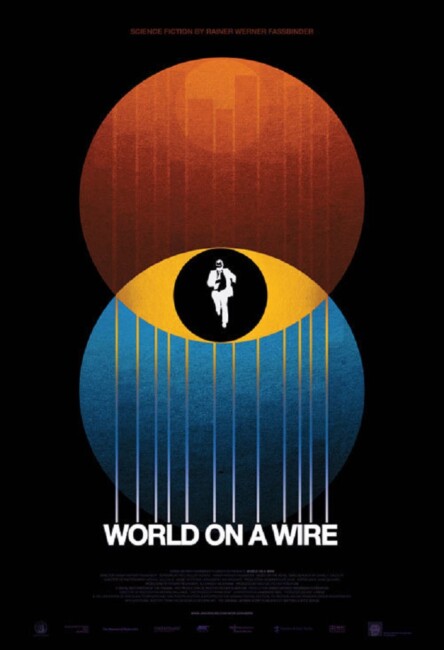

(Welt Am Draht)

Crew

Director – Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Screenplay – Rainer Werner Fassbinder & Fritz Muller-Schurtz, Based on the Novel Simulacron 3 (1964) by Daniel F. Galouye, Producers – Peter Marthesheimer & Alexander Wesemann, Photography – Michael Ballhaus & Ulrich Prinz, Music – Gottfried Hungsberg, Production Design – Horst Giese, Walter Koch & Kurt Raab. Production Company – Westdeutscher Rundfunk.

Cast

Klaus Löwitsch (Fred Stiller), Barbara Valentin (Gloria Fromm), Mascha Rabben (Eva Vollmer), Wolfgang Schenck (Franz Hahn), Karl-Heinz Vosgereau (Herbert Siskins), Ulli Lommel (Rupp), Kurt Raab (Mark Holm), Gunther Lamprecht (Fritz Walfang), Joachim Hansen (Hans Edelkern), Ivan Desny (Gunther Lause), Adrian Hooven [Hoven] (Professor Henri Vollmer), Margit Carstensen (Maya Schmidt-Gentner), Reiner Hauer (Inspector Lehner), Heinz Meier (Secretary of State Von Weinlaub), Gottfried John (Einstein)

Plot

At the IKZ Institute, Professor Henri Vollmer panics at something he has discovered and is then found dead inside the computer room. Fred Stiller is appointed Vollmer’s successor as the institute’s head of technology. He is placed in charge of Simulacron, a vast project to create a simulated world inside the computer environment inhabited by artificial people unaware of their true nature. At a party, Stiller is contacted by the security head Gunther Lause who tries to tell him what Vollmer knew but he disappears when Stiller momentarily turns away. Afterwards, Stiller is baffled as there is no record and nobody has any memory of Lause, while somebody else claims to have always been the security head. Stiller begins to investigate the increasingly mysterious circumstances of Vollmer’s death, while at the same time efforts are made to silence him. Gradually, Stiller comes to the realisation that he and the entire world he is in might be yet another level of simulation inside the computer program. Because he has uncovered this knowledge, this now marks him for deletion by the mysterious controllers.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1945-82) was one of the key directors of the New German Cinema movement in the 1970s, a period that also saw the emergence of people like Werner Herzog and Wim Wenders. Between 1966 and his death in 1982 from a fatal mix of cocaine and sleeping pills, Fassbinder had a breakneck regimen in which he made fourteen tv movies, two tv mini-series and 24 theatrically released films. Fassbinder’s international acclaim grew with works such as The Marriage of Maria Braun (1978), Lili Marleen (1981), Lola (1981), Querelle (1982) and Veronika Voss (1982), as well as the tv mini-series Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980). An openly gay man, Fassbinder wilfully courted controversy on both sides of the fence. This is reflected in his work, which frequently deals with social outsiders and iconoclasts, and often highlighted gay themes before such gained a widespread acceptability.

World on a Wire was Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s sole venture into science-fiction, although he did make an acting appearance as the detective hero in the futuristic action thriller Kamikaze 1989 (1982). The only other venture he made into genre material was as producer and an actor in Ulli Lommel’s directing debut The Tenderness of the Wolves (1973) based on the life of German serial killer Fritz Haarmann.

World on a Wire is adapted from the novel Simulacron 3 (1964) by American author Daniel F. Galouye. The same book was later remade as The Thirteenth Floor (1999), an English-language film that was also produced in Germany by Roland Emmerich. World on a Wire was made by Fassbinder for television, originally airing in two two-hour parts. It was out of circulation and only existed by reputation for many years until it was given a restoration that premiered at the 60th Berlin International Film Festival in 2010.

