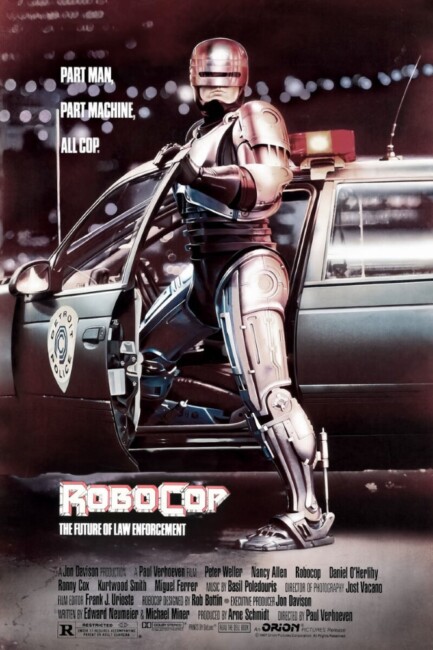

USA. 1987.

Crew

Director – Paul Verhoeven, Screenplay – Michael Miner & Ed Neumeier, Producer – Arne Schmidt, Photography – Jost Vocano, Music – Basil Pouledoris, Photographic Effects – Peter Kuran, Stop Motion Animation – Phil Tippett, Special Effects Supervisor – Dale Martin, Makeup Effects – Rob Bottin & Stephen DuPuis, Production Design – William Sandell, RoboCop Design – Craig Davies & Peter Ronzani. Production Company – Tobor Pictures.

Cast

Peter Weller (Alex Murphy/RoboCop), Nancy Allen (Ann Lewis), Kurtwood Smith (Clarence Boddecker), Miguel Ferrer (Robert Morton), Ronny Cox (Dick Jones), Dan O’Herlihy (The Old Man), Paul McCrane (Emil), Robert DoQui (Sergeant Reed)

