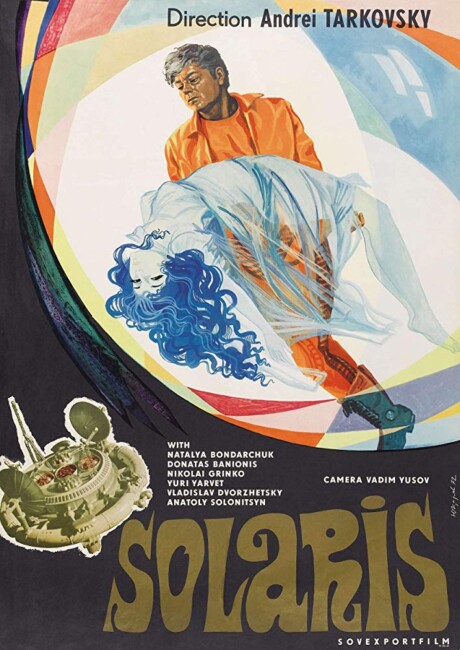

USSR. 1972.

Crew

Director – Andrei Tarkovsky, Screenplay – Andrei Tarkovsky & Friedrick Gorenstein, Based on the Novel by Stanislaw Lem, Photography – Vadim Youssov, Music – Eduard Artemiev, Art Direction – Mikhail Romadid. Production Company – Mosfilm.

Cast

Donatas Banionis (Chris Kelvin), Natalya Bondarchuk (Hari), Yuri Jarvet (Snouth), Anatoli Solinstin (Sartorius), Sos Sarkissian (Gibarian), Vadislav Dvorzhetski (Burton)

Plot

Psychologist Chris Kelvin is sent to investigate the mysterious happenings on a space station orbiting the water planet Solaris. There all but three of the personnel have either gone insane and killed themselves or each other. As Kelvin attempts to understand what has happened, his wife Hari appears to him – but she is dead, having committed suicide. Her mind is blank as to how she came to be there. Kelvin gradually realizes that it is not Hari but one of the manifestations drawn out of people’s memories that everybody on the station is haunted by. He attempts to get rid of Hari by putting her aboard a rocket but she returns. Even when she tries to kill herself, she keeps returning unhurt. Gradually, Kelvin comes to learn that she and the other apparitions are projections created by the planet below in an attempt to communicate with them.

The late Andrei Tarkovsky (1932-86) may well have been one of the world’s great directors. Almost every single one of Andrei Tarkovsky’s works receives rapturous reviews from people and have frequently been called some of the greatest films they have ever seen. The Russian-born Tarkovsky was slow to gain a reputation. It was not always easy to see his work, which, until Tarkovsky crossed over to the West in the early 1980s, was made in the Soviet Union. Tarkovsky was never particularly in favour with the Soviet authorities who felt his work – especially Andrei Rublyev (1969), which had fifteen minutes cut from it – was subversive and they would sometimes step in to ensure that his films did not receive widespread release. As Tarkovsky’s extraordinary body of work has become better circulated, what has been left behind is a series of films of mesmerizing power.

Andrei Tarkovsky was a filmmaker who made no concessions to Western-styled filmmaking. His films were long (none of them hail in at any less than 2½ hours – Solaris is one of his shorter at 165 minutes); his shots were slow and static – it was nothing for a Tarkovsky shot to go on for 2-3, sometimes ten minutes at a time; his messages were not directly spelt out but communicated by images and long, pregnant silences. Most of all, Tarkovsky’s work concerns a search for faith in the world. The extraordinary 3½ hour Andrei Rublyev is an historical epic concerning a 16th Century icon painter that portrays the almost piercing beauty that religion can represent in a world of overwhelming barbarism and brutality; Nostalgia (1983) concerns itself with a Russian man searching for spiritual meaning in modern Italy; and Stalker (1979) is similar to Andrei Rublyev in the theme of faith in invisible things amid an overwhelmingly desolate and dreary world. Tarkovsky’s major breakthrough in the West came with this complex, sometimes enigmatic science-fiction film, which won the Special Jury Prize at Cannes that year.

Solaris could almost be called a ghost story – one that is set in a space station in lieu of a haunted house and where the apparitions are psychological ghosts made manifest. Certainly, Tarkovsky’s approach (at least initially) is akin to a haunted house film – figures momentarily seen flitting between the debris-strewn corridors, people hiding never-seen others in their rooms and the enigmatic appearance of the dead wife Natalya Bondarchuk in Donatas Banionis’s locked room. Where another film might be happy with merely playing pop-up scares on an audience – a comparable example might be the silly Event Horizon (1997), which merely locates a standard possession/gateway to Hell story aboard a spaceship – Tarkovsky heads deeper. To maintain the science-fiction ghost story analogy, Tarkovsky recognizes the place where all effective ghost stories lie – in a psychological relationship between the haunted mortal and the apparition.

