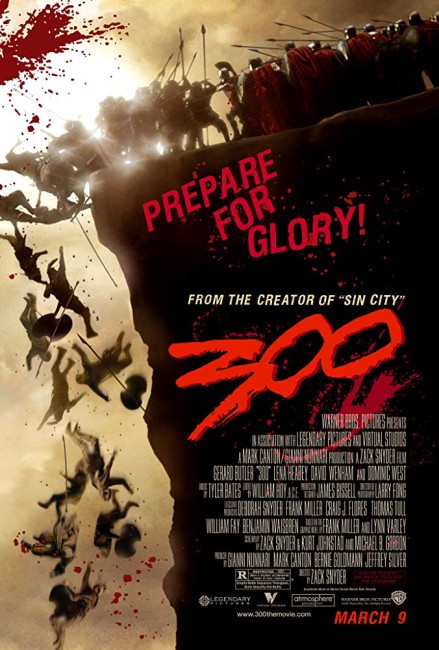

USA. 2007.

Crew

Director – Zack Snyder, Screenplay – Michael B. Gordon, Kurt Johnstad & Zack Snyder, Based on the Graphic Novel by Frank Miller & Lynn Varley, Producers – Mark Canton, Bernie Goldmann, Gianni Nunnari & Jeffrey Silver, Photography – Larry Fong, Music – Tyler Bates, Visual Effects Supervisor – Chris Watts, Visual Effects – Animal Logic (Supervisor – Kirsty Millar), Buzz Image Group, Hybride, Hydraulx, Lola VFX, Pixel Magic, Scarline & Screaming Dead Monkey/At the Post, Special Effects Supervisor – Louis Craig, Creature/Makeup Effects – Mark Rappaport & Shaun Smith, Production Design – James D. Bissell. Production Company – Legendary Pictures/Virtual Studios/Hollywood Gang/Atmosphere Pictures MM.

Cast

Gerard Butler (King Leonidas), Lena Headey (Queen Gorgo), Dominic West (Theron), David Wenham (Dilios), Rodrigo Santoro (King Xerxes), Vincent Regan (Captain Artemis), Andrew Tiernan (Ephialtes), Andrew Pleavin (Daxos), Michael Fassbender (Stelios), Tom Wisdom (Astinos), Peter Mensah (Persian Messenger), Tyrone Benskin (Persian Emissary), Tyler Neitzel (Young Leonidas), Kelly Craig (Oracle Girl)

Plot

480 B.C. The kingdom of Sparta, which prides itself on its fierce and uncompromising warrior spirit, receives a request to submit and pay obeisance to Xerxes, the godking of Persia. The Spartan king Leonidas refuses and instead has the Persian messenger killed. This earns the wrath of Xerxes who heads towards Sparta with an army of a million soldiers. Leonidas seeks the oracular advice of the diseased Ephors who say that he must not raise the Spartan army against Xerxes because it will tarnish the coming Carneian festival. And so, rather than raise the city’s army, Leonidas forms a unit of 300 of his best men and sets out to a narrow pass known as The Hot Gates. There Leonidas and the 300 Spartans hold off against the overwhelming numbers of the Persian army, fiercely slaughtering everything that Xerxes brings against them, even when they know that this will mean their own deaths.

The name of Frank Miller is a legendary one in the annals of comic-books/graphic novels. As both artist and writer, Frank Miller began with DC and Marvel, working on series such as The Amazing Spiderman, The Incredible Hulk, Fantastic Four and John Carter of Mars, as well as creating DC’s Ronin series. Miller started to come to attention during the early 1980s with his redefinition of Marvel’s Daredevil. The work that made Frank Miller into a name that everybody paid attention to was The Dark Knight Returns (1986), which created the modern dark, grim and brooding Batman. Into the 1990s, Miller began to work as an independent with series such as Give Me Liberty (1990), Hard Boiled (1990-3), Big Guy and Rusty the Robot (1996) and most famously Sin City (1991-2000). Miller’s stylised artwork and incisive writing served to make these into greatly sought collectors’ classics.

