UK. 1940.

Crew

Directors – Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell & Tim Whelan, Screenplay – Miles Malleson, Scenario – Lajos Biro Producer – Alexander Korda, Photography – Georges Perinal, Music – Miklos Rosza, Special Effects Director – Lawrence Butler, Production Design – Vincent Korda. Production Company – Alexander Korda Films Inc.

Cast

Sabu (Abu), John Justin (Prince Ahmed), June Duprez (Princess), Conrad Veidt (Grand Vizier Jaffar), Rex Ingram (Genii), Miles Malleson (Sultan)

Plot

A blind beggar is found in the Bagdad marketplace. He is taken to the harem where he tells his story. The beggar claims that he is Ahmed, the prince of Bagdad. He tells how, upon the advice of his vizier Jaffer, he went out into the marketplace in disguise to see what his people thought of him – only to be double-crossed by Jaffer who had him arrested and thrown into jail, saying he was mad for claiming to be the prince. Aided by the mischievous thief Abu, Ahmed managed to escape. In Basra, he fell in love with a beautiful princess. Trying to win her hand, he ended up crossing the path of Jaffer who also desired to woo the princess. In retaliation, Jaffer magically blinded Ahmed and turned Abu into a dog. Now, Ahmed is taken before the princess who has fallen into a sleep from which only he can wake her. She begs him to deliver her from betrothal to Jaffer. And so Ahmed and Abu set forth on a magical quest to find the means of destroying Jaffer and winning the princess’s hand.

The Arabian Nights fantasy has often emerged very tattily in its various screen incarnations – look at B budget efforts such as Aladdin and His Lamp (1952), Siren of Baghdad (1953), Son of Sinbad (1955), The Wizard of Baghdad (1960), Captain Sindbad (1963) and Arabian Adventure (1979) or swashbuckling Hollywood mainstream adventures that dropped the fantasy elements like Arabian Nights (1942), Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1944), A Thousand and One Nights (1945) and Sinbad the Sailor (1947), even a number of comedies. It is rare that anybody seems to have the budget to conduct the Arabian Nights fantasy well on screen. (For a more detailed listing of other films see Arabian Nights Fantasy).

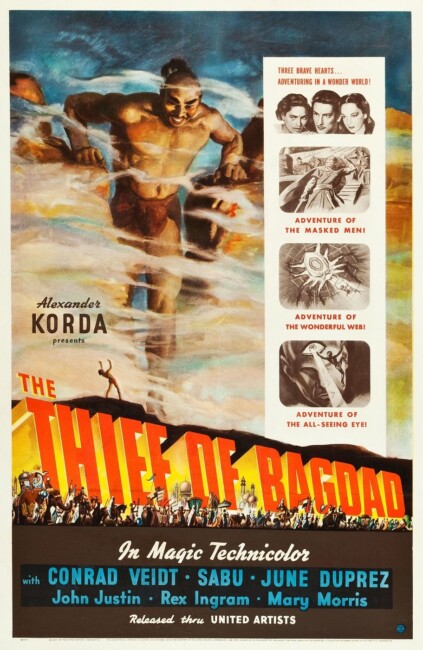

This classic 1940 production of The Thief of Bagdad was one such occasion that they did. Certainly, the original Douglas Fairbanks version of the story The Thief of Bagdad (1924) had flown with the same wondrous flight of fantasy (and is the superior film of the two) but this version was an equally resplendent production. It was a production that sang out in Technicolor splendour in a period when colour was not widespread and offered some of the most amazing special effects spectacle of its age.

