aka Stairway to Heaven

Crew

Directors/Screenplay/Producers – Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, Photography (colour + b&w) – Jack Cardiff, Music – Alan Gray, Music Conductor – Walter Goehr, Special Effects – Henry Harris, Technicolor Limited & Douglas Woolsey, Additional Visual Effects – Percy Day, Makeup – George Blackler, Production Design – Alfred Junge. Production Company – The Archers.

Cast

David Niven (Squadron Leader Peter Carter), Kim Hunter (June), Roger Livesy (Dr Frank Reeves), Marius Goring (Conductor 71), Robert Cooke (Flight Officer Bob Trubshaw), Raymond Massey (Abraham Farlan), Joan Maude (Chief Recorder), Abraham Sofaer (The Judge), Kathleen Byron (An Angel)

Plot

May 2nd, 1945. Squadron Leader Peter Carter’s bomber has been shot up while returning from a mission over Germany and is aflame. Carter contacts June, a young American radio operator in England, and briefly speaks to her. He then tells her that he is going to jump from the plane rather than be burned alive, even though he has no parachute. Carter somehow survives the jump unhurt and lands not far from the town where June lives. They meet and fall into one another’s arms. The rest of Carter’s crew arrive up in Heaven. When Carter fails to do so, the heavenly authorities realise that a mistake has been made – Carter became lost in the fog and missed being brought up. A heavenly envoy is sent to retrieve Carter but Carter refuses to leave June. A heavenly trial is convened to examine Carter’s reasons for wanting to stay on Earth. Meanwhile, with all his talk of the afterlife, June takes Carter to neurologist Dr Frank Reeves, who determines that Carter is experiencing delusions as a result of brain damage and must be operated on immediately. Up in Heaven, as the trial begins, the opposing side brings out the most Anglophobic prosecutor they can find who is determined to try Carter for no less than being British.

Michael Powell and his producer, sometimes co-director Emeric Pressburger, was one of the most celebrated of post-War British directors. Powell had been directing since 1928 but first came to attention as one of the co-directors on the problem-ridden The Thief of Bagdad (1940) and then went onto make classics like The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), A Canterbury Tale (1944), Black Narcissus (1947), The Red Shoes (1948), The Tales of Hoffmann (1951) and Peeping Tom (1960), among many others. All of Powell’s films of the 1940s were fabulous Technicolor fantasies that made full and gorgeously extravagant use of the new medium of colour in a time when most films were still being made in black-and-white. They were fantasies made to transport British audiences away from the mundanity of The Wartime Blitz and post-War economic shortages. A Matter of Life and Death is one of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s most highly regarded films. (See bottom of page for Michael Powell’s other films).

During the Wartime era, Powell made a number of patriotic films, including The Lion Has Wings (1939), The Spy in Black (1939), Contraband (1940), 49th Parallel (1941), One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942) and The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. With A Matter of Life and Death, Powell and Pressburger set out to create their own version of the afterlife fantasies that became the vogue in Hollywood during the Wartime era. A Matter of Life and Death is really a British equivalent of the American-made Air Force angelic fantasy A Guy Named Joe (1943). The plot reads as a distillation of elements from the most popular of the Hollywood afterlife fantasies of the era – the afterlife bureaucratic mix-up and complications that ensue in taking/not taking a person up when their time had come from Here Comes Mr Jordan (1941); the afterlife for pilots who are shot down in combat from A Guy Named Joe; and the heavenly trial convened to argue for and against someone’s soul from All That Money Can Buy/The Devil and Daniel Webster (1941).

The plot is contrived. The neurological explanation of David Niven’s hallucinations offered up by Roger Livesy is not at all convincing, especially Livesy’s dubious claim that the condition will be cured by everybody playing along with Niven’s delusions. There are also obvious contortions of the plot that have to be conducted in order to set Roger Livesy up as David Niven’s advocate. The last quarter of the film goes off at a tangent into a bizarre debate as to the superiority of British vs American cultures. Nevertheless, the trial scenes are mounted with an epic dramatic flourish. There is a shattering sacrificial ending, even if the film subsequently offers a cheat that gets out of it.

Less so than the story, A Matter of Life and Death is worth watching simply for the lavishness of the colour and architecture with which Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger are determined to dazzle us. Like Wim Wenders in Wings of Desire (1987) several decades later, Powell and Pressburger depict the afterlife in black-and-white and the corporeal world in colour. (“One is starved for Technicolor up there,” Marius Goring’s awfully gay afterlife agent comments upon arriving on Earth).

A Matter of Life and Death has possibly one of the most epic openings ever created for a film (which may have been inspired by the start of the Rite of Spring sequence in Disney’s Fantasia (1940) a couple of years earlier). The camera opens in a sweep across the entire universe, moving past stars and giving us a quick astronomy lesson, passing a nova and wondering if maybe the inhabitants there “had an accident with the uranium atom,” and eventually coming down to Earth, closing in on Europe where one city is alight with flames and then drifting across to a fog-covered England, before it segues into the main action. (This was all conducted before the era of CGI effects and digital 3D animation and the sequence is all the more stunning as a result).

Even after such an awe-sized opening, Powell and Pressburger don’t stop there – the opening scene immediately captivates our attention with David Niven as the last man in a burning plane getting radio operator Kim Hunter on the other end and telling her how he is planning to jump from his plane without a parachute rather than face being burned alive. The romance that occurs between them in these few minutes is fabulous, with Kim Hunter’s plain beauty framed against gorgeous red background lighting that seems to suggest the imminent flames that are about to engulf David Niven.

