USA/France. 2013.

Crew

Director – Frank Pavich, Producers – Frank Pavich, Stephen Scarlata & Travis Stevens, Photography – David Cavallo, Music – Kurt Stenzel, Animation – Syd Garon. Production Company – City Films/Snowfort Pictures/Camera One/Endless Picnic.

With

Alejandro Jodorowsky, Devin Faraci, Chris Foss, H.R. Giger, Brontis Jodorowsky, Gary Kurtz, Diane O’Bannon, Amanda Lear, Drew McWeeny, Nicolas Winding Refn, Michel Seydoux, Richard Stanley, Christian Vander, Jean-Pierre Vignau

The Making Of film used to be a tv special, at best something designed for accompanying dvd extras. In more recent years, it has become a film entity in its own right. Of great fascination have been those films dealing enormously problem-laden production such as Burden of Dreams (1982), concerning the making of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982); Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991) about the making of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979); Lost in La Mancha (2002) about the failure of Terry Gilliam’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote project; Despite the Gods (2012) about the problems behind Jennifer Lynch’s Hisss (2010); Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau (2014); The Death of “Superman Lives”: What Happened? (2015) about the aborted Tim Burton-Nicolas Cage Superman film Superman Lives; Doomed: The Untold Story of Roger Corman’s The Fantastic Four (2015) and George A. Romero’s Resident Evil (2025). Jodorowsky’s Dune is another of these and gives a glimpse into an amazing work that never saw the light of camera – an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965) that was planned between 1974 and 1976 by cult Chilean director Alejandro Jodorowsky.

In the 1970s, Jodorowsky was at the height of his acclaim, having directed the incredibly strange Zen surrealist Western El Topo (1970) whose bizarreness caused it to become a cult midnight item. Jodorowsky was given financing to make the even stranger The Holy Mountain (1973). In these, Jodorowsky is clearly a director who regards cinema as akin to the way that the era regarded LSD and magic mushrooms – something that will break audiences out of their modes of thinking and into transcendental states. When asked what project he wanted to take on next by producer Michel Seydoux, Jodorowsky said Dune – even though he had never read the book, only went on a description of it given by a friend. It is clear though that Dune, with its messianic hero, its story about a new drug opening up the doors of perception and allowing the overthrowing of a corrupt political order, had a good deal of appeal to Jodorowsky’s interests.