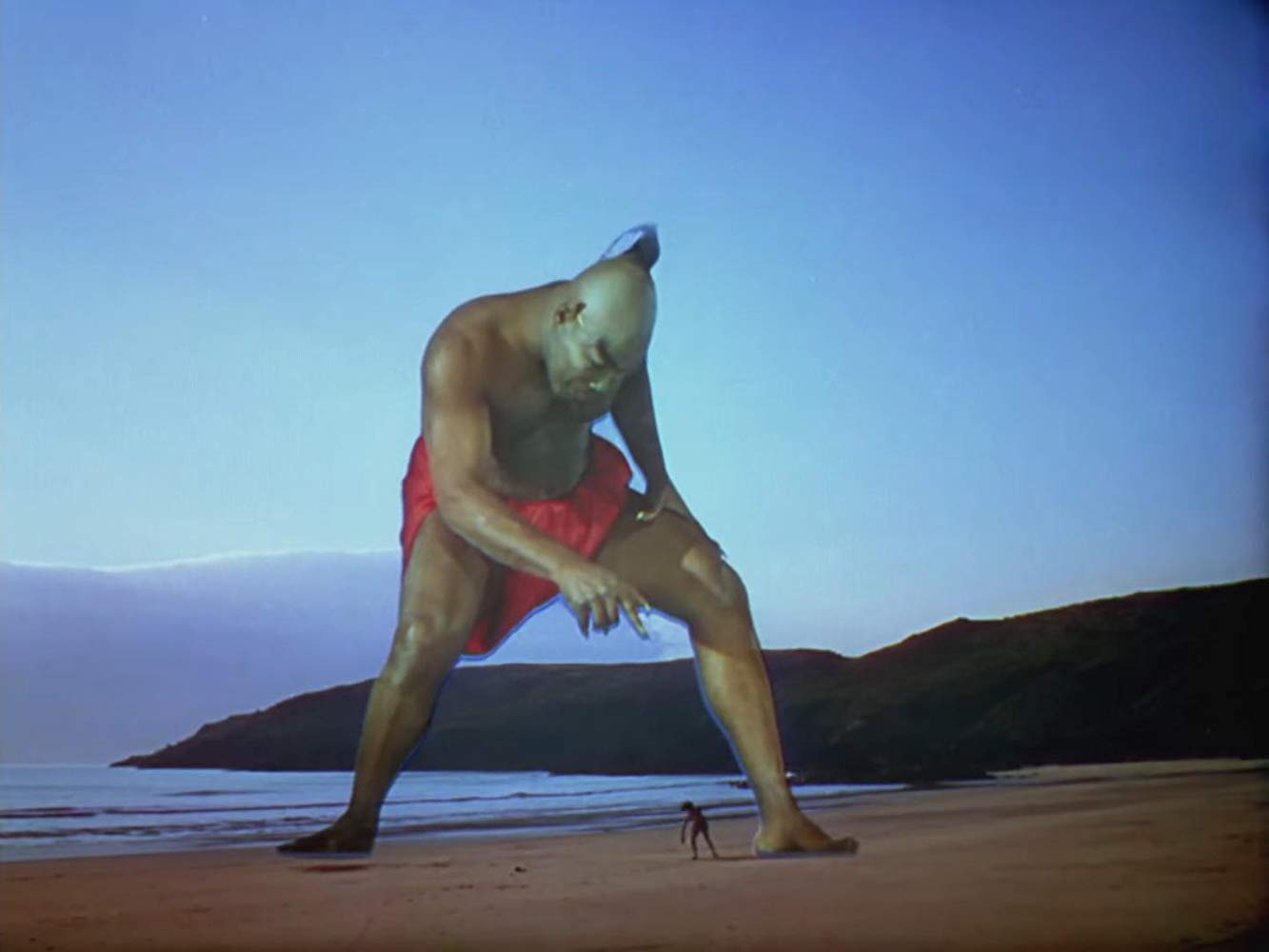

You could say that The Thief of Bagdad was the Star Wars (1977) of its day. It was certainly rare up until Star Wars and the modern fantasy era for cinema to unfurl its wings with such a splendid full-flown fantasy – the only other films to come anywhere near such over the next three-and-a-half decades were Ray Harryhausen’s duo of Sinbad films The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973).