In recent years, Frank Miller has drawn increasing attention from filmmakers. He worked as screenwriter on RoboCop 2 (1990) and RoboCop 3 (1993), although was vocally dissatisfied with the results. During the recent spate of Marvel Comics film adaptations, both the screen versions of Daredevil (1993) and Elektra (2005) drew heavily on Frank Miller’s interpretations – in fact, the super-assassin Elektra was originally a Miller creation – although he was not involved in either film. However, what caught everyone’s attention was Robert Rodriguez’s stunning adaptation of Sin City (2005), where Rodriguez went as far as to create the film as a literalization of Miller’s stylized comic-book panels. Rodriguez was so enamoured of Miller’s inspiration that he brought him on board to consult and quit the Director’s Guild when they refused to allow Miller to be credited as co-director. Due to the success of Sin City and 300, Miller was subsequently given the directorial chair of the comic-book adaptation The Spirit (2008) and later reteamed with Rodriguez for Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (2014). He subsequently also saw animated adaptations of his classic graphic novels with Batman: Year One (2011), which had been much discussed as a film project, and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns Part I (2012), Batman: The Dark Knight Returns Part II (2013) and the tv series Cursed (2020), as well as the sequel 300: Rise of an Empire (2014).

Frank Miller’s 300 (1998), a five issue graphic novel co-written with his then wife Lynn Varley and published by Dark Horse, is based on the historical Battle of Thermopylae in 480 B.C. In particular, Miller took 300 from the accounts given by the Greek historian Herodotus in his The Histories (c440 B.C.). At this period in history, King Xerxes I of Persia was in the process of subjugating Egypt, Babylon and the Greek mainland. Several of the Greek city states formed an alliance to stand up against Xerxes. The most famous of these battles was fought at Thermopylae (which translates as ‘The Hot Gates’), a narrow pass in central Greece, by a small force of 300 men led by the Spartan king Leonidas who stood against a Persian force that historians generally agree upon as consisting of around 200,000 men. (The number of 300 on the Spartan side is somewhat misleading as there were actually around 5000 troops sent by various other Greek states, something that is only partly touched upon by the film – although, in fairness, most of these were dismissed by the time of the last stand). Though the Spartan siege was unsuccessful and the Persian army advanced to conquer Athens, the Persians were driven back by the Greeks at the Battle of Salamis in 480 B.C. and the Spartan-led Battle of Plataea in 479 B.C. However, the Battle of Thermopylae has gained fame for its extraordinary heroism in terms of people prepared to fight to what they know as being their own deaths for the sake of honour and in the ability of a few to exert massive losses against overwhelmingly larger numbers. The events of the Battle of Thermopylae had previously been placed on film in The 300 Spartans (1962), which is what inspired Frank Miller’s interest in the story.

This film adaptation of Frank Miller’s 300 comes from director Zack Snyder. Zack Snyder made his screen debut with the remake of Dawn of the Dead (2004). Though the remake was popular, I was not a particular fan – Snyder needlessly reconceptualized the original, eliminating the social subtext and failed to replicate the gore scenes that had made the original Dawn of the Dead (1978) a classic. Snyder does seem to be a genre fan though. 300 received a rapturous response, both at the box-office and especially from comic-book fans. He next signed on to bring another classic graphic novel series to the screen with Alan Moore’s Watchmen (2009). He subsequently made the animated Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga’Hoole (2010), the fantasy action film Sucker Punch (2011), Man of Steel (2013), Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016) and Justice League (2017), plus his extended cut of the latter with Zack Snyder’s Justice League (2021), the zombie film Army of the Dead (2021) and the space opera Rebel Moon – A Child of Fire: Part One (2023) and Rebel Moon – Part Two: The Scargiver (2024). He also wrote/produced 300: Rise of an Empire (2014) and produced Suicide Squad (2016), Wonder Woman (2017), Aquaman (2018), Wonder Woman 1984/WW84 (2020), Army of Thieves (2021) and The Suicide Squad (2021).