One element of Andrei Tarkovsky’s films is the weight that the past holds over the individual. [Tarkovsky’s next film, the autobiographical The Mirror (1976), is a series of images as a dying man dreams of his own past]. All of Tarkovsky’s science-fiction films have an element of wish fulfillment fantasy to them – of the travellers heading towards a mysterious place that is supposed to grant one’s heart’s desire in Stalker, of the hero in The Sacrifice (1986) offering to sacrifice everything he has if nuclear war can be turned back – only for the protagonists to realise that their wish made manifest is not everything they imagined it might be.

In Solaris, the hero is reconciled with his late wife only to find that the simulation he is confronted with is something alien to him. Solaris is at its most haunting during these images of Donatas Banionis confronting his incarnated wife’s utter alienness – her tearing her way through steel bulkheads because she does not understand the concept of opening a door, returning after Banionis fires her off in a rocket – that gradually merge into a sense of nightmarishness as she begins to understand the suffering she is causing and tries to spare him by drinking a lethal dose of liquid oxygen, only to still get up unaffected.

Solaris is a film suffused with haunting and beautiful images – as any Andrei Tarkovsky film always was. There is one extraordinarily lovely image as the station momentarily enters a zero gravity zone where candles, books and the two lovers gently take off and float in mid-air. Although the one image that everybody remembers about Solaris is the enigmatic final shot that starts in Kelvin’s father’s house (where the film began) and then pulls back up overhead and keeps on going beyond the property to show that the road beyond runs straight into the sea and the house is on an island sitting in the middle of the ocean.

When released in the West, Solaris was billed as “the Russian 2001“, which it certainly bears much in common with it – although there is no evidence that Andrei Tarkovsky had seen 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) at the time he made Solaris in the Soviet Union where Western films were almost exclusively banned. (Although in his memoir Sculpting in Time (1986), Tarkovsky is scatching of the soullessness of 2001). Instead, what Tarkovsky drew from was a 1961 novel by Polish author Stanislaw Lem, one of the most celebrated science-fiction writers in the Communist Bloc. [Solaris underwent an earlier 2½ hour two-part adaptation for Russian television in 1968].

Certainly, Solaris and 2001 often have a great deal in common – both are set on a space station; both stations have a technological look that is dominated by blank, antisceptic white corridors; and in both the thrust of the film is towards understanding the nature of something alien and incomprehensible. At the same time, Solaris is also a very different film to 2001. Where Stanley Kubrick had a fascination with the nuts and bolts of science-fiction hardware and the poetry of spaceflight, Andrei Tarkovsky eschews almost any externals – there is only a single exterior model shot of the space station shown throughout and the initial journey to the space station is not depicted at all. The space station sets are excellent, but where 2001 showed technology overshadowing humans, Solaris is almost akin to Dark Star (1974) in its depiction of this triumphant marvel of technology lying in messy disordered chaos.

Most of all is the difference in the nature of the transcendental breakthrough that the two films build towards. In both films, the breakthrough that the protagonist at the centre of the story makes is one whose nature is left beyond the audience. 2001 trades in light shows and surreal visions of hotel rooms, while Solaris has hero Donatas Banionis having reached his conceptual breakthrough and standing on the recreated house on the planet – although quite what that means in terms of his relationship to and understanding of the planet is unclear to us.

Where 2001‘s journey into transcendental space ended with Keir Dullea’s astronaut having to leave human form behind and evolve into a child of the stars, Solaris‘s travels in almost entirely the opposite direction. Whereas 2001 ventured outward and away from humanity, Solaris sentimentally returns to lost memories of its hero’s childhood. In this regard, Solaris is not unakin, albeit more benignly so, to other science-fiction films such as Forbidden Planet (1956) and Sphere (1998) that see contact with a transcendental force as not being a transformational experience, as 2001 does, but rather one that would only magnify what is inside the human heart.

Andrei Tarkovsky’s two other ventures into genre cinema were the masterful Stalker (1979) about a group of people on an expedition into an enigmatic alien zone that contains a room that is supposed to make one’s greatest desire come true; and The Sacrifice (1986) set on the fall of the nuclear holocaust about a man who prays that things will be turned back. Andrey Tarkovsky. A Cinema Prayer (2019) is a documentary about Tarkovsky’s life and career.

Other science-fiction films adapted from Stanislaw Lem’s books are First Spaceship on Venus (1959), Ikarie XB-1/Voyage to the End of the Universe (1963), Test Pilot Pirx (1979), 1 (2009), the part-animated The Congress (2013) and His Master’s Voice (2018).

The Stanislaw Lem novel had earlier been adapted as a 2½ hour movie for Russian television with Solaris (1968). Solaris (2002) was an occasionally interesting but generally unsatisfying English-language remake from Steven Soderbergh starring George Clooney as Kelvin. The story of wife tearing through the door was also recounted and turned into a peculiarly haunting metaphor for relationships in the brilliant Australian black comedy He Died with a Felafel in His Hand (2000).

Trailer here