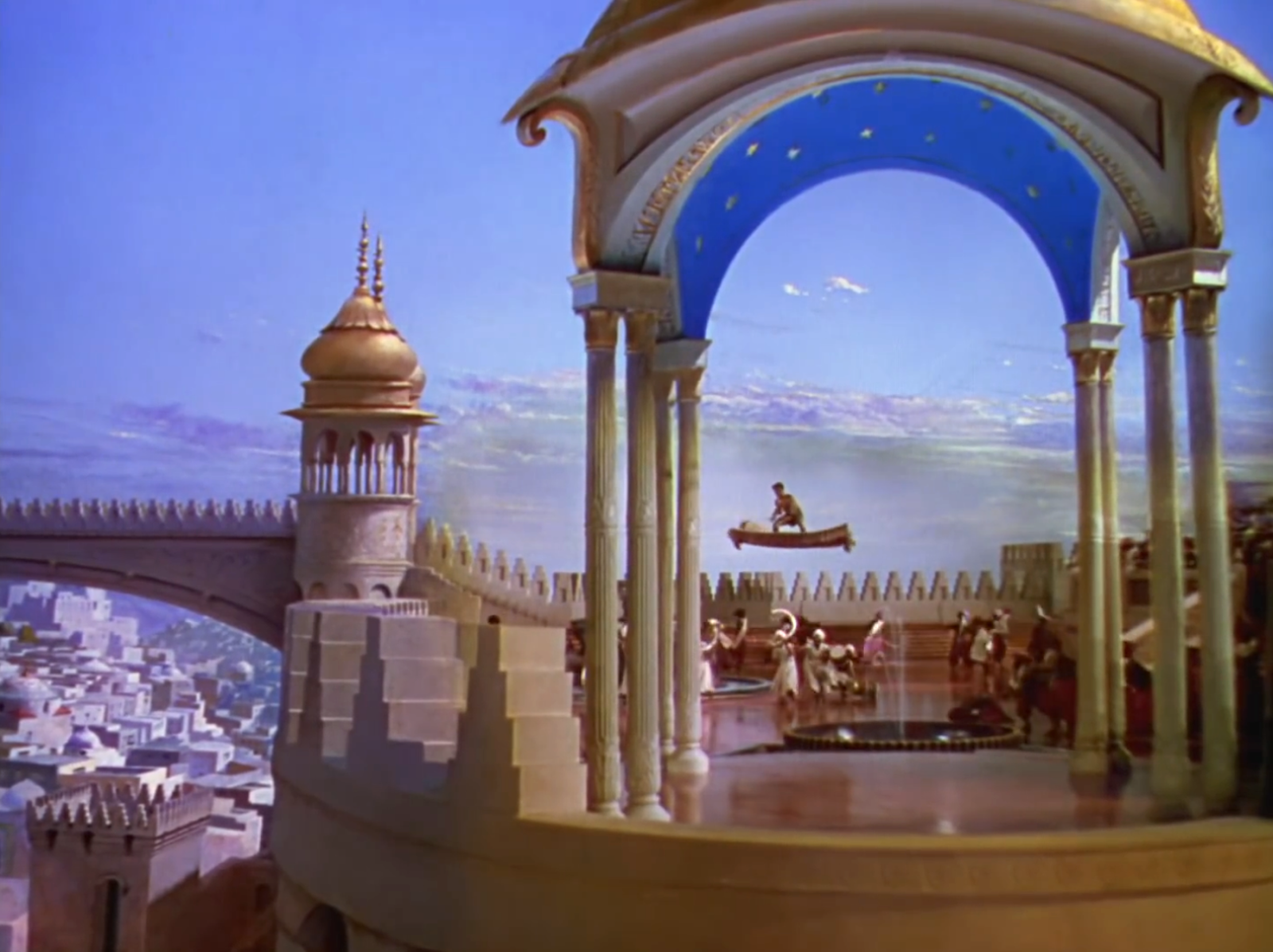

The Thief of Bagdad offered up a peerless blend of screen-fantasy spectacle and pure-hearted romance. An extraordinary sumptuousness has been lavished on the film – from the richness of the costumes and sets to parades of elephants to the film being shot in rich Technicolor at a time when most films were being shot predominantly in black-and-white. There are some sensational set-pieces – Sabu’s battle with a giant spider as it crawls across its three-hundred foot diameter web, his journey through the air holding onto the pigtail of the genii, not to mention flying carpets rides, swordfights and full-rigged sailing ships.

