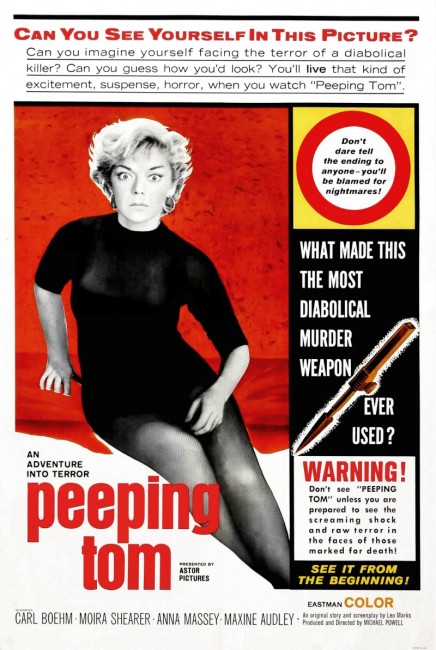

aka The Face of Fear

UK. 1960.

Crew

Director/Producer – Michael Powell, Screenplay – Leo Marks, Photography – Otto Heller, Music – Brian Easdale, Art Direction – Arthur Lawson. Production Company – Michael Powell (Theatre) Ltd.

Cast

Carl Boehm (Mark Lewis), Anna Massey (Helen Stephens), Maxine Audley (Mrs Stephens), Moira Shearer (Vivian), Jack Watson (Inspector Gregg), Pamela Green (Milly), Shirley Ann Field (Pauline Shields), Brenda Bruce (Dora), [uncredited] Nigel Davenport (Sergeant Miller)

Plot

Mark Lewis works as focus puller for a film studio while also moonlighting as a nudie photographer. He carries a 16mm film camera wherever he goes and likes to film women in a state of fear as he kills them using a blade hidden in the camera’s tripod leg. Afterwards, he obsessively watches the films in his flat. A loner, he befriends Helen Stephens, the girl in the apartment beneath his, and they go on a date. He plays films for her that show how his psychologist father used him as the subject in a series of experiments in fear. However, when he leaves the body of his latest victim in a trunk on the studio soundstage, this brings police attention towards him.

Michael Powell (1905-90) was one of the great British directors. During World War II and in the decade after, Powell, and his producer, sometimes co-director Emeric Pressburger, made an amazing series of Technicolor dramas that included the likes of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), A Canterbury Tale (1944), A Matter of Life and Death/Stairway to Heaven (1946), Black Narcissus (1947) and the ballet fantasies The Red Shoes (1948) and The Tales of Hoffman (1951). These were extravagant works made in rich colour in a period when most films were still being made in black-and-white. A number of these fall into the fantasy genre (see below for a full list of Michael Powell’s other genre films).

Peeping Tom is a classic film no doubting, although few thought so at the time of its release. The British press savaged the film and it was not successful in release, not being seen in the US until 1962. Indeed, the universally vehement critical reaction given to the film effectively torpedoed the career of Michael Powell, who was then riding on a career high. Powell subsequently made The Queen’s Guards (1961) in the UK but then departed for Australia to make two films there and dabbled in television, only returning to the UK to make the children’s film The Boy Who Turned Yellow (1972) before his death in 1990.

In its initial theatrical release, several scenes were cut from Peeping Tom, including depictions of nudity and greater detail of the murders, even scenes where the police discuss the killings. Some of these scenes have been restored today – the very brief shot of a bare breast as Pamela Green relaxes in bed; a scene where Carl Boehm stands waiting in the corner store as his boss is seen selling a customer some nudie pictures; the police discussions – although the rest of the cut material is believed lost. The film languished forgotten until Martin Scorsese, who saw it in the 1960s, arranged and promoted its re-release in 1978. It has since become a cult film and there has been a quest to restore a complete cut.

Peeping Tom makes for a study in compulsive psychology. The psychology itself rings unlikely but the way that Michael Powell maps the compulsions into symbolism and behaviour is fascinating. Camera symbols pop up in just about every part of the film. The movie camera becomes almost an extensive organ of Carl Boehm’s – he is constantly extending its tripod (not unlike a rather obvious phallic symbol) as he goes to kill his victims. When he doesn’t have the camera, he is framing pictures with his hands; threatened, he clutches the camera to him in a foetal position and at the end immolates himself on its tripod. Even the shots of him peering into the window of the downstairs flat seem to frame him in a lens crosshairs.

This is a film where Michael Powell asks an uncomfortable series of questions about how complicit the filmmaker is in what it is he stages for us. Not to mention the question that hangs over the whole film of exactly what sort of conflicted sexuality the director is working out on screen by having desirable women posing and then showing them being killed.

Like Hitchcock in Psycho (1960), which premiered two months later the same year, Powell delves headlong into the issue of voyeurism – both films sit in what would have been an uncomfortably seedy place for audiences of the day – Anthony Perkins looking through peepholes at girls showering, Carl Boehm photographing nude models here. Both films also seem to come from a place that associates strong sexual desire with guilt and cross over into a disturbed headspace that sees the natural response being to kill the object of desire.