Plot

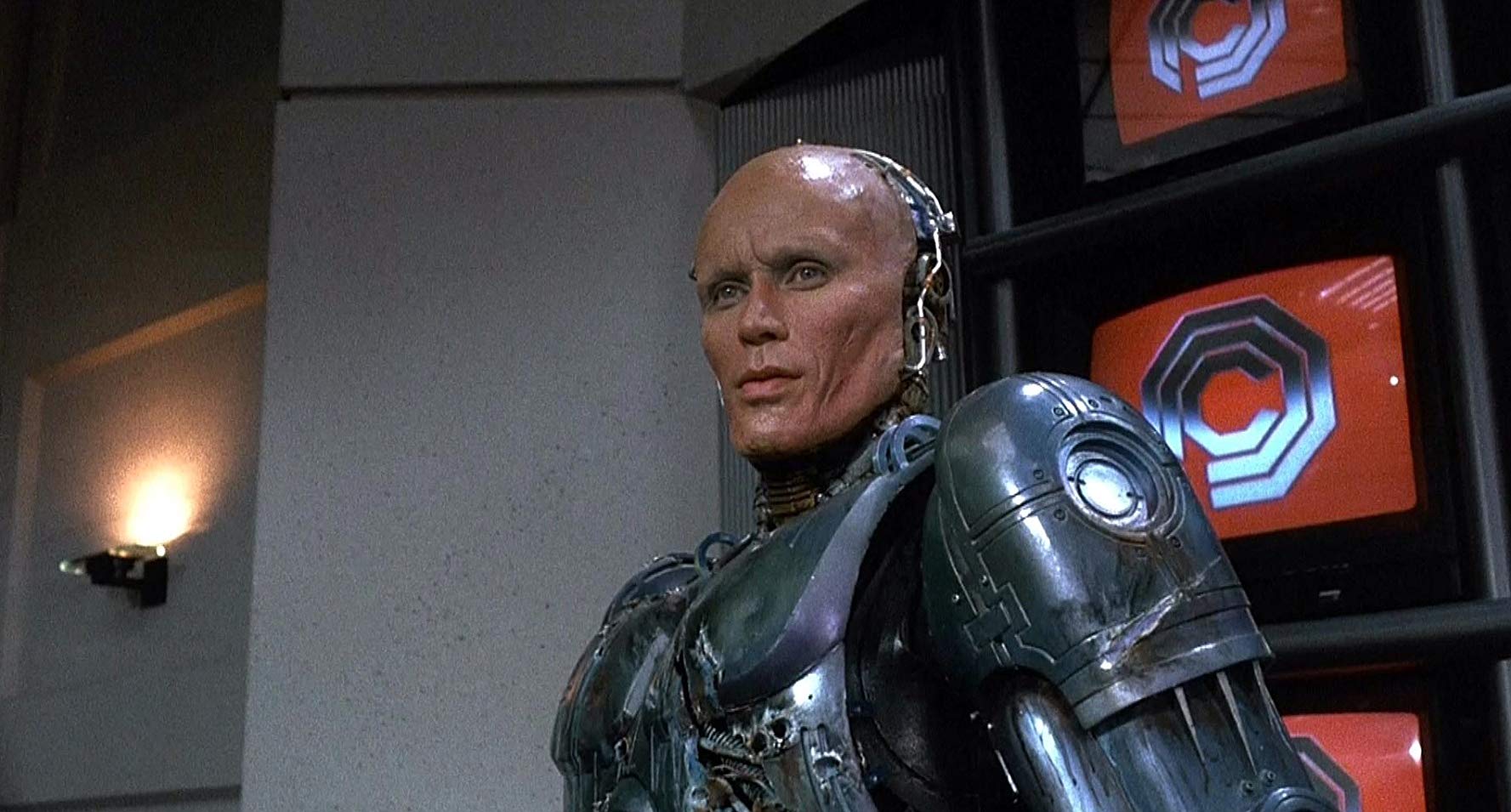

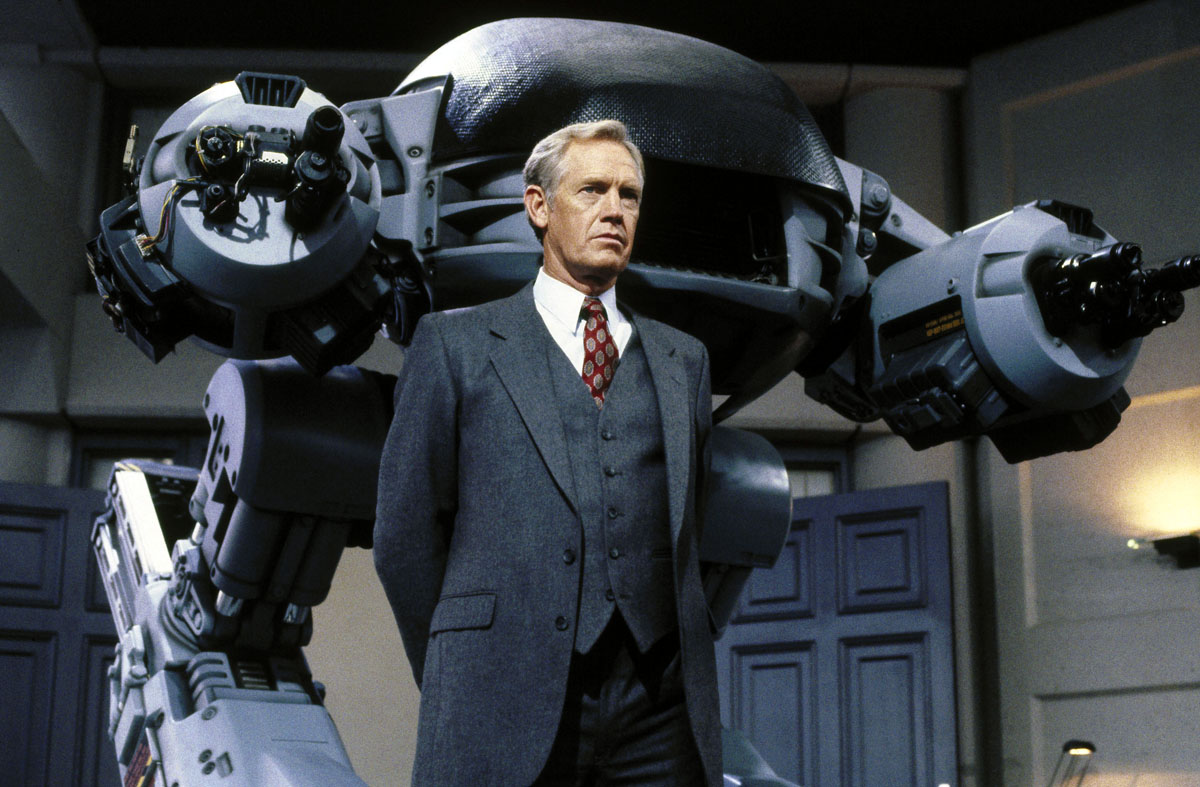

Detroit of the near future where Omni Consumer Products Corporation now runs the police force as a private enterprise operation. OCP is seeking tougher and more efficient ways of enforcing the law and is considering the idea of a heavily armed enforcement robot. Officer Alex Murphy arrives at a new precinct posting where he is partnered with Ann Lewis. On their first day out on patrol, they stumble into a shootout with drug dealers. The drug dealers sadistically blow Murphy’s arms and legs off with shotguns and leave him for dead. A hotshot OCP executive then claims ownership of Murphy’s body, has his memory wiped and the body rebuilt with armouring, data inputs and a computer in his head, to be unveiled as ‘RoboCop’, the OCP’s vision of the future of law enforcement.

RoboCop was a sleeper success when it came out. Made on a modest $13 million budget, it proved a sizeable international hit. RoboCop became regarded as a modern genre classic and during the subsequent decade the theme of the cyborg cop became one of the most prominent in sf/action films. There were three sequels and several tv spinoffs (see below). The great surprise was how RoboCop, being perceived as both a science-fiction and an action film, ended up attracting some excellent reviews from most critics at the time it came out. The surprise about this is what a violent film RoboCop actually is and how this seemed to either be overlooked or excused (something that almost all of director Paul Verhoeven’s subsequent films have been heavily lambasted for). What did endear RoboCop to people was the strong sarcastic bite the film came with that gave it the appearance of an ultra-violent action movie with a socially acute, even intellectual edge.

On a level beyond the obvious comic-bookish sf/action one, RoboCop is a pungent satire of Reaganite America. In an era when the term ‘corporate raider’, ‘hostile takeover’ and the phrase “greed is good” became buzzwords, Reagan (and across the Atlantic, Margaret Thatcher) heralded a great era of wealth. The price of this was in drastically curtailing government spending, which included the shipping out to private enterprise of many state social services – amid this, the idea of a private enterprise-run police force seemed the next logical extension (indeed, shortly after the film came out, the era saw the introduction