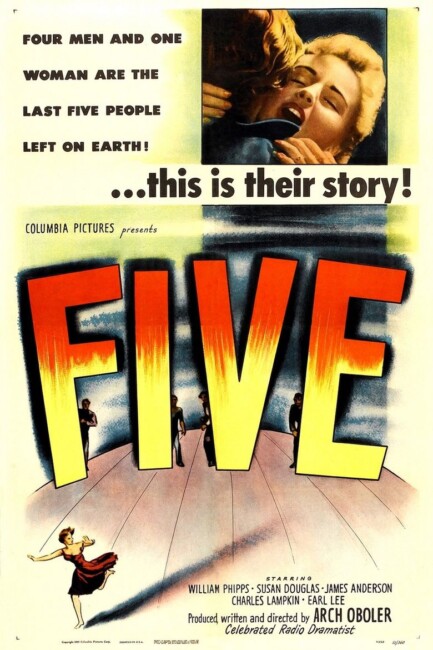

USA. 1951.

Crew

Director/Screenplay/Producer/Production Design – Arch Oboler, Photography (b&w) – Sidney Lubow, Ed Spiegel, Louis Clyde Stoumen & Arthur L. Swerdloff, Music – Henry Russell, Cliff House Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Production Company – Lobo Productions.

Cast

Susan Douglas (Roseanne Rogers), William Phipps (Michael Rogan), James Anderson (Eric), Charles Lampkin (Charles), Earl Lee (Oliver P. Barnstaple)

Plot

The world has been devastated by nuclear war. Pregnant housewife Roseanne Rogers has survived because she was in a lead-lined x-ray room when the blast hit. She stumbles through the ruins until she comes to a clifftop house inhabited by Michael Rogan. He welcomes her in. They are later joined by bank manager Oliver P. Barnstaple and his assistant, the African-American Charles, who survived because they were in a vault, although Oliver dies not long after. They also drag the German Eric out of the surf where he explains that he survived because he was on an expedition climbing Mount Everest. Tensions grow within the group as Michael and Eric argue over Eric’s wanting to return to the city where supplies are plentiful against Michael’s desire to stay in safety and cultivate their own food. Tensions are further heightened by Eric’s racial views and dislike of Charles and of both he and Michael competing for the attentions of Roseanne.

Five has the distinction of being science-fiction cinema’s very first nuclear war film. Coming a mere six years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it was the first cinematic work to address the nightmare the world had suddenly woken up to about what had happened.

Director/writer Arch Oboler was very much concerned about the possibilities of surviving an all-out attack and the tensions that would emerge in the aftermath. Films dealing with nuclear war subsequent to Five however were less interested in the human dramas than he was and treatments quickly entered the realm of pulp B-movies. Captive Woman (1952) came along set in a future world where society had been reduced to rubble and invented the post-holocaust drama on screen. Far more popular at the time was The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), which introduced the idea of the atomically revived dinosaur where the creature in question became a metaphor-loaded menace that ran rampant creating wholesale destruction.

A couple of years after that Roger Corman stole much of the plot of Five in one of his first directorial films, the cheap Day the World Ended (1955), where his single ingenious spin was the addition of a mutant creature to the mix. And that fairly much was the serious treatment of nuclear war themes for the decade. It was not until the very end of the decade and into the 1960s in efforts such as On the Beach (1959), Dr Strangelove or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), Fail-Safe (1964) and The War Game (1965), most of which were notedly made after the Cuban Missile Crisis, that filmmakers began to again address nuclear war away from the arena of B movies and in terms of grimly real possibilities.

Arch Oboler came to filmmaking after an acclaimed background in radio. As a result, much of Five tends to come across as essentially being ‘radio with pictures’. Talk dominates the show rather than action. Characters have a tendency to turn their heads towards the sky and philosophise, while on the soundtrack the score goes into a full sweep of violins. The first half-hour is very slow moving, although the film picks up not long after that with the introduction of James Anderson’s character whereupon tensions start to emerge.

Despite the film’s talk-driven focus, an occasional lyricism emerges – where Charles Lampkin dances without music on the terrace because the pregnant Susan Douglas cannot stand up to join him; a scene where the characters nostalgically reminisce over the sounds and smells that they miss; where Susan Douglas finally kisses William Phipps but then in the midst of embrace mistakenly calls him “Stephen.” One of the film’s more lyrical stretches is the recitation of African-American poet James Weldon Johnson’s poem The Creation (1919), which pays tribute to the magnificence of creation, while framed against natural shots of the landscape.

