UK. 2002.

Crew

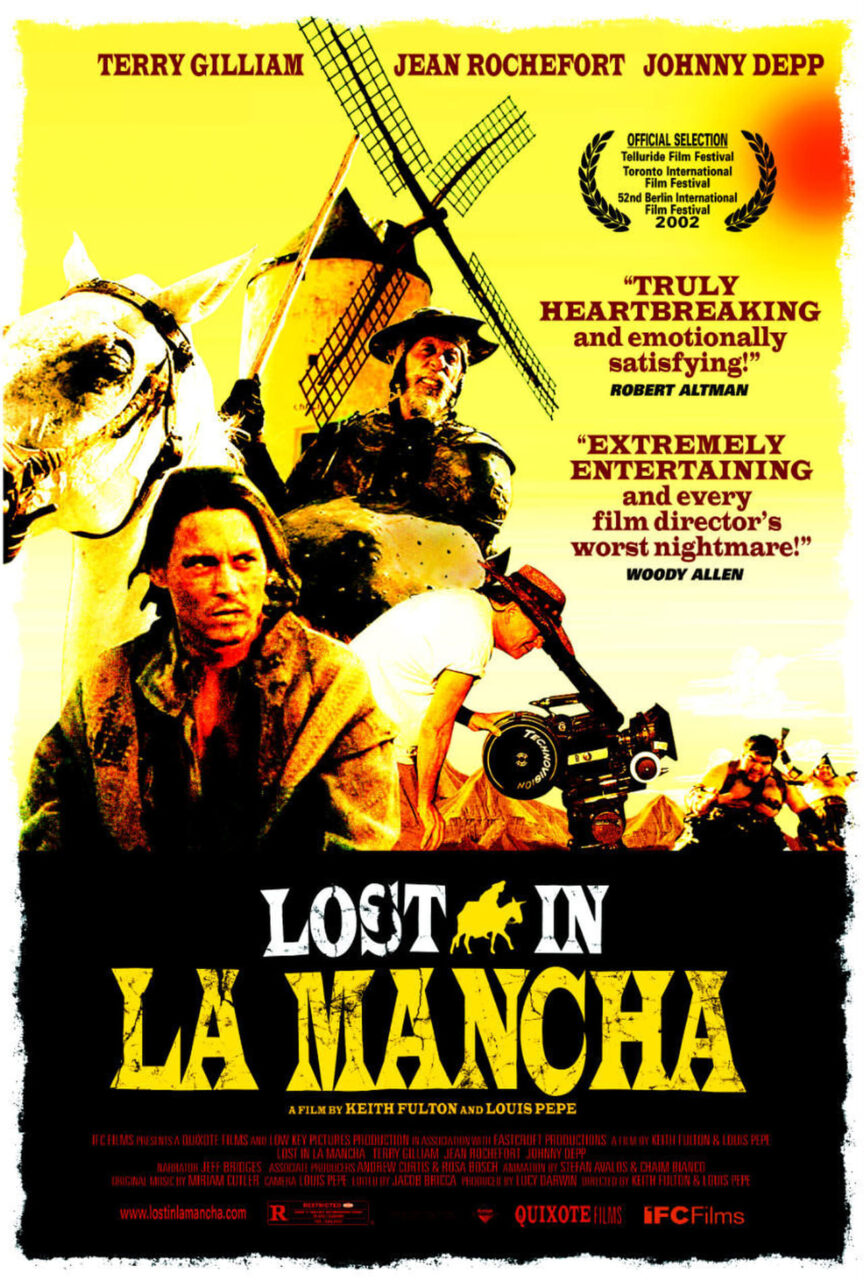

Directors – Keith Fulton & Louis Pepe, Producer – Lucy Darwin, Photography – Louis Pepe, Music – Miriam Cutler, Production Design – Benjamin Fernandez. Production Company – Quixote Films/Low Key Productions.