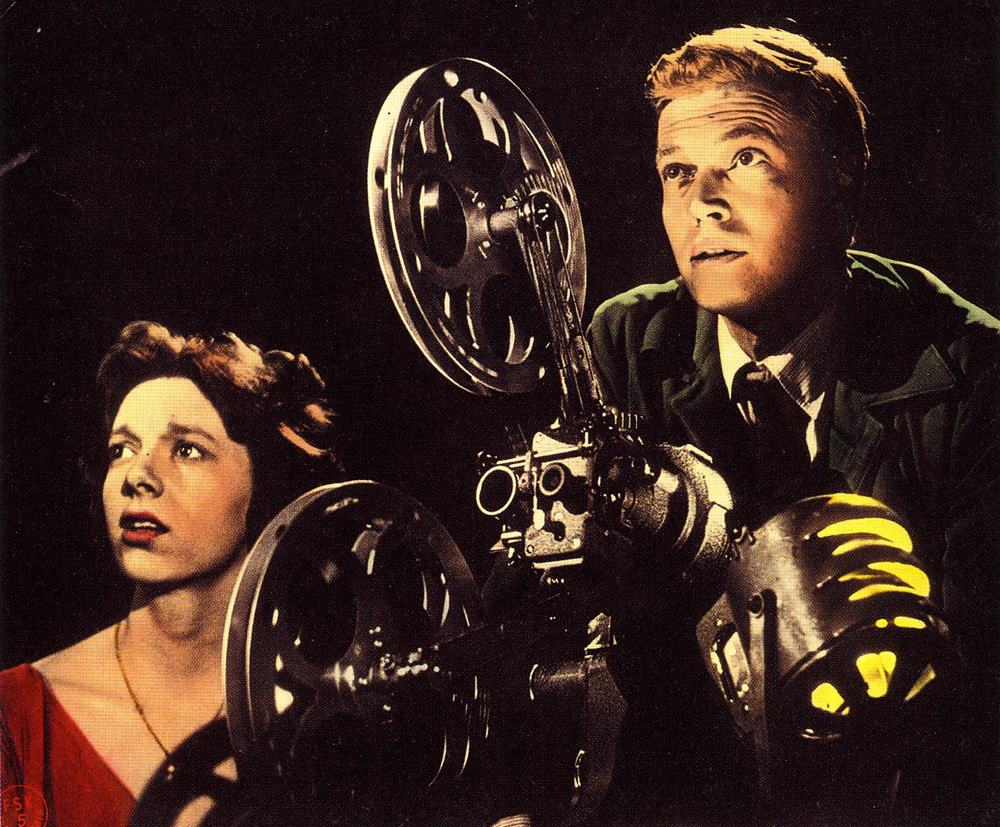

In effect, Carl Boehm and his camera become a stand-in for Michael Powell himself. No scene seems more telling than the one where Carl Boehm has Moira Shearer (notedly also the star of Powell’s ballet films) on the soundstage set where she warms up by doing a dazzling series ballet twirls as he fusses about the boring technical business of arranging the props, the lighting, measuring the proper focal length – in other words, the director cast as the technician determined to create the perfect cinematographic set-up (Powell himself) and the unreachably beautiful woman capering freely, before the two merge in the brutal quenching of that object of desire.

Michael Powell’s films are known for their richness of cinematography and extraordinary use of colour (especially in their being made at a time when movies were still predominantly being made in black-and-white). The modern dvd restoration of Peeping Tom makes the film’s colours look astonishingly fresh all over again and allows us to see the way in which Powell lit his sets, something we seem to have lost with the death of 35mm film stock.

You could also argue that Powell makes the first ever Found Footage film in a handful of scenes where his camera becomes the handheld one that Carl Boehm wields as he stalks victims. In 1960, we had not had the Slasher Film either and so the idea where the camera takes the killer’s point-of-view was also a unique one.

The cast are a very odd bag – clipped Teutonic-accented Carl Boehm is miscast in what really should be a role for a British public-school type but he does what he can in his blank way. Better is a young Anna Massey, an actress more known for her roles in British tv dramas in mid-life. Many of Massey’s scenes are stolen by Maxine Audley as her uncannily alert blind mother. In another piece of symbolism, Powell himself, as well as his wife Frankie and son Columba, play Carl Boehm’s father, mother and younger self in the home movies he screens for Anna Massey.

Michael Powell’s other films of genre note are:– The Phantom Light (1935), a little-seen comedy-thriller set in a supposedly haunted lighthouse; as co-director of The Thief of Bagdad (1940); the afterlife fantasy A Matter of Life and Death/Stairway to Heaven (1946); the ballet fantasies The Red Shoes (1948) and The Tales of Hoffmann (1951); and the children’s film The Boy Who Turned Yellow (1972). Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger (2024) was a documentary about Powell and Pressburger.

Trailer here