Crew

Director – Martyn Burke, Screenplay – Martyn Burke, Roy Moore & C.R. O’Christopher, Story – C.R. O’Christopher, Producers – Martyn Burke & Fran Rosati, Photography – Paul Van Der Linden, Aerial Photography – Clay Lacey, Music – Gil Melle, Special Photographic Effects – James Liles, Matte Paintings – Matthew Yuricich, Special Effects – Tom Fisher, Production Design – Roy Forge Smith. Production Company – Gene Slott Productions/The Canadian Film Development Corporation/Argosy Films.

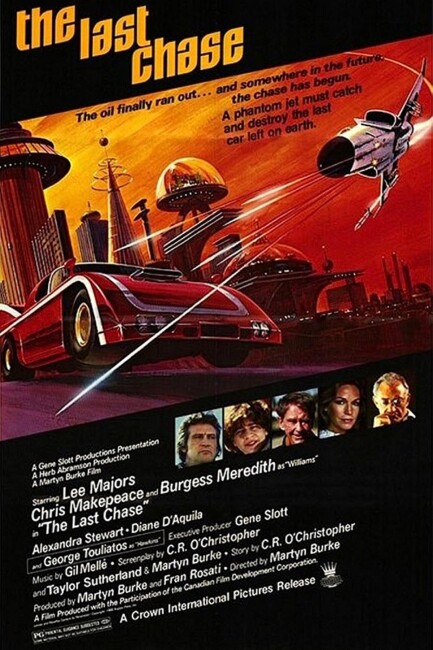

Cast

Lee Majors (Franklyn Hart), Burgess Meredith (Captain J.G. Williams), Chris Makepeace (Ring), George Touliatos (Hawkins), Alexandra Stewart (Eudora), Diane D’Aquila (Santana), Ben Gordon (Morely), Harvey Atkin (Jud)

Plot

It is twenty years after a plague has killed much of the world’s population. The government has banned all use of private cars following the end of the world’s oil supplies. Franklyn Hart is a former racing driver who has become a spokesman for the Mass Transit Authority. Rankling at the constant rules he is forced to obey, Franklyn finally stands up against the system in one of his public addresses. He is fired but is contacted by Ring, a runaway boarding school student who is also rebelling against the system. As police come to arrest him, Franklyn unveils the Porsche racing car he has kept hidden all these years. Joined by Ring, he takes off, heading across country to find the source of the Radio Free California pirate broadcasts. This is seen as an act of sedition by the authorities who make all effort to stop them. To do so, they bring in the aging former pilot Captain Williams and outfit him with an old fighter plane to hunt down and stop Franklyn.

The Last Chase was one of a mini spate of science-fiction films that came out around 1980. The most famous of these was Mad Max (1979), while also from Canada was Firebird 2150 A.D. (1980). Both of these sit in bridging period between the passing of the ideological dystopian film – Fahrenheit 451 (1966), THX 1138 (1971), Zardoz (1974) et al – and the coming of the futuristic action film set against a dark future – Crime Zone (1990), Demolition Man (1993), No Escape (1994). It is notable that Mad Max, Firebird 2150 A.D. and The Last Chase were made at the point when the OPEC-driven Oil Crisis of the 1970s was at its peak. The latter two works feature heroes behind the wheels of cars, something that is seen is a symbol of defiance against a system that seeks to prevent the use of private vehicle ownership.

In terms of its dystopian portrait, The Last Chase is a classic libertarian fantasy – car racing is equated with freedom and seen as a statement against a world that is governed by too many rules and by implication has become a nanny state that has taken away freedoms (such as private car ownership). The implication that never seems to occur to either The Last Chase or Firebird 2015 A.D. is that in a world where supplies are scarce to rebel by taking valuable supplies like gasoline simply so one can go joy-riding would be an act of supreme selfishness sort of in the same arena of reasoning that one’s desire to have a trophy trumps the right to kill an endangered animal.

The Last Chase never offers up a particularly practical scenario. The car’s tires are full of air and it is in perfect working order after being buried underground for twenty years. More to the point, the roads that Lee Majors drives across, even the dirt tracks, are perfectly usable and clean where in reality twenty years abandonment would have caused weeds to start growing through the paved surfaces and the unpaved ones to become completely overgrown. The surprise is also that the film does little to explore the world, which seems to vie between highly controlled civilised areas and wastelands that either resemble a standard post-holocaust scenario or are mostly barren.

There is the odd moment of wry humour – Chris Makepeace meets an old man in uniform and is told that he was a traffic warden: “He’s been waiting years to give a parking ticket,” to which Makepeace replies “I’ve been waiting years to get one.” In one of the more interesting touches, teenage nerd Chris Makepeace is seen as hacking into the government computer, which may well make The Last Chase the very first film about hacking, even though it is not called such and what would become the internet only exists as a very vague idea.

The film works passably but oddly the one place that it fails is largely the one area that it has been pitched – as an Action Film, at least by today’s standards. Most of the film just consists of Lee Majors driving the car down roads, the fighter plane flying through the air and nothing more than that. A modern sf/action film would have introduced Burgess Meredith’s nemesis far earlier in the game and had them meet up much sooner, or created far more in the way of episodic encounters along the route.

What is crucially lacking in much of this is drama. The car and plane finally meet up at the one-hour point and The Last Chase considerably picks up from there. There are a few sequences with the fighter plane doing strafing runs on the car, although not as many as one would think. Director Martyn Burke creates some fabulous shots, particularly of the plane coming down on the highway behind the car (even if that is disappointingly revealed to be a dream sequence) and a fine sequence with Lee Majors and Burgess Meredith engaged in a chicken race along a stretch of highway (even if it seems too small a stretch of road for either of them to get up to the 250 mph they do in a sequence that drags on for a minute).

The Last Chase was one of a handful of Canadian films made by Lee Majors just coming off the back of the huge success of tv’s The Six Million Dollar Man (1973-8). Majors is his usual stolid self, occasionally enlivened by a wry sense of humour. The best actor in the group is Burgess Meredith but for some reason he chooses to play the role of the pursuing nemesis with a silly crankiness, which considerably weakens the relationship that could have been built between he and Lee Majors and forms the backbone of the film. The one who emerges the best is George Touliatos who gets some fine dialogue and plays entertainingly to the gallery.