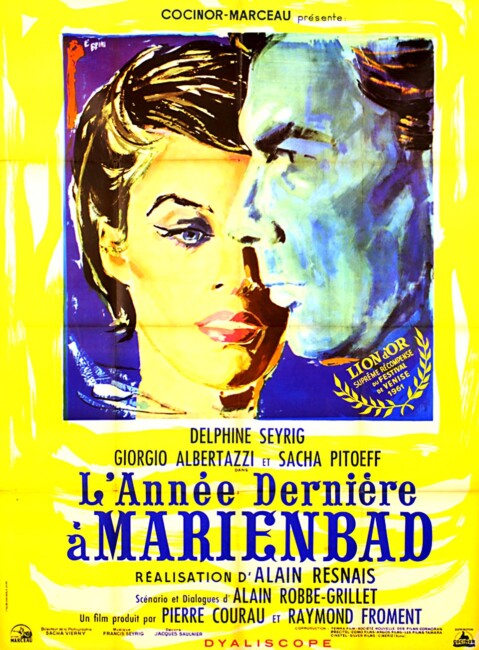

(L’Annee Dernier a Marienbad)

France. 1961.

Crew

Director – Alain Resnais, Screenplay – Alain Robbe-Grillet, Producers – Pierre Coureaux & Raymond Froment, Photogaphy (b&w) – Sacha Vierny, Music – Francis Seyrig, Art Direction – Jacques Saulnier. Production Company – Colinor

Cast

Giorgio Albertazzi (X), Delphine Seyrig (A), Sacha Pitoeff (M)

Plot

People drift through a large, ornate French hotel. Sometimes time freezes. X thinks he met A last year in the garden at Fredericksburg, although she is unable to remember him. He himself is not even certain whether it was at Fredericksburg, Marienbad, Baden-Salsa where they met or here. He describes how when they met she nearly gave herself to him but held herself back at the last minute. They agreed they would meet again in one year’s time to see if his love for her was strong enough to wait or if she would have forgotten him. He presses her not to hold back this time and to remember what happened.

The French New Wave of the 1950s and 60s is regarded by many critics as one of the greatest artistic heights ever achieved in cinema. The films of the New Wave also have a prominent pseudo-intellectualism that persistently frustrates. They come packed with often random surrealistic imagery, political and philosophical monologuing, and an almost total disregard to any form of straightforward narrative. Typical of the pseudo-intellectual game-playing in these films is a scene in Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus (1950) where the world’s greatest book of poetry is opened and revealed to be filled entirely with blank pages. In their favour, these films do occasionally achieve moments of great visual poetry.

Unlike Hollywood cinema, the French New Wave was formed out of the French post-War art movement. Its proponents were artists, poets and Marxists rather than filmmakers. The French New Wave is unrelated, but not dissimilar to, science-fiction’s New Wave – both share a common desire to shatter mainstream conventions. The French New Wave took an especial delight in breaking traditional conventions of narrative and in taking film, traditionally a realm of objective depiction, into increasingly subjective arenas.

Last Year in Marienbad was probably the most influential film of the New Wave after Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960). Although undeniably influenced by Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950), its shifting, existential view of memory (and possibly time itself) is one of the New Wave’s most important themes. Time and memory are subjects that preoccupy director Alain Resnais who has returned to the theme again and again, from Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) through Je T’aime, Je T’aime (1968), which explored the basic ideas of Marienbad in more overtly science-fictional terms. Alain Resnais’s English-language film Providence (1977) blended fantasy and reality in what it became apparent was the imagination of an aging writer. In Smoking/No Smoking (1993), Resnais was the first director to explores the current theme of alternate outcomes (see Sliding Doors [1998]) of events – in this case depending on whether a character chooses to smoke a cigarette or not.