The sets are stunning – from the huge set of stairs that Sabu is chased up and down to the temple with a 300-foot tall statue, the spider’s gigantic web, the exquisite palace gardens and a beautifully detailed series of marketplaces. The effects could perhaps have benefitted from the hindsight of today’s motion control cameras – the flight of the wind-up magic horse and the genie are flat and dimensionless but the beautiful matte and superbly detailed model work elsewhere still catches the breath.

Producer Alexander Korda clearly tailored The Thief of Bagdad for the presence of Sabu, the Indian-born teenager who first came to fame in Korda’s Elephant Boy (1937) and went onto appear in several other Korda productions, including Jungle Book (1942). Sabu has a boyish sprightliness and, while he is not a great actor, still manages to communicate an enormous degree of exuberance on screen. Although, it should be noted that the boyish and mischievous Thief that Sabu plays is very different to the masculine romantic figure that Douglas Fairbanks was in the 1924 Thief of Bagdad. In fact, this version of the film splits the Fairbanks role in two – with the young Sabu inheriting the thief half, and the romantic element being carried by the impossibly handsome John Justin.

The romantic scenes are slightly offset by some dreary songs. However, John Justin and the flat June Duprez give a larger-than-life fairytale romance to their scenes together. The script provides them with wonderfully overwrought dialogue:

“Where’ve you come from?” she asks as he sneaks into her private garden.

“From the other side of time to find you.”

“How long have you been searching?”

“Since time began.”

“Now that you’ve found me, how long will you stay?”

“Till the end of time.”

Rex Ingram also steals a number of scenes as the jovial and often sinister genie.

The Thief of Bagdad was beset by some colossal production problems, including three directors, three scriptwriters and as many of either again uncredited (with purportedly Alexander Korda and his brother Vincent, as well as William Cameron Menzies, director of the Korda’s Things to Come (1936), also stepping in to direct various scenes) and all apparently at war with the other. Not to mention the entire production being uprooted and moved from England to Hollywood after the outbreak of World War II. It is amazing that the film went anywhere at all in such circumstances, let alone to become one that is so unitedly spectacular.

The other versions of the story are:– the classic silent The Thief of Bagdad (1924) with Douglas Fairbanks, the cheap Italian-made The Thief of Baghdad (1961) with Steve Reeves, and the even cheaper tv-made The Thief of Baghdad (1978) with Kabir Bedi.

One of the co-directors of the film was Michael Powell. Michael Powell went onto become one of the most celebrated directors of the post-War era in Britain with films like The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and Black Narcissus (1947). A number of Michael Powell’s other films also fall into genre classification, including the afterlife fantasy A Matter of Life and Death/Stairway to Heaven (1946), the ballet fantasies The Red Shoes (1948) and The Tales of Hoffmann (1951), the psycho film Peeping Tom (1960) and the children’s film The Boy Who Turned Yellow (1972). Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger (2024) was a documentary about Powell and Pressburger.

The Thief of Bagdad was made by the famous Hungarian producer Alexander Korda, one of the movie moguls of the 1930s and 40s. Korda produced a number of other fantasy works during the era, including the light fantasy comedy The Ghost Goes West (1935), his adaptation of Jungle Book (1942), and two collaborations with H.G. Wells, Things to Come (1936) and The Man Who Could Work Miracles (1937).

Trailer here