At the same time, Arch Oboler also tends to heavy-handed message-making. There is the habit of seeing much of what has happened in terms of Biblical imagery (as was the case with other end of the world films of the era), like having a placard sitting in the ruins warning that we need to repent of our sins (an image that was also used in On the Beach). It is a film where you see that Arch Oboler earnestly hopes that the obliteration of all civilisation will lead to an Edenic renewal – the film ends on the Biblical quotation ‘Behold a New World’. Alas, the optimistic upsurge the film ends on – the entire human race killed, the baby dead, everyone else in the party killed, but at least the couple together to carry on the species seems absurd in its assumption of cheer in the circumstances.

As with the later nuclear war drama The World, The Flesh and the Devil (1958), one of Arch Oboler’s predominant interests is the issue of racial tolerance. For this express reason, we have an African-American character (Charles Lampkin) as part of the titular quintet. James Anderson’s clipped Teutonic manner and the clear implication that he shares sympathy with Nazi racial views perhaps over-obviates the opposing side of the issue.

Despite Arch Oboler’s desire to make a parable about the need for racial tolerance, there is still a subtle underlying racism (or perhaps patronising racial attitudes) to the film. Charles Lampkin’s character is portrayed as placid and untroubled, not even offended when Anderson starts using racial language. He is a happy and unopiniated character who is only ever seen in a socially inferior position – as assistant to Earl Lee’s bank manager or happily helping out tilling the fields. Today, for example, it would be impossible to write a similar character that would not get played with his own voice and demonstrate a sense of anger when people start to derogate his position.

The other subtle racism that goes on is how he, even though being the other male present, is regarded as neutered and it never considered that he would have any sexual interest in Susan Douglas as the other men do. He is also killed off by the end so as to in effect allow the white male and white female free to go off and repopulate the world anew. The World, The Flesh and the Devil attempted to redress this but its solution was the even more absurd notion of the woman entering into a post-holocaust interracial menage a trois.

The depiction of nuclear war is scientifically unfeasible. In fairness, not much was known by the general public about the effects of a nuclear explosion and radiation fallout at the time (and what was known was still classified by the US Department of Defense). The opening scene of the film takes place some way away from the blast radius, yet we also see buildings shredded and bodies reduced to skeletons. Heroine Susan Douglas manages rather incredulously to have survived by being inside a lead-lined x-ray cubicle in the midst of the blast zone at the time – something that immediately makes you think of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) and its famous survival of a nuclear detonation via lead-lined refrigerator.

The journey back to visit Los Angeles at the end is laughably underwhelming (at least watching it after more than half-a-century of post-holocaust films). After a supposed ground zero bomb blast, all we get is one street where the cars have been abandoned askew with a few skeletons lying about and air raid sirens still blaring, not even any ruined buildings. Most of the scenes are shot from a vehicle prowling through the streets with the camera pointed up (clear evidence of a low budget and Arch Oboler not having permission to block off several streets for filming). Even so, the tameness of this vision in comparison to the devastation at Hiroshima is absurd. One supposes that you cannot be too hard on Five, given that it was the first of its kind. Screen depictions of nuclear war that would follow in films such as On the Beach, The War Game, Barefoot Gen (1983), Testament (1983), When the Wind Blows (1986), Letters from a Dead Man (1986) and The Divide (2011) are overwhelmingly unanimous in the bleakness of their outlook.

Perhaps one of the more unusual aspects of the film is the location where it takes place – Arch Oboler’s own home in Malibu, a cliffside house that was designed by the famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright. It makes for an unusual location on the eye, even if you suspect that a production designer would have created something that was more open to filming.

Arch Oboler (1909-87) gained a considerable name for his work on radio, beginning as producer/writer/principal creative force on the famous horror anthology series Lights Out (1934-57). Oboler then began to expand out onto film, beginning with the script for the thriller Escape (1940). He made his directorial debut with Strange Holiday (1945) wherein a man returns from a holiday to find the US overtaken by a Nazi government. Oboler made a total of seven films as director, most of which fall over into genre territory. These include:- the split personality film Bewitched (1945); The Twonky (1953) about a tv set that comes to life; and the alien invasion film The Bubble (1966). Perhaps the most influential of Oboler’s films in retrospect was the hit African adventure Bwana Devil (1952), which was the first feature film to be made in 3D.

Trailer here