Making Of documentaries are routinely released as tv filler and come accompanying almost any standard big-budget cinema release these days, are indeed obligatory with the rise of the DVD extras market. Most are bland, forgettable pieces of PR spin that offer nothing in the way of behind-the-scenes gossip, filmmaking secrets, or do anything other than act as a half-hour commercial for the film in question. It is rare when Making Of documentaries take on a life of their own and offer genuine depictions of problematic productions gone wrong. Les Blank’s Burden of Dreams (1982), concerning the making of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982), was one such occasion, as also was Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991) concerning the making of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) and Full Tilt Boogie (1997) about the making of From Dusk Till Dawn (1996). Subsequently this has taken off as a genre and we have had Despite the Gods (2012), Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013), Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau (2014), The Death of “Superman Lives”: What Happened? (2015), Doomed: The Untold Story of Roger Corman’s The Fantastic Four (2015) and George A. Romero’s Resident Evil (2025) documenting other ill-fated productions. Another such occasion was Lost in La Mancha, which set out as a standard Making Of featurette, before the filmmakers unwittingly realised they were capturing a disaster transpiring around them.

The film in this case was Terry Gilliam’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. Terry Gilliam was of course one of the core members of the Monty Python troupe before he branched out as a highly individualistic director with films such as Jabberwocky (1977), Time Bandits (1981), Brazil (1985), The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1989), The Fisher King (1991), Twelve Monkeys (1995), Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), The Brothers Grimm (2005), Tideland (2005), The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009) and The Zero Theorem (2013).

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote was a project that Terry Gilliam had nurtured for the better part of ten years. He finally managed to launch his production in 2000 to be shot in Madrid. As a director, Terry Gilliam had developed a reputation as a maverick who was irresponsible with his budgets, largely due to the problems that overran and nearly sank Baron Munchausen. As a result, Gilliam found difficulty in raising the capital in the US and instead launched the production with pan-European funding, but as a result ended up going into the production with a $31.4 million budget, far less than what was needed.

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote was an extraordinarily ambitious project – casting included Johnny Depp, Ian Holm and Vanessa Paradis. Lost in La Mancha takes us on a tour through elaborate mock-ups of giant hands, the costume shops and armies of mannequins that were constructed for the film. Equally so, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote was a uniquely Gilliam-esque story – the film was not merely an adaptation of Miguel Cervantes’ perennial story but also had a wraparound wherein Johnny Depp played a time-travelling ad exec named Tony Grisoni (who in a curiously meta-fictional touch is named after Terry Gilliam’s regular collaborator and co-writer of the film).