of private enterprise prison systems in the US). This also saw the slashing of funding for many state-provided services to the underprivileged and disenfranchised including health, welfare and social services. This resulted in a massive increase in crime, something that the Reagan establishment responded to with a muscular crackdown on law and order. The era also saw the rise of the phoney War on Drugs, while around this time Reagan had also authorised the sale of military surplus weaponry to lae enforcement agencies, leading to the rise of heavily armed urban SWT teams.

On cinema screens, the two quintessential crosscuts of Reaganite America were provided by Michael Moore’s Roger & Me (1989), a biting documentary about the savage human cost of corporate restructuring, and Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987) about the ruthless amorality of the corporate raider ethos. In fact, Wall Street has many similarities to RoboCop – RoboCop could almost be seen as a crosshatch between Wall Street‘s corporate raider expose and Stone’s later Natural Born Killers (1994), where he tried to satirically confront media-eroticised violence by piling on a numbing excess of ultra-violence.

RoboCop, with its satiric vision of corporate amorality, private-enterprise police and neo-fascistic appeals to crime crackdown, sharply sinks its teeth into the underside of Reaganite America. The film is infused with a considerable sense of black humour – particularly about the media, from the satiric commercials for nuclear war scenario videogames and Reagan’s Star Wars defence initiative, to Leeza Gibbons, then the co-host of tv’s bland, almost entirely content-free entertainment show Entertainment This Week, cast (one suspects, not entirely with her own awareness of the satiric intent) as an empty-headed tv newsreader. (In interviews, Paul Verhoeven spoke of how the idea came to him when he had just arrived in Hollywood and the bizarreness of sitting in a hotel room watching the 1986 Challenger space shuttle disaster on tv, only to see it being interrupted every few minutes by commercials for used-car salesmen and the like). It was this combination of an action movie that offered a blackly funny view of 1980s corporate ethos, media numbing and a satiric escalation of the violence and neo-fascistic underpinnings of action movie heroes that gave RoboCop an intellectual justification that appealed to many at the time.