Nominally, 300 falls into the fad for historical films that we have had in recent years following the success of Gladiator (2000), which has included the likes of Alexander (2004), King Arthur (2004), Troy (2004), Kingdom of Heaven (2005) and Tristan + Isolde (2006). Zack Snyder’s stated intention was to make an adaptation of Frank Miller’s graphic novel more so than any historically accurate account of the Battle of Thermopylae. Rather than an historical film, 300 should be considered more like a fantasy film that happens to use real events as its basis. The nearest cinematic point of comparison might be Fellini’s Casanova (1976), which tells a biography of the famous lover set in 18th Century Italy where Fellini abandoned any interest in historical realism and offered up a gorgeously decadent array of costumes, surreal sets and extravagantly stylised dramatics.

Like Robert Rodriguez before him in Sin City, Zack Snyder statedly set out to directorially replicate the individual frames of Frank Miller’s graphic novel. This results in a visually extraordinary look, quite unlike any film you have seen before. From the colour toning to the buffed and hyper-eroticised bodies, the slow-motion action poses to the scenery that surrounds the characters, sometimes even the colour of the characters’ eyes, all has been stylised to the point that they look like the live-action replication of drawn images. There are stunningly fantasticized visions – the sky literally becoming darkened with a rain of Persian arrows; the sequence where the Spartan phalanx drives the Persians back over the edge of the cliff in slow-motion; and especially the vision that the Spartans are greeted with upon arriving at the pass of the Persian ships being wrecked and sunken in a storm. The entire film was shot inside a Montreal studio using the digital backlot technique (wherein the various sets and surroundings were inserted via CGI and the actors performed in front of blue and green screens) – something that was also used with striking results in the previous Frank Miller adaptation Sin City.

Zack Snyder frequently ventures forth into outright fantasy elements. Indeed, were one to know nothing about the film’s origin or the Battle of Thermopylae, you would be tempted to throw 300 in with the new bunch of fantasy films viz The Lord of the Rings more than you would with historical films like Gladiator et al. The traitor Ephialtes (an historical figure whose name became so despised that it now means ‘traitor’ in Greek) has been transformed into a hunchback so deformed he could be a brother to The Elephant Man (1980). King Xerxes, who was to all historical accounts a physically average person, has become a giant who towers at least ten feet tall and comes bedecked in gold jewellery and with piercings all over his body. The Persian army contains an even taller range of giants who look more like Balrogs than anything human; even a giant torturer who has crab pincers in lieu of hands, which are used to guillotine soldiers that fail. The Persian army also contains battle rhinoceroses that are about the size of elephants and elephants that are about the size of six-story buildings. Earlier in the piece, King Leonidas goes to consult the Ephors, who historically are no more than an elite group of Spartan political counsellors, but here are portrayed as disease-ridden and morally degenerate old men that are no longer fully human and take the most beautiful virgins – Kelly Craig in a vividly erotic dance – and transform them into oracular voices. Directorially, 300 is an extraordinary film and one gives Zack Snyder top marks in terms of what he creates on screen.

At the same time as you admire Zack Snyder’s visuals, on another level 300 sits atop an uneasy body of subtexts. In various promotional interviews for the film, Zack Snyder assiduously denied that there was any political reading to 300. Not that a creator denying there are any other levels to a film than what they intended necessarily means that there are not – Leni Riefenstahl assiduously denied there were any political meaning to films like The Triumph of the Will (1934) and Olympia (1938) but almost all today read her works as creating propagandist images of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. A creator is a product of various social and psychological forces around them and, in that much of creative output comes from a place in the subconscious, it is not difficult to see that works of art sometimes convey far more than what the creator says or is aware that they do. I hugely enjoyed 300 but it is a film where you almost have to tune out any kind of awareness of contemporary world politics in order to do so.