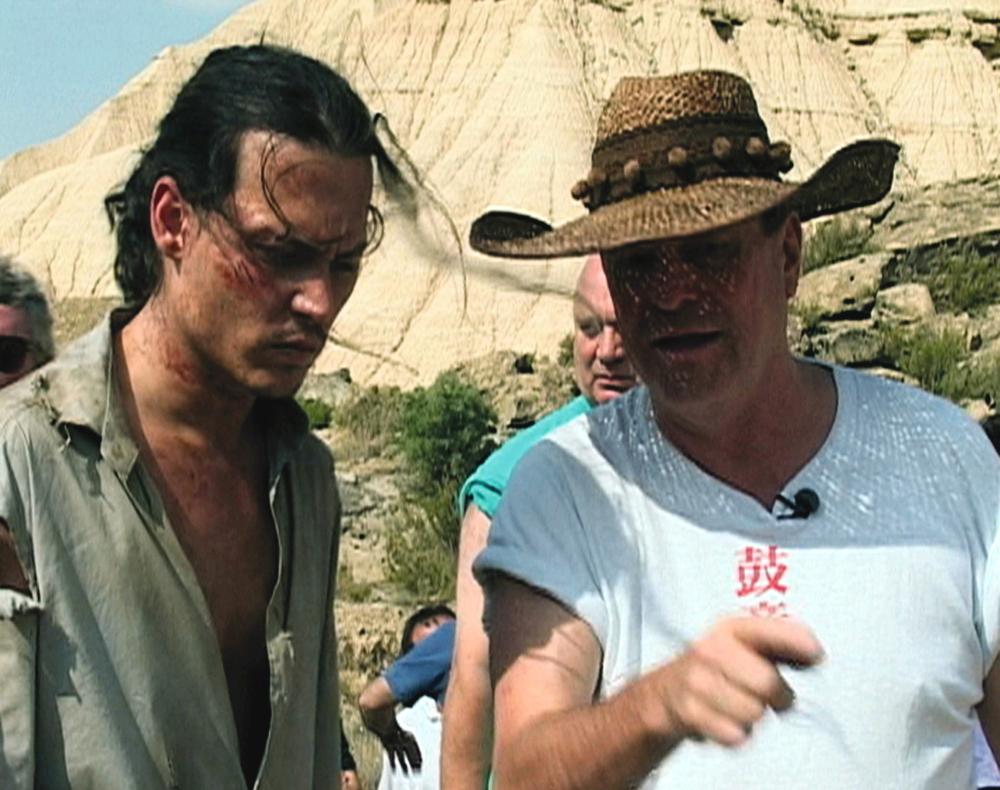

The production seemed to go bottom-up from the moment the documentary-makers arrived on the set. Lost in La Mancha charts the move from the enthusiasm with which everybody enters the production, determined to sweep on past the problems, to the extraordinary range of disasters that then started happening – the problems in simply trying to get the principal actors to come for costume fittings, even not knowing whether the stars were going to turn up; to shooting beginning, only to find that nobody had bothered rehearsing the extras; the first location happening to be right next to a NATO bombing range where filming was interrupted by frequent flyovers; a freak storm washing away equipment; lead actor Jean Rochefort, who had spent some eight months learning English for the role, developing health problems, resulting in his being in excruciating agony every time he had to mount a horse and necessitating the shutting down of the production for several months to wait for him to regain his health.

Even something as small as trying to arrange a day’s shooting to make things look good for visiting investors, in a scene with Johnny Depp being knocked into a river by a horse as he struggles with a trout, is seen failing to go right through the horse’s refusal to do what it has been trained to do. The production was eventually shut down after several months of waiting on Jean Rochefort to be medically cleared. The insurance company faced the biggest-ever payout on a collapsed film project. In the end, only around three minutes of completed film were ever placed in the can.

Inevitable comparisons are made throughout the documentary between The Man Who Killed Don Quixote and Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Baron Munchausen, another disaster-laden production that contrarily did end up being completed and released. Baron Munchausen was as an equally out-of-control production with its budget doubling during shooting, Gilliam having immense problems with unreliable European producers, locations, sets and contracted stars dropping out. Both productions were also independently financed and the most expensive film ever made in Europe at the time. (Assistant director Phillip Patterson goes some way in trying to correct Terry Gilliam’s reputation as being an out-of-control director who is irresponsible with his budgets as a result of Baron Munchausen – although this is something that Lost in La Mancha is unlikely to correct anywhat). Indeed, there are a number of uncanny similarities between The Man Who Killed Don Quixote and Baron Munchausen thematically – both feature an old man who lives on improbable tall tales of heroism who sets forth on an adventure based on these notions. Jean Rochefort’s Don Quixote even has the same bony, aristocratic features that John Neville did in Baron Munchausen.

At one point in the film, Gilliam pertinently says that Don Quixote is a figure that had lain under all his work and you can see this. Figures of naive heroes on foolhardy quests driven by visions of heroic idealism and myth regularly feature in all Terry Gilliam’s works and often have their wings painfully clipped – see the likes of Jabberwocky, Brazil, Baron Munchausen and The Fisher King. Indeed, punctured heroism could be seen as the connecting theme of almost all of Terry Gilliam’s films. Equally, Cervantes’ trompe l’oeil imagery of windmills as monsters and the like also features in Gilliam films such as Brazil and The Fisher King. There is also the recurring thing that Gilliam has with giants – see Time Bandits, Brazil and Baron Munchausen.

