoo film The Skeleton Key (2005), the fantasy film Inkheart (2008) and the imprisonment thriller Curve (2015).

K-PAX is a film pitched to the American heartland, a science-fiction film for people who don’t like science-fiction. It is often a beautifully photographed film. Softley and cinematographer John Mathieson insert cool and hauntingly framed shots of light reflected through crystals, the New Mexico desert landscapes, observatory towers against evening skies, the night streets of Manhattan and one gorgeously showoffy shot of the shadows of the red flags on the map moving as dawn rises.

Yet for all Iain Softley’s lovely photography, K-PAX rarely emotionally affects one with the haunting regard that Man Facing Southeast did. There is little of the sense that there was in Man Facing Southeast of the visitor come to heal the sick and the poor in spirit or of the uncanny charisma he exudes. All that Kevin Spacey’s visitor seems to do is incite the patients to squabble over who gets to return home with him at the end – there is not even any accompanying explanation of why the patients come to believe in his particular delusion. All we see is things that cannot help but seem loopy – of him issuing instructions for David Patrick Kelly to find the Blue Bird of Happiness [another uncredited pillaging as this is a creature taken from a fairytale – see The Blue Bird (1940)] or Kevin Spacey talking to a dog.

These are scenes where we are constantly aware of the film nudging us with its desire for affect and to find awe – with only a slightly less accomplished a touch they are scenes that could have been laughed off the screen for their conceptual silliness. The most successful of these scenes is where Kevin Spacey demonstrates the planet’s orbit to a group of assembled astronomers. (If nothing else, the film should be commended for going out and getting its astrophysics and Einstein right. One has the odd minor quibble – why would a visitor from a binary star system (systems that usually do not support orbiting planets by the way) need to wear dark glasses? Would it not be the other way around – that they would find the light on Earth too weak instead of too bright?).

Rarely does the film mount the debate of simplicity vs psychiatry into anything profound, all it has to offer are a series of glib, pithy tradeoffs between Kevin Spacey and Jeff Bridges. When Spacey departs at the end, the film leaves us with little more than a handful of feelgood cliches – “psychiatry doesn’t have all the answers to the human condition”, “that we should make the best of the here and now as it is the only life we have.”

Kevin Spacey’s performance was highly acclaimed and even spoken of by some people at the time as award worthy. One cannot help but feel that Spacey is miscast. Spacey is an actor whose specialty seems to be anonymous tightly bound white-collar types on the verge of meltdown or eruption of one type or another. Nobody delivers witheringly dry sarcasm like Kevin Spacey does. On the other hand, he is not the first actor that comes to mind when you think of a character delivering hauntingly simple reflections on the oddities and contradictions of the human condition or radiating patient, understanding charisma. When Spacey starts delivering Prot’s lines with the same arch tone that usually denotes the way he delivers a snide putdown, you realise this is not an actor who’s acting but someone who is merely holding himself in check. Jeff Bridges, who himself gave a much better performance in a similar role in Starman (1984), is more modestly convincing as the psychologist, although this is clearly a feelgood movie psychologist who blurs the lines of involvement with his patients much more than professional decorum would allow in the real world.

(Nominee for Best Cinematography at this site’s Best of 2001 Awards).

Trailer here