I had always assumed that the very first film about Virtual Reality was Welcome to Blood City (1977), which came out before anybody had ever coined the term, while on television some of the Doctor Who episode The Deadly Assassin (1976) took place inside a virtual computer environment. However, World on a Wire predates these and reveals that it in fact was the first film to use Virtual Reality themes.

The great surprise is how almost every trope of the Virtual Reality film has its beginnings here. Films such as Total Recall (1990), Open Your Eyes (1997), eXistenZ (1999), Avalon (2001), Paprika (2006) – all of their basic ideas are laid down here. In particular, works such as Dark City (1998) with its revelation of an artificial simulation where people’s memories are constantly being re-edited and The Matrix (1999) with the idea that we are all living in a simulated world, even Inception (2010) with its vision of multiple nested levels of reality that may well also include this one, all draw from what was first conducted here. (World on a Wire was not seen widely outside of West Germany so it is unlikely that any of these draw direct influence from the film).

Much of World on a Wire is as relevant today as when it was made. The film manages to predate the idea of Virtual Reality helmets with users entering the simulation while lying on couches encased in visored motorcycle helmets. About all that is missing is the concept of the internet and the virtual realm existing in cyberspace, neither of which were around in the real world at the time – the film only offers a single brief venture into the world of the simulation, something you would never get away with in a Virtual Reality film today. World on a Wire also predates the advent of the home computer and so everything takes place inside vast mainframes in corporate buildings. One novel technological touch that Fassbinder adds is the use of tv phones – albeit where the phones are bulky desktop units the size of modern computer CPUs. There is the odd part that has dated today – such as when the film registers shock at the notion of a research institute getting into bed with a corporation when nowadays the idea seems so run of the mill it would not even curl an eyebrow.

The enormous surprise about World on a Wire is how sophisticated its use of Virtual Reality themes are. You only need contrast it to The Thirteenth Floor, which played entirely by the books of cliches, whereas World on a Wire adeptly avoids them even though they have not yet been set in place. What is going on is structured as a unfolding mystery – the security head (Ivan Desny) who disappears at a party with the hero then finding that nobody can remember anything about his existence; the new security head (Joachim Hansen) insisting he always held that role and that Klaus Löwitsch has dined with him and his wife, even though Löwitsch has not met them before; Löwitsch entering the simulation and being jolted to see the missing man there. One comes to World on a Wire after seeing far too many other Virtual Reality films for the revelation that the world we are in is a simulation to be a surprise – nevertheless, you can only imagine what a wild, left field reversal it would have been back in the day the film was made.

Not only was World on a Wire the first Virtual Reality film, it was the first film in the Philip K. Dick model. While the first half of the series is about introducing the concept of simulation, the second half creates a growing sense of paranoia as Klaus Löwitsch realises that the whole world is simulated and in his attempts to find the enigmatic controllers in the level above at the same time as they try to eliminate him. All of this is cleverly written in terms of swinging uncertainty between whether Klaus Löwitsch is going mad or everything around him is part of a virtual simulation.

Fassbinder directs some fascinatingly oblique scenes – like a scene where Klaus Löwitsch is walking along a street and a crane holding a pallet of concrete blocks follows, halts above him as he stops to ask a woman for a light, only for her to be crushed by the falling blocks and then for Löwitsch with supreme casualness to light his cigarette from the lighter in her dead hand and continue on. The film also attempts to philosophically examine the idea of simulation with Löwitsch making some striking analogies that compare the situation to Aristotle and Descartes. These scenes hold an intelligence of writing and sophistication of ideas that The Thirteenth Floor seemed to miss altogether.

Fassbinder directs with a deliberately alienating modernism. The musical score is an often interesting combination of early electronic music. As was the prevailing trend in the early 1970s, the future was seen as filled with white antiseptic walls and plastic vacuform furniture – see the likes of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), The Andromeda Strain (1971), THX 1138 (1971). Fassbinder achieves this with great economy by shooting in malls in Paris and Munich. In the interiors, he suggests a bored decadence – parties where the dressings are 70s ultra-modernism and people swim indoors; Klaus Löwitsch having conversations as the louche demimondes of the future stand about and blankly stare at him; or a party in a library basement filled with topless women and well-muscled bare-chested Black men dancing. People often sit staring blankly into the distance as though Fassbinder is subtly cluing us in that they are merely automatons in the simulation. One of the more fascinating elements is how Fassbinder is perpetually placing mirrors around the characters – having people seen in multiple reflections or talking to others while reflected in mirrors – as though to echo the principal theme of simulation and replication. This is something that becomes more pronounced as the hero gains increasing awareness of the virtual world.