Last Year in Marienbad baffles with its commercial defiance. Its narrative is non-linear, its compositions static, its mysteries are enigmatic and completely unanswered. However, it was highly influential. It broke cinema away from the idea of straight clear-cut dramatic narrative. Last Year in Marienbad‘s influence can be felt in open-ended mystery films like Blow Up (1966) and The Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975). Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) could almost be Last Year in Marienbad as a horror film. Even a tv series like Sapphire & Steel (1979-82) models itself on Marienbad‘s temporal disjunctions – indeed, watching Last Year in Marienbad one almost expects David McCallum and Joanna Lumley to step in and set things right at any moment. Marienbad is also echoed in films like Harry Kumel’s Daughters of Darkness (1971), which also starred Delphine Seyrig as a vampire woman haunting another echoingly oppressive hotel, and the experimental The Decay of Fiction (2002).

The film opens in a series of slow camera movements that drink in the sumptuousness of the ornately carved dome ceilings, the cherubim pelmeting, the walls of gilted mirror paneling, the lengthy corridors. Later we move out into the elaborate formal gardens, which look like a Cubist checkerboard made up of geometric lines of conical hedges and perfectly arranged but lifelessly frozen lawns and lakes. Giorgio Albertazzi’s voice accompanies the tour, describing the beauty of the place but this turns into a loop of endless repetition.

Finally the camera comes to the people of the place for the first time. They all stand frozen as the camera pans about the tableaux, then momentarily move and freeze back into position again. Alain Resnais maintains these striking frozen tableaux throughout – of people standing frozen at a bar with the only movement a waiter picking up a broken glass, or still tableaux through which figures move in the foreground. The effect is of achingly opulent beauty yet of meaningless sterility, of a people of privilege caught in endless repetition of movements that are poses and mean nothing.

There is a nominal plot to Last Year in Marienbad but even that has an incredible unfocused vagueness to it. A man and a woman meet in the grounds of a hotel. He thinks he met her last year in a hotel at Fredericksburg, or it could have been at Marienbad or Baden-Salsa, he isn’t sure. She is unable to remember him. He describes the holiday, how she seemed to be drawing him on and decided to give herself to him but at the last minute changed her mind and walked away. She has a memory of him in her room but cannot remember anything else. Throughout he begs her to accept his love this time.

What is going on is a complete mystery but that is the very fascination of the film. There appear to be temporal flips – skillfully maintained by having characters turn from one shot to complete the move in different clothes and a different year in the next shot. Always the film maintains a baffling enigma – is the character of Sasha Pitoeff meant to be Delphine Seyrig’s husband? her lover? or what?

Throughout Alain Resnais emphasises the nature of memory. Last Year in Marienbad is, if anything, a cinematic attempt to affect the casual atemporality of human memory – its ability to freeze events and randomly flip back through time. Always Resnais emphasises the subjectiveness of memory. The details that Giorgio Albertazzi describes to Delphine Seyrig often do not match the events that we see portrayed on screen. There is considerable doubt about whether many things did happen and what did happen is portrayed incredibly hazily. She has a memory of Giorgio Albertazzi being in her room – maybe Sacha Pitoeff shot her? or maybe Albertazzi attacked her? or else maybe they made love? At several points, Delphine Seyrig says she doesn’t want that part of a story to end a particular way – and not surprisingly it doesn’t.

The most striking symbol that Alain Resnais uses in the film is the statue in the garden – Giorgio Albertazzi sees that the man in the statue is guiding the woman, while Delphine Seyrig sees that the woman is holding the man back. Subtly, Resnais allows the camera to move up behind the figures in the statue and look out from adifferent point-of-view as each offers their interpretation. At the end of it, Resnais pulls back to a different point-of-view to say that either could be true just as equally as none of them could be, as they then debate over what the meaning of the dog on the statue is.

Last Year in Marienbad‘s vision of the past as a series of flitting ghost-like tableaux caught in time is both extraordinarily beautiful and hauntingly oppressive. The love that Giorgio Albertazzi begs Delphine Seyrig to give herself to is seen as alive and vital in contrast to the sterile beauty of the hotel. At one point, he wants to finish telling the story so that it can “become part of the past and frozen.” The ending is not that hopeful, rather more melancholic – the two lovers leave together but only to become figures lost in the endless garden of the grounds. It is as though Alain Resnais resignedly recognises that the vitality of the moment is something that is soon going to be occluded and swallowed up by the labyrinthine weight of the past. Profound matters indeed.

Trailer here