Even more pertinent is when screenwriter Tony Grisoni compares Terry Gilliam to the character of Don Quixote himself. While on one level Lost in La Mancha is about the making of a film of Don Quixote, on another it can also be read about the Quixotic urge. What the documentary makes clear is that The Man Who Killed Don Quixote was a film driven by one person’s extraordinary creative vision. As Gilliam says, he made the film in his head for the better part of ten years and we get glimpses of it – the elaborately worked-out storyboards on show, even rehearsals where Gilliam plays the voices of all the characters. We see Gilliam’s affable certainty and optimism lighting up the production and carrying all those around him over the initial obstacles and problems. The most pertinent scene in the film is where Gilliam tries to impart his vision to production designer Benjamin Fernandez and Fernandez scratches his head in confusion, making a comment about how he cannot keep up with someone who lives on another creative level altogether.

The uncompromising nature of Terry Gilliam’s vision is something that is noted by others a couple of times. One thing you keep wondering is that, aside from the pay-or-play deal the production had with Jean Rochefort’s involvement, why the filmmakers could, for instance, not have attempted to salvage the production by recasting Jean Rochefort rather than clinging to Gilliam’s insistence that only Rochefort could play Don Quixote and forcing the wait for his return to drag out for months. Surely the broken contractual obligation to the backers in regard to Rochefort’s pay-or-play deal would have been far outweighed by the collapse of the entire production?.

It is sad to see Gilliam throughout the course of Lost in La Mancha go from someone whose optimism and abundantly overflowing creative vision enlivens everyone around him to a person who, through no real fault of his own, is reduced to holding his head in his hands in frustration at each fresh new disaster. To Gilliam’s credit, we never see any bitterness, bad temperedness or angry finger pointing, even during the production’s worst points. To his credit, Gilliam insisted that directors Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe keep filming no matter what, even when things started to go wrong, on the grounds that at least someone should be able to get a film out of the ordeal.

At one point, Lost in La Mancha shows a brief clip from Orson Welles’s attempt to film Don Quixote between 1957 and 1972, which eventually fell apart in much the same way as Gilliam’s film did. In doing so, Lost in La Mancha unwittingly reveals the truth about brilliant auteurist filmmakers such as Gilliam and Welles, who was also notorious for his problem-ridden and uncompleted projects, as well as other great filmmakers such as Stanley Kubrick and the aforementioned Francis Ford Coppola and Werner Herzog, all of whom had histories of problematic and runaway productions in furtherance of their artistic vision. The truth would seem to be that such an intensive and articulate creative vision that these people possess is always at war with mundane realities such as financiers who get scared at the notions of budget overruns, on-set-disasters and simply those of mundane imagination who cannot always see the vision the artist is trying to communicate.

Lost in La Mancha is the portrait of how such an artistic tug of war goes on, of how optimism and sheer exuberance alone was not quite adequate enough to carry the project over the disasters and hurdles that befell it and stop an extraordinary and fabulous dream from crashing and burning. As the briefly completed moments of film on display and the glimpses inside the production show, the finished version of The Man Who Killed Don Quixote would have been fabulous. It is a sad case of the mundane reality triumphing over a glorious dream, one that the world would undoubtedly have been richer off for had it been allowed its fruition. But then such punctured dreams are the essence of what Terry Gilliam’s bittersweet work, and indeed the very story of Don Quixote, is all about. It seems ironically appropriate.

Over the next decade, Terry Gilliam made noises about reviving The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. At one point, this went ahead for a projected 2011 release date starring Robert Duvall in the Jean Rochefort role and with Ewan McGregor substituting for Johnny Depp. However, with a run of bad luck that seemed even worse than the Biblical Job, financing collapsed on this in 2010 just before Gilliam went to camera. A subsequent attempt to revive the film in 2016 with John Hurt as Don Quixote ran into more finance problems and Gilliam sparring with producer Paulo Branco. Gilliam finally managed to complete the film with The Man Who Killed Don Quixote (2018) with Jonathan Pryce as Don Quixote and Adam Driver in the Johnny Depp role, although even then Branco attempted to legally prevent the film’s release, claiming he owned the copyright.

Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe subsequently went onto direct Brothers of the Head (2005), a drama about Siamese twins from a novel by SF writer Brian Aldiss. Notedly, this comes with a script from The Man Who Killed Don Quixote‘s Tony Grisoni. They subsequently reunited with Terry Gilliam for He Dreams of Giants (2019), a documentary about his completed version of the film.

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 2002 list).

Trailer here