On the other hand, you can ask if RoboCop is a satire at all. Is the film a satire on action movie ultra-violence, or is it, seen in the larger perspective of Paul Verhoeven’s career, more a fortuitous case of coincidence between a savvy script and a director who is indulging his penchant for excess? The Dutch-born Paul Verhoeven first appeared on cinema screens with Who Is It (1971), a film based on the memoirs of a real-life Amsterdam prostitute, which marked Verhoeven’s frequent subsequent interest in upfront sexual (and violent) material. Verhoeven made various other films in the Netherlands – Turkish Delight (1973), which concerned the many loves of an artist (played by Rutger Hauer in his first film role); Keetje Tippel (1975), another film about prostitution; the critically acclaimed war film Soldier of Orange (1977); Spetters (1980) about the lives of dirtbike racers in a nowhere town; and the interestingly strange and hilariously blasphemous The Fourth Man (1983). Verhoeven began to show his penchant for over-the-top excess with his first English-language success, the entertainingly ultra-violent mediaeval romp Flesh and Blood (1985).

The success of Flesh and Blood led to Paul Verhoeven netting the assignment of RoboCop. Paul Verhoeven’s proclivities became more apparent in subsequent mainstream American films such as Total Recall (1990), Basic Instinct (1992), Showgirls (1995), Starship Troopers (1997) and Hollow Man (2000). These tend to disappear under a desire upon Paul Verhoeven’s part to bombard his audience with an overkill of sex and violence. Verhoeven eventually revealed himself as being a trash movie director who delights in serving his audience a mass of excesses. Sometimes there is a sarcastic sense of black humour run through it all – both Total Recall and Starship Troopers feature the same satiric snippets from commercials and tv news soundbites playing in the background as RoboCop. On the other hand, when the script is not attuned to Paul Verhoeven’s predilections, as was the case with Total Recall, which wasn’t a mindless action film at all, or Starship Troopers – the films only end up a jumble of directorial sadism. You sense that Verhoeven constantly seeks justification for serving up the things he does – only he could make the extraordinarily trashy Showgirls, which some consider one of the worst films of the 1990s, and straight-facedly conduct it as a film about one woman’s struggle not to be sexually exploited.

Nominally, RoboCop takes up the theme of struggle of the human to emerge from inside the machine, and the film became a template for a number of subsequent films on the subject. Here Peter Weller gives a fine performance in the part of a human struggling to regain his identity. It is debatable however if Paul Verhoeven has any concerns for the machine-entrapped Weller. For one, he spends next-to-no time giving us any portrait of Murphy as an ordinary human before he undergoes cyborgisation for us to contrast Robocop to. To the contrary, Paul Verhoeven’s emphasis in RoboCop is not the emergence of Murphy’s humanity but the almost comic-bookish scenes of Robocop in action and the cuts back to the corporate chicanery, which are granted far more time than Murphy’s suffering. You cannot help but wonder – does Paul Verhoeven care about Murphy’s humanity? The scene where Peter Weller is murdered by shotgun surgery is shocking. However, after the umpteenth scene where we are served up toxic waste meltings, bullets to the head and perpetrators thrown headfirst through plate-glass windows, the shock brutality of the earlier scenes is buried under a mountain of overkill. You do ever so slightly get the impression that Paul Verhoeven enjoys the comic-bookish ultra-violence of it all.

Moreover, the overriding tone in these scenes, and the various others where Robocop goes into action, is one of sarcasm. It might be useful to compare RoboCop to any other action film – say an Arnold Schwarzenegger comic-book from around the same era such as Commando (1985), Raw Deal (1986) or Predator (1987) where Arnie is cast as an almost superhuman hero, wades in amid much comic-bookish ultra-violence and despatches people while making atrocious puns, or even to compare RoboCop to fantasies of libertarian law enforcement such as Dirty Harry (1971) or the Sylvester Stallone masterpiece Cobra (1986). [Although, the real source for RoboCop, one suspects, is the British comic-strip Judge Dredd (1977– ) about an emotionless cop engaged in satirically righter-than-right law enforcement in a near-future US, which was badly filmed as Judge Dredd (1995)]. All of these are comic-book films; so too is RoboCop, yet here the moral catharsis of Dirty Harry blowing away scumbags that deserved it or the cocky superhmanism of Arnie triumphing has been replaced by a gallows humour where the blowing away of scumbags is treated as a big black joke.

