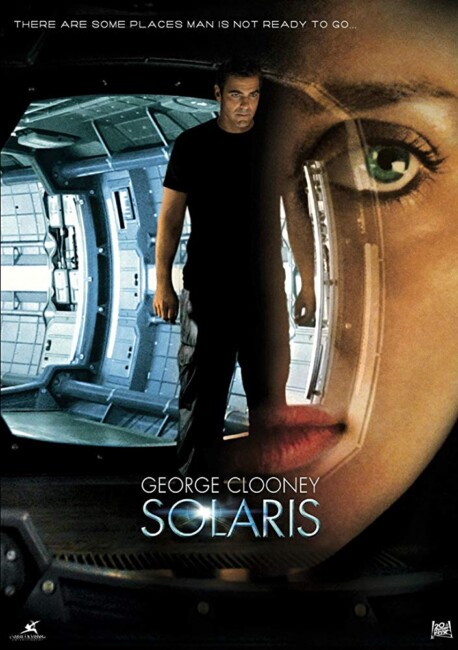

USA. 2002.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Steven Soderbergh, Based on the Novel by Stanislaw Lem, Producers – James Cameron, Jon Landau & Rae Sanchini, Photography – Peter Andrews [Steven Soderbergh], Music – Cliff Martinez, Visual Effects – Cinesite (Supervisor – Thomas J. Smith), Planet Effects – Rhythm and Hues (Supervisor – Richard Hollander), Special Effects Supervisor – Kevin Hannigan, Production Design – Philip Messina. Production Company – Lightstorm Entertainment.

Cast

George Clooney (Dr Chris Kelvin), Natascha McElhone (Rheya Kelvin), Jeremy Davies (Snow), Viola Davis (Dr Gordon), Ulrich Tukur (Dr Gibarian), Shane Skelton (Michael Gibarian)

Plot

Psychologist Chris Kelvin is asked to go on a mission to investigate what has happened on the space station orbiting the planet Solaris. Kelvin’s old friend Gibarian has sent a message, begging Kelvin to come and help them. Arriving on the space station, Kelvin finds that only two of the personnel are still alive, both half-insane and huddled in fear. When he wakes up after the first night, Kelvin is startled to find his wife Rheya, who committed suicide, there beside him. She has no idea how she came to be there and he gradually realizes that she is only imbued with the memories that he has of her. Even when he ejects her in an escape shuttle, she returns unaffected. He slowly comes under her influence and begins to fall in love with her, even though the others warn him that she is a simulation created by the planet below.

Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky was one of the greatest of all 20th Century directors and his Solaris (1972) is a genuine science-fiction masterpiece. Solaris was made in the early 1970s in the shadow of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – it was even nicknamed “the Russian 2001.” Both 2001 and Solaris are films that reach toward the vast and transcendental. Yet, where 2001 has human form evolving beyond a cold technological future to become an enigmatic creature of the stars, Solaris travels in opposite directions as the transcendental envelops its hero in sentimental images of his past. With its beautiful images of humanity confronting the inexplicably alien and the incredibly haunting, enigmatic final image, Solaris is a modern science-fiction classic.

This is the Hollywood remake. While most Hollywood remakes of foreign-language films end up being crass, there was some hope in that the Solaris remake was handled by no less than Steven Soderbergh. Steven Soderbergh is current intellectual flavour of the Hollywood mainstream. Soderbergh first emerged with the festival hit Sex, Lies and Videotape (1989). For a time after that, Soderbergh seemed like being a one-hit wonder. His subsequent films – Kafka (1991), which tried to tell a fictionalised biography of Franz Kafka as a mad scientist tale, The Underneath (1995), Gray’s Anatomy (1996) and Schizopolis (1996) – were flops. However, Soderbergh gained his second wind with the breathtakingly cool crime thriller Out of Sight (1998), which still remains his (and George Clooney’s) best film. Soderbergh went onto make The Limey (1999), and the twin breakthrough successes of Erin Brockovich (2000) and Traffic (2000), which had him uniquely nominated for the Best Director Oscar twice in the same year, and the remake of Ocean’s 11 (2001) and sequels, and subsequently The Good German (2006), the Che films, The Informant (2009), a further science-fiction film Contagion (2011), Haywire (2012), Magic Mike (2012), the asylum horror film Unsane (2018) and the ghost story Presence (2024). Solaris is no less than the fifth remake that Soderbergh has overseen – from directing Traffic (which was based on a British mini-series) and Ocean’s 11, to acting as producer on the American remakes of Nightwatch (1998) and Insomnia (2002). [To doubly ensure that the remake is in good hands, Solaris 2002 is produced by James Cameron, the director of films like The Terminator (1984), Aliens (1986), The Abyss (1989), Titanic (1997) and Avatar (2009), and his Lightstorm Entertainment production company].