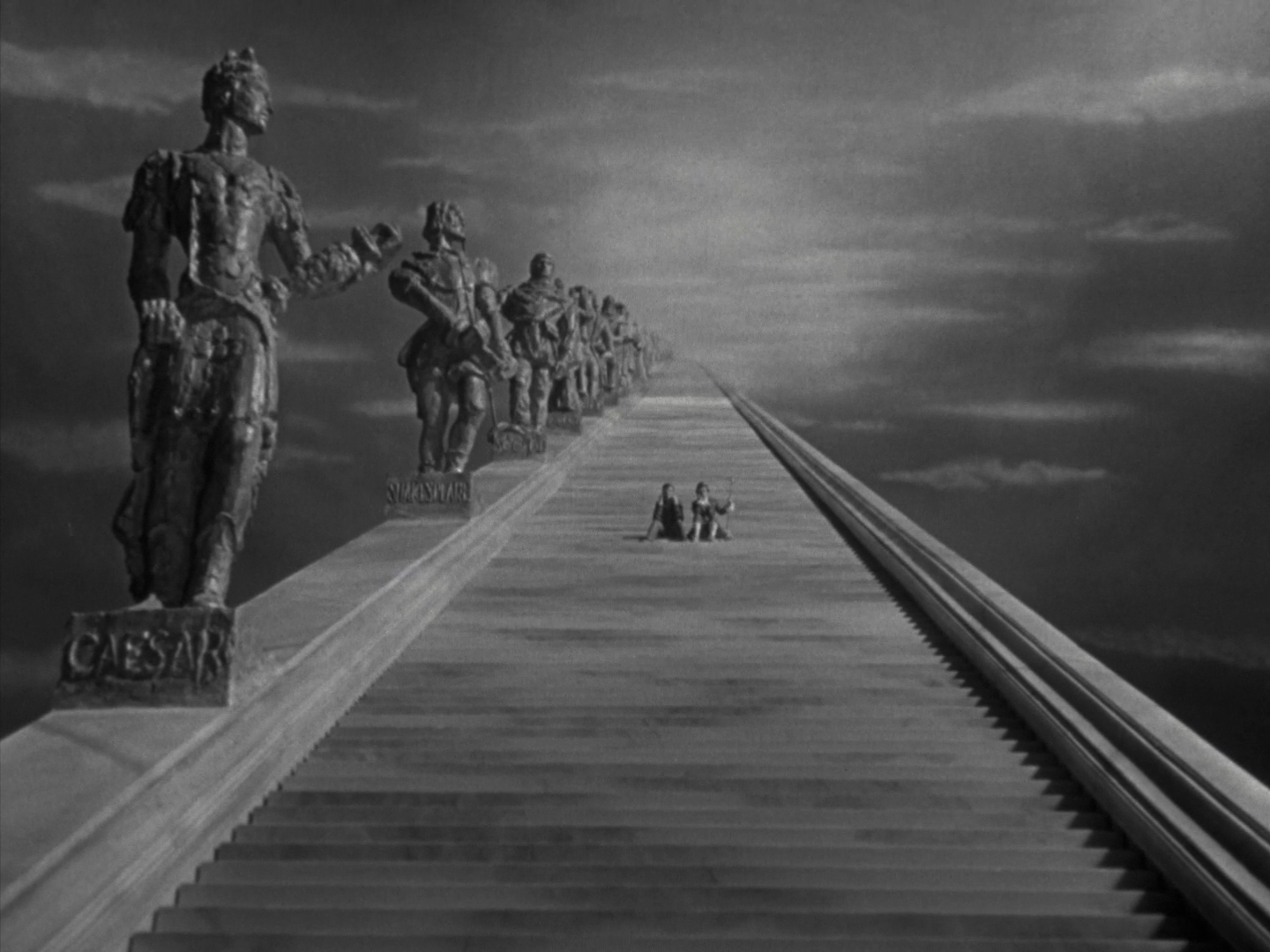

The visions and architecture that Powell and Pressburger depict throughout are utterly stunning – absolutely no other film of this era being made in Hollywood was conducted on such an epical scale. Most other Hollywood afterlife fantasies, for instance, simply depicted the afterlife as a nebulous realm of white clouds. Instead, Powell and Pressburger are determined to overwhelm us architecturally and throw in visions of David Niven and Marius Goring seated on a giant marble escalator that travels all the way up to infinity, lined with statues of famous people or pilots moving up the escalator while carrying their wings; the vision of a massive dome filled with clouds where the camera pans all the way down to see hundreds of tiny arrivals appearing through the huge arched doors; a library of records that is rendered in staggering size, all seen through immense circular holes in the floor of the afterlife anteroom; of the courtroom as a gigantic amphitheatre, which the camera pulls back to reveal nestled in a horseshoe valley with the rest of the galaxy surrounding it, and with the escalator stretching down from the courtroom into the operating room where David Niven is under anaesthetic.

Powell and Pressburger even delight in purely visual touches like looking down upon a village through a camera obscura, or of a conversation held in front of the players in a game of ping pong who have been stilled in motion. A Matter of Life and Death is a film that is made with a love of all the possibilities that the new Technicolor process could offer and succeeds wonderfully. There are few films that can be enjoyed purely for the extravagance of the visuals they offer.

Michael Powell’s other films of genre note are:– The Phantom Light (1935), a little-seen comedy-thriller set in a supposedly haunted lighthouse; as co-director of The Thief of Bagdad (1940); the ballet fantasy The Red Shoes (1948); the ballet fantasy portmanteau The Tales of Hoffmann (1951); the classic psycho film Peeping Tom (1960); and the children’s film The Boy Who Turned Yellow (1972). Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger (2024) was a documentary about Powell and Pressburger.

Trailer here