The truth about Paul Verhoeven, one suspects, is that he doesn’t like people very much. Not many of the central characters in Paul Verhoeven’s films are particularly likable as people – he invests little to no effort in our empathy with them, while there is little warmth and certainly no sentimentalism in a Paul Verhoeven film. Most of the character arcs of the heroes/heroines in Verhoeven’s films are defined simply by their learning to toughen up in a world of hard and brutal edges. Verhoeven piles on violence and excess in his films but it frequently feels like something that is there for its own sake and indifferent to the people present. The sum effect often feels like directorial sadism being randomly applied to innocent people, for no particular reason other than that the director in question is trying to work out some sadistic urges of his own. Total Recall offers mass destruction applied against innocent bystanders; RoboCop and Starship Troopers find violence against others a gloating joke and invites audiences to laugh at it; both Basic Instinct and Hollow Man invite us to participate in rape fantasies; while in Showgirls you are not entirely sure if the film is asking us to feel anger about or voyeuristically enjoy Elizabeth Berkeley’s humiliations by an exploitative stripper industry. Through it all, you feel there is a director who has a cynical contempt for humanity – there are few other filmmakers whose heroes and heroines must undergo such a battering and brutalisation before achieving their catharsis; while anybody cast as a bystander along the way seems like dogmeat. The more you look at Paul Verhoeven’s films, the more you feel that the satiric edge you see in RoboCop is less savvy political bite than merely Paul Verhoeven exercising his contempt at Reaganite America.

RoboCop has been cited, justly so, as one of the major cinematic Cyberpunk texts. It is perhaps worth contrasting literary and cinematic Cyberpunk. Like the work of literary Cyperpunks, such as William Gibson, Bruce Sterling and Neal Stephenson, RoboCop sees the future as one dominated by a dense outgrowth of Reaganite America – governed by monolithic corporations that have grown more powerful than governments; the encroachment of the then-new personal computer revolution and the intrusion of cyber technology into people’s lives in new ways that blur the lines between the real and virtual and the machine and human; and the seeming new social divide between a rich, corporate elite and the poor and criminal with no middle-class in between any more.

Cinematic science-fiction has been willing to embrace literary Cyberpunk and borrow its trappings – Blade Runner (1982) even predates William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer (1984), which became the seminal Cyberpunk text. However, bar occasional exceptions, literary and screen Cyberpunk have trodden widely differing paths. While almost all literary Cyberpunk is concerned with the intrusion of the 1980s computer revolution into people’s lives and in examining the society of the future, cinematic Cyberpunk seems stuck down at the theme of the human struggling to find their identity against the intrusion of the machine. All cinematic Cyberpunk films with few exceptions have this central man-vs-machine battle at the base – from Blade Runner through Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and The Matrix (1999). The difference is best illuminated by looking at the almost entirely opposed political agendas of both – Gibson et al’s heroes are loner hackers who live outside the system and are frequently anarchists attacking the established corporate system; RoboCop and other filmed Cyberpunk fantasies such as tv’s Superforce (1990-1), Freejack (1992), Nemesis (1993), Virtuosity (1995) and tv’s Total Recall 2070 (1999) have appropriated Cyberpunk agendas for kickass action scenarios. They are neo-fascistic fantasies of future law enforcement whose heroes are muscular, often cyborg-enhanced cops, blowing away scumbags and defending the corporate-dominated status quo of the future.

There were two film sequels to RoboCop:– the usually vilified RoboCop 2 (1990), which is in many ways a more interesting film than the original, and the anodyne RoboCop 3 (1993). Paul Verhoeven bowed out after the first film. Peter Weller appears in the RoboCop 2 but was replaced by Robert Burke in the third film. Nancy Allen appears in all three films. RoboCop (2014) was a cinematic remake of the original starring Joel Kinnaman. RoboCop was later expanded into a disappointingly poor tv series RoboCop (1994-5) starring Richard Eden in the title role, which only lasted 23 episodes. RoboCop: Prime Directives (2000) was a six-hour tv mini-series sequel, starring Page Fletcher. There were also several animated tv spinoffs of the films – RoboCop (1988-9), which lasted for twelve episodes, and RoboCop: Alpha Commando (1998-9), which lasted for 40 episodes. The irony of pitching such a gratuitously violent film as RoboCop down to animated children’s audiences seems to have escaped the tv executives – indeed, in all the tv versions, Robocop is prevented from being able to shoot suspects as he regularly does in the films. Be Kind Rewind (2008) offers up an amusing amateur remake of RoboCop.