Solaris 2002 emerged to a mixed response. There was a deeply uncertain promotional campaign from 20th Century Fox, which downplayed the science-fiction content and seemed to be trying to sell the film as a romance. There seemed to be some behind-the-scenes friction with George Clooney appearing taciturn in interviews and reluctant to promote the film. Both critical and audience response was deeply divided, with most average cinemagoers coming out grumbling about Solaris being slow, boring and difficult to understand. In fact, more public attention seemed to focus on George Clooney’s naked butt than any of the film’s deeper philosophical issues or comparisons with the original film.

Solaris 2002 runs at 99 minutes, which is more than an entire hour shorter than the original. Steven Soderbergh covers all the basics during that time. Largely, he trims Andrei Tarkovsky’s proclivity for long ponderous shots – it was nothing for shots in a Tarkovsky film to go on for 2-3, sometimes 10, minutes at a time. Occasionally this Solaris seems a little hurried in development – one minute George Clooney is confronting Natascha McElhone’s doppelganger in his room, the next he is dumping her into space in the escape pod without any understanding of why being given to us. Nevertheless, Steven Soderbergh follows the original closely for the better part of the running time. Although oddly, no credit whatsoever is given to Andrei Tarkovsky (and his co-writer Friedrick Gorenstein). There is credit given to Stanislaw Lem’s original 1961 novel and thanks at the very end to Mosfilm, the Soviet production company, but none to Andrei Tarkovsky, even though Solaris 2002 is based much more on the 1972 film than it ever was Stanislaw Lem’s novel. Forgotten in all of this seems to be the original film version of the book, which had earlier been adapted as a 2½ hour movie for Russian television with Solaris (1968).

Solaris 2002 is also much more of a science-fiction film than Solaris 1972 was. Andrei Tarkovsky’s vision of the future extended little beyond the space station – the futuristic scenes simply consisted of a car driving through the Moscow streets. Steven Soderbergh concerns himself with the details of the future far more than Andrei Tarkovsky did, adding small touches of advanced technology and clothing styles. The characters here are constantly analysing Solaris and the phenomenon in terms of physics and science, and there is much more in the way of the traditional trappings of science-fiction hardware. (Possibly this is the influence of James Cameron, who is perhaps the foremost director of hardware and technology driven science-fiction at the moment).

Even more so, Soderbergh strengthens Solaris as a story. He gives the set-up more coherence and depth and ties it together neatly – adding, for instance, Gibarian as a colleague of Kelvin’s, which gives much more personal reason for Kelvin to travel to the station – while posing some intriguing questions about the nature of the phenomenon. Soderbergh does create some entirely original scenes towards the end – introducing a Jeremy Davies simulacrum and a confusing scene where Gibarian’s ghost returns, a subplot about eliminating the simulacra with Hicks radiation and the climactic scenes with the station’s crash into the atmosphere and the escape plan – although these do not add much.

