USA. 2014.

Crew

Director – David Gregory, Producers – John Cregan, Carl Daft & David Gregory, Photography – Jim Kunz, Music – Mark Raskin. Production Company – Severin Films.

Cast

Fairuza Balk, Hugh Dickson, Oli Dickson, Peter Elliott, Michael Gingold, Marco Hofschneider, David Hudson, Graham Humphreys, Kier-La Janisse, Paul Katte, Fiona Mahl, Rob Morrow, Edward R. Pressman, James Sbardellati, Robert Shaye, Richard Stanley, Tim Sullivan, Graham ‘Grace’ Walker

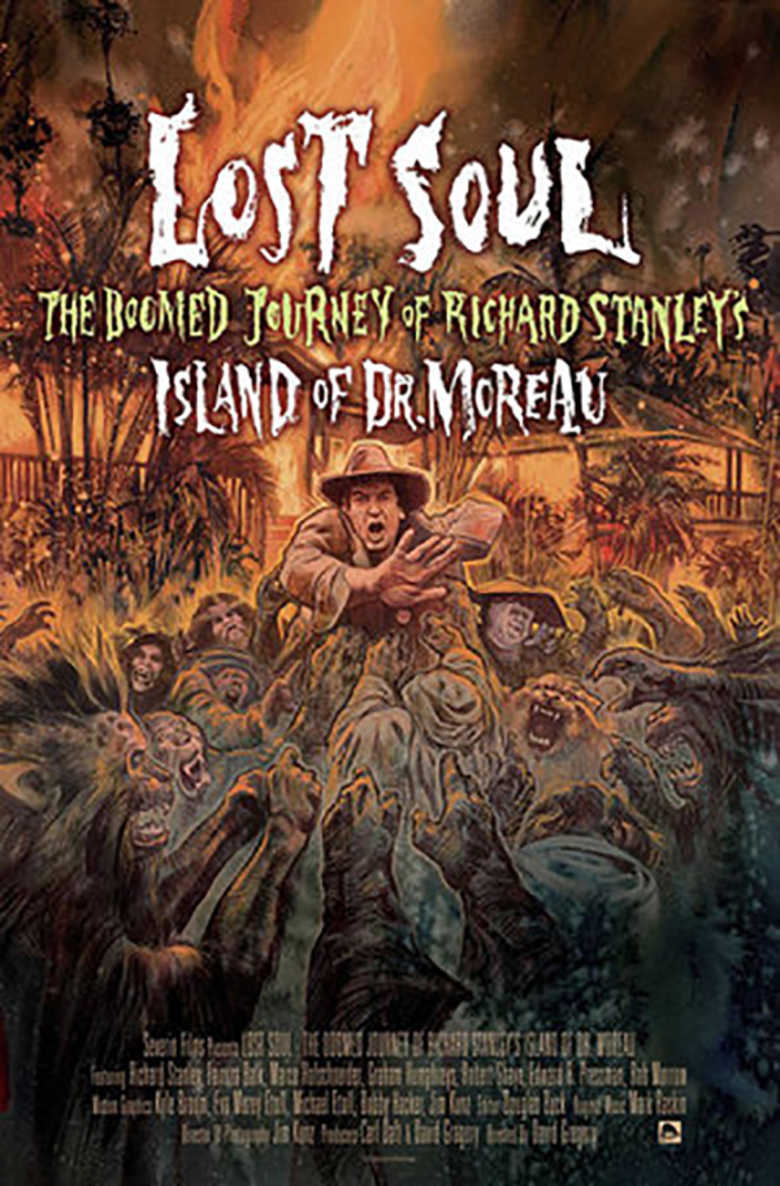

Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau is another in the burgeoning industry of cinephilia – documentaries about disaster-laden films and/or projects that never saw the light of day. There have been the likes of Burden of Dreams (1982), concerning the making of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982); Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991) about the making of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979); and Lost in La Mancha (2002) about the failure of Terry Gilliam’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote project. The one good thing about the modern Kickstater era is that it has made it easier for people to get funding to make such projects and we recently saw Despite the Gods (2012) about the problems behind Jennifer Lynch’s Hisss (2010), Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013), The Death of “Superman Lives”: What Happened? (2015) about Tim Burton’s failed Superman Lives with Nicolas Cage, Doomed: The Untold Story of Roger Corman’s The Fantastic Four (2015) and George A. Romero’s Resident Evil (2025). In this case, Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau is centred around the New Line Cinema production of The Island of Dr Moreau (1996).