In pre-release, everyone at the studio seemed deadly afraid that the film would be seen in terms of current US-Middle Eastern political tension. Despite what the studio wants audiences to think, this is exactly what 300 comes out doing. It is perhaps too much to talk about historical accuracy in a film that delights in turning itself into something entirely fantastical. However, one aspect of the film is troubling – and that is that the film deliberately distorts the nature of Spartan and Persian societies of the era. The Spartan military code does at least seem to be reasonably accurately portrayed. However, what is not is the fact that in the film The Spartans are seen as white Caucasian men rather than Greeks. Moreover, they are off to fight for a democratic ideal of freedom, when in fact Sparta was a monarchist city state. By contrast, the Persians are seen as being of non-Caucasian ethnicity (and considering the giants among their numbers, possibly not even human at all), as a degenerate and corrupt society, and in the service of a vain king who maintains an autocratic slave-holding regime. The irony that comes here is that Persian society of the era would probably be closer to what we regard as a democracy today than the Spartan society was, while the Spartans held a substantially higher number of slaves per head of population than the Persians ever did.

There are other uneasy associations made – the Spartans are portrayed as buffed and physically virile heroes who all enjoy heterosexual relationships (only those who have sons are chosen to go into battle), while the man-boy love of other Greek states is deplored in a speech by Gerard Butler at the very start; whereas the Persians are portrayed as overly ornamented and gilded as well as bodily pierced (which is invoked to suggest a cultural decadence), while Xerxes has a decided sexual androgyny and keeps a harem of what we learn on the end credits are transsexuals.

300 seems to work on an comically exaggerated level that suggests it is a film about white, freedom-loving, heterosexual men standing up against degenerate, democracy-hating peoples of multi-ethnic and alternate sexual preferences (with the crippled and deformed also thrown in there for good measure). You keep suspecting that half the reason that Zack Snyder made 300 into so much of a fantasy film is that he would have been lynched by various minority groups if any of this had been played as a serious historical film. Understandably, the modern-day Persians (Iran) became upset at their portrayal in the film with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (who seems to be doing his own thing these days in standing up against vastly larger political forces with small numbers) even going so far as to publicly denounce the film as American propaganda.

Oddly, you do suspect that Ahmadinejad, lunatic and all that he is, does have a point. It is not hard to read 300 in terms of contemporary politics. Indeed, you could compare 300 back to 2001 when Columbia released Black Hawk Down (2001). There are similarities between the two films – both are about small military forces in a standoff against overwhelming odds where the side that we might regard as the heroes in any other war film ends up being defeated. Black Hawk Down had been intended for release several months later but after 9/11 the studio hurriedly pushed its schedule up to take advantage of the upsurge in patriotism. Black Hawk Down is a cry of outrage about how American forces (the fact that it was an international UN body that was attacked in Mogadishu was handily omitted) were humiliated by ragtag foreign forces. It was a rallying cry to war.

300 embodies the same message. It is a film about not so much a monarchist Greek city-state going to war as it is a film about freedom-loving Caucasian soldiers going off to war against a cruel and evil democracy-spurning Middle Eastern empire. It is really, really, really hard despite what the studio publicity department and Zack Snyder might wish to not read 300 in terms of being a rallying cry towards self-sacrificing heroism in the name of nationalistic honour. Had 300 come out at any other time than now it would have been a different film. If you apply it to a battle zone such as modern-day Iraq where the US seems to be badly losing at the time the film came out, 300 starts to feel like all but a military recruitment video for death by glory in some kind of insanely machismo notion of nationalistic loyalty.

Zack Synder announced interest in a sequel Xerxes. This eventually emerged under a different director as 300: Rise of an Empire (2014) with Snyder directing and producing, which is less a prequel than a parellel story that features return performances from many of the actors here. 300 was spoofed in Meet the Spartans (2008).

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 2007 list. Winner for Best Director (Zack Snyder) and Best Cinematography, Nominee for Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actor (Gerard Butler), Best Makeup Effects and Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 2007 Awards).

Trailer here