Most of all, Soderbergh strengthens the relationship between Kelvin and his wife. Steven Soderbergh’s films come with a cool meditative intelligence to them. The best parts of Solaris 2002 are those subtly delineating the relationship between George Clooney and Natascha McElhone’s doppelganger. Andrei Tarkovsky never dwelt on the details of their relationship and her death at all, whereas Steven Soderbergh gives us detailed flashbacks that take us from the beginning of their relationship through to her eventual suicide. Natascha McElhone gives a blankly haunted performance and Steven Soderbergh does a fine job of portraying George Clooney’s fear, love, hope and protection of her. Soderbergh writes some particularly good scenes here, especially good being the second Natascha McElhone’s shock at learning that George Clooney dumped the first simulacrum into space. Although, perhaps Soderbergh’s intention to focus on the relationship ultimately overbalances the story. He does so so much that Solaris seems almost irrelevant to the film. There is no sense that the planet is a living entity trying to communicate with the astronauts, indeed Soderbergh leaves the agency behind things such an existential blank that it could be possible to remove Solaris from the story altogether.

The most frustrating part of the remake is the new ending. Andrei Tarkovsky ended Solaris 1972 with an unforgettable and haunting image – that of Kelvin standing in his home and the camera’s gradual pullback to show that this is a simulation that exists on a small island in the middle of the ocean. Steven Soderbergh throws this out and instead inserts a puzzling ending where George Clooney stands at the airlock uncertain about joining Viola Davis as she goes to return to Earth in the escape pod. We then see him in his apartment back on Earth, just as we did in the beginning, dicing vegetables and then cutting his finger all over again but with things subtly changed this time. Soderbergh then cuts back to the station as it goes down into the atmosphere where Clooney is rejoined by Natascha McElhone who tells him that they are now in a place “where all is forgiven.” Quite what is going on in these scenes is unclear. The scenes back in the apartment are not unlike the unicorn dream and ending of Blade Runner (1982), which left one with the impression that Harrison Ford might also be a replicant, with Soderbergh here leaving you unsure if maybe George Clooney is not a dreamed figure himself. The ending with George Clooney and Natascha McElhone meeting in the afterlife has a corny sentimentality to it – it seems like little more than a version of Star Trek: Generations (1994) wherein Captain Kirk ended up in an idealized dream world of his greatest desire made manifest. It is a critical miscuing of the film, ending on a puzzling medley of scenes that leaves the audience in a state of confusion. Andrei Tarkovsky ended with a stark image of man up against the bafflingly inexplicable; by contrast, Steven Soderbergh arrives at a series of dog ends of ideas and resolves nothing.

Of the two films, Solaris 2002 is a more intimate film but Steven Soderbergh, though he asks some intriguing questions, fumbles the story when it comes to the larger canvas; on the other hand, Solaris 1972 still remains the starker, more powerful film – its massive canvas of memory and the vastly inexplicable with humanity bared between the two still remains an indelibly stark vision despite the curtain of subtitles. The problem that Solaris 2002 faced is that it is not an easy multiplex film, it is an arthouse film. It was made in a time when meditative, existential science-fiction had become a thing of the past, where science-fiction had almost entirely been taken over by routine CGI amazement and light popcorn adventure. Not that a return to intellectual, character-driven science-fiction is an unwelcome thing. Solaris is also a film that comes with no easy solutions and where much of what happens, especially at the end, is left bafflingly ambiguous and unclear. While Solaris 1972 took us to the breathtakingly enigmatic, Solaris 2002 merely grinds to a halt in uncertain confusion. You cannot decry Steven Soderbergh for aiming at places well beyond the reach of the average popcorn film, but Solaris‘s failure is one that he must also share in that he fails to lead to a satisfying resolution.

Steven Soderbergh’s other films of genre interest are the fictionalised biopic Kafka (1991), the surreal Schizopolis (1996), the plague outbreak drama Contagion (2011), the asylum horror film Unsane (2018) and the ghost story Presence (2024). Soderbergh has also produced a number of films, including the genre likes of the English language remake of Nightwatch (1998), Pleasantville (1998), Christopher Nolan’s remake of Insomnia (2002), the time travel film The Jacket (2005), Richard Linklater’s Philip K. Dick adaptation A Scanner Darkly (2006), the ghost story Wind Chill (2007), the evil child film We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011) and Bill & Ted Face the Music (2020).

(Nominee for Best Actress (Natascha McElhone) at this site’s Best of 2002 Awards).

Trailer here