Lost Soul comes from director David Gregory, who had previously made Plague Town (2008), along with dozens of making of shorts for dvd extras of releases of genre films. Gregory was a producer and directed one of the segments on the multi-director horror anthology The Theatre Bizarre (2011) for which he had recruited Richard Stanley as director of the episode The Mother of Toads. During travels to Stanley’s home in Montesegur, France, Gregory had occasion to ask Stanley what really happened on the set of The Island Dr. Moreau and said that the story he heard was a wild and fascinating one that kept him enrapt for hours. He eventually decided that this had the makings of a documentary. Gregory later acted as a producer on Richard Stanley’s return to the director’s chair with Color Out of Space (2019) and directed further feature-length genre documentaries with Blood and Flesh: The Reel Life and Ghastly Death of Al Adamson (2019), Tales of the Uncanny: The Ultimate Survey of Anthology Horror (2020), Enter the Clones of Bruce (2023), Taste the Blood of Martin (2023) and Suzzanna: The Queen of Black Magic (2024), while he also produced Woodland Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror (2021) and Birdemic 3 – Sea Eagle (2022).

South African-born director Richard Stanley was a hot and rising name in the 1990s on the back of the cyberpunk film Hardware (1990) and to a lesser extent Dust Devil (1992), although this was plagued with copyright and distribution problems and not widely seen. Stanley recounts how he was a fan of the original H.G. Wells novel The Island of Dr Moreau (1896). He takes us through the previous film versions The Island of Lost Souls (1932), which was hated by Wells, and The Island of Dr Moreau (1977), which he saw as a child, feeling disappointed that he never got to see the Panther Girl transform. Stanley even makes mention of the unofficial Filipino productions Terror is a Man (1959) and The Twilight People (1972).

New Line bankrolled Stanley for what was initially a $35 million production, something that was soon to balloon with the signing on of names like Marlon Brando and Val Kilmer. Stanley recounts how New Line was initially reluctant to give the reins of a large production to someone who was still considered a maverick director but did so after Brando was insistent that Stanley remain in charge if he was to come on board. Sets were built in a remote area of Cairns in Queensland on the very north-eastern tip of Australia. Extensive creature effects were constructed by the Stan Winston Studio.

Richard Stanley’s initial vision of The Island of Dr Moreau seems mind-boggling – not to mention is a world away in creative vision from what it is that we eventually ended up with. He shows us artwork and describes several scenes that show a sensational wildness – scenes where the dog people pursue and kill the cat lady, cook her (because they have become civilised) and eat her but as the hero goes to kill them for it are unable to remember doing so because they have short memory spans. Other scenes with the animals taking drugs; Pendrick living among the animal people and having sex with them, including a pig lady who bites off his dick and the cat lady who it would be revealed would have six nipples and a pubic bush that grew all the way up her body; artwork of dog people acting as surgeons. Based on what we see here (and the imaginative flair that Richard Stanley has shown in his other films), you are quite certain that his Island of Dr. Moreau would have become a genre classic; instead, what we ended up with could be called a cinematic train wreck.

There seem to be numerous reasons why Dr. Moreau went astray. Most of this would appear to centre around the personalities involved. At the outset, the major difficulty was Val Kilmer who at that time was a hot star name. (This is something that rapidly plummeted in the next couple of years due to the widespread stories from Batman Forever (1995) and Dr. Moreau of how difficult Kilmer was to deal with – as a result, he largely disappeared as a leading name with any marquee power from 2000 onwards).

Stanley and others recount stories of Kilmer’s attitude and difficulty – how he would interfere with the staging of shots that had already been extensively storyboarded; how he would sit behind instead of in front of the camera; how he wanted the cutting of scenes in which another character had the substance of screen time; the subsequent conflicts of ego between Kilmer and Marlon Brando with either refusing to emerge from their trailer before the other did, or how he demanded 40% less screen time, which Stanley dealt with by getting him to swap lead roles and take the lesser part of Montgomery. There was also Marlon Brando whose daughter had committed suicide and had walked off set on another film, shutting down production altogether, forcing Stanley to have to shoot scenes around his absence, not knowing if Brando would be arriving at all.

There seems some effort to paint Richard Stanley as unstable. New Line CEO Robert Shaye cites supposed evidence such as Stanley asking for four sugars in his coffee, while production designer Graham ‘Grace’ Walker refers to Stanley arriving in Australia dressed in a white suit and carrying only a single carpetbag of personal items. Clearly, none of these have people hung around many creative types who can be classified as downright eccentric – these seem exceedingly mild examples to cite as evidence of instability.

Certainly, when interviewed, Stanley comes across as literate and intelligent. Mind you, there are times when he doesn’t exactly do his own credibility too good with lines like: “Considering the odds against me, I decided to resort to witchcraft.” From what others state, problems on the set seemed to be exacerbated by Stanley’s policy of conflict avoidance where he preferred to deliver instructions from his rented home rather than attend production meetings or else was very vague in his directions.

The crucial issue that turned the production on its head was when a hurricane struck, obliterating one of the main sets. Production was shut down. Rob Morrow recounts how he called his agent, begging to be released. (His part was recast with David Thewlis who notedly has declined to be interviewed for Lost Soul – as also has a prominently absent Val Kilmer). New Line executives dealt with this by deciding to fire Richard Stanley and hiring the late John Frankenheimer to take over the director’s chair.

John Frankenheimer was an acclaimed name in the 1960s with strong works like Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Seven Days in May (1964) and Seconds (1966). Frankenheimer’s rising star in the 1960s had faded throughout the 1970s and certainly into the 1980s. His personal assistant James Sbardellati recounts that Frankenheimer was not that interested in the project and demanded a high price, thinking that New Line would not accede. To all accounts, Frankenheimer was a hard-headed pragmatist and tough on his crew. The other interesting thing is that he would seem to be uninterested in style or message, just focused on story – which, if this is true, shows that between his work in the 1960s he had slid into an indifference about the product he was turning out. (Mindedly, he did subsequently go onto make the fine Ronin (1998), which showed he still had what it took).

All of this seemed to add up to a recipe for disaster, at which point Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau starts to become even more unbelievable and entertaining. As various production personnel recount, there was conflict between Kilmer’s ego, Brando’s ego, and Frankenheimer tearing his hair out trying to keep control of a production that was running out of control. Brando characteristically had not read the script – instead had the lines read to him by an assistant through a radio earpiece (one that kept picking up police frequencies) – and kept coming up with completely wacky elements that he insisted be written in. Fairuza Balk recounts seeing him first turn up on set wrapped in cheesecloth and in kabuki makeup, which he insisted was to protect him from the sun and was duly incorporated into the script. The enormously overweight Brando was also having heat issues and demanded that an ice bucket be made to fit onto his head, which led to a scene where Fairuza Bulk pours ice cubes into it.

Marco Hofschneider talks about Brando’s infatuation with 2 foot 4.25 inch Nelson de la Rosa who was then the world’s smallest man, and how Brando demanded that he become what others refer to his Mini-Me and have scenes tailored for him. And then there are side-splitting accounts about how completely whackadoodle Brando was. Fairuza Balk tells how she asked him to rehearse a scene and work out where their characters were coming from and he shrugged and said to her “why does it matter, why does any of it matter.” Sbardellati recounts the side-splitting story of how Brando abruptly asked that the vehicle that he and Frankenheimer were in to pull over so that they could call New Line Cinema management just to “fuck with them” or wanted elements added to the script where Moreau would wear a hat throughout and take it off at the end to reveal the head of a porpoise.

Oh and then there was Stanley – I had long thought that this story was a wild rumour but he and several of the other crew confirm it – who had neglected to board the plane flight out of Australia that New Line had booked for him and went native, living on the land. After encountering several of the film crew, they decided to sneak him back onto the set disguised under one of the Beast People masks and he stayed there for much of the production – we even see a still frame from one of the shots that ended up on screen in the final cut.

I have always maintained that the finished version of The Island of Dr Moreau was far better than its train wreck reputation and classic turkey status has it – it is often the case in films where legendary stories of disaster and star ego overshadow a production, allowing it to be perceived that way rather than on its own merits if one were to know nothing about it. There is also no question though that Stanley would have made a far better film.

The saddest casualty of the entire fiasco was Richard Stanley himself. As he sadly states, after he was fired, nobody, not even his own agent, would return his phone calls. He became essentially unemployable in Hollywood and retreated to live in a remote French village. Others speculate he was so badly damaged that he lost the confidence to get in front of a camera again. This is not quite true – he has directed three documentaries and episodes of the horror anthology The Theatre Bizarre, although no feature films up until a triumphant return with Color Out of Space (2019). As several people recount at the start, I am of the view that Richard Stanley is an enormously underrated talent. I wish that someone somewhere would give him more money (or whatever therapy he needs to regain his loss of self-confidence) to get back behind the camera again. The hope might be that the acclaim going to Lost Soul as it does the cinematic rounds is such that it revives Stanley’s name.

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 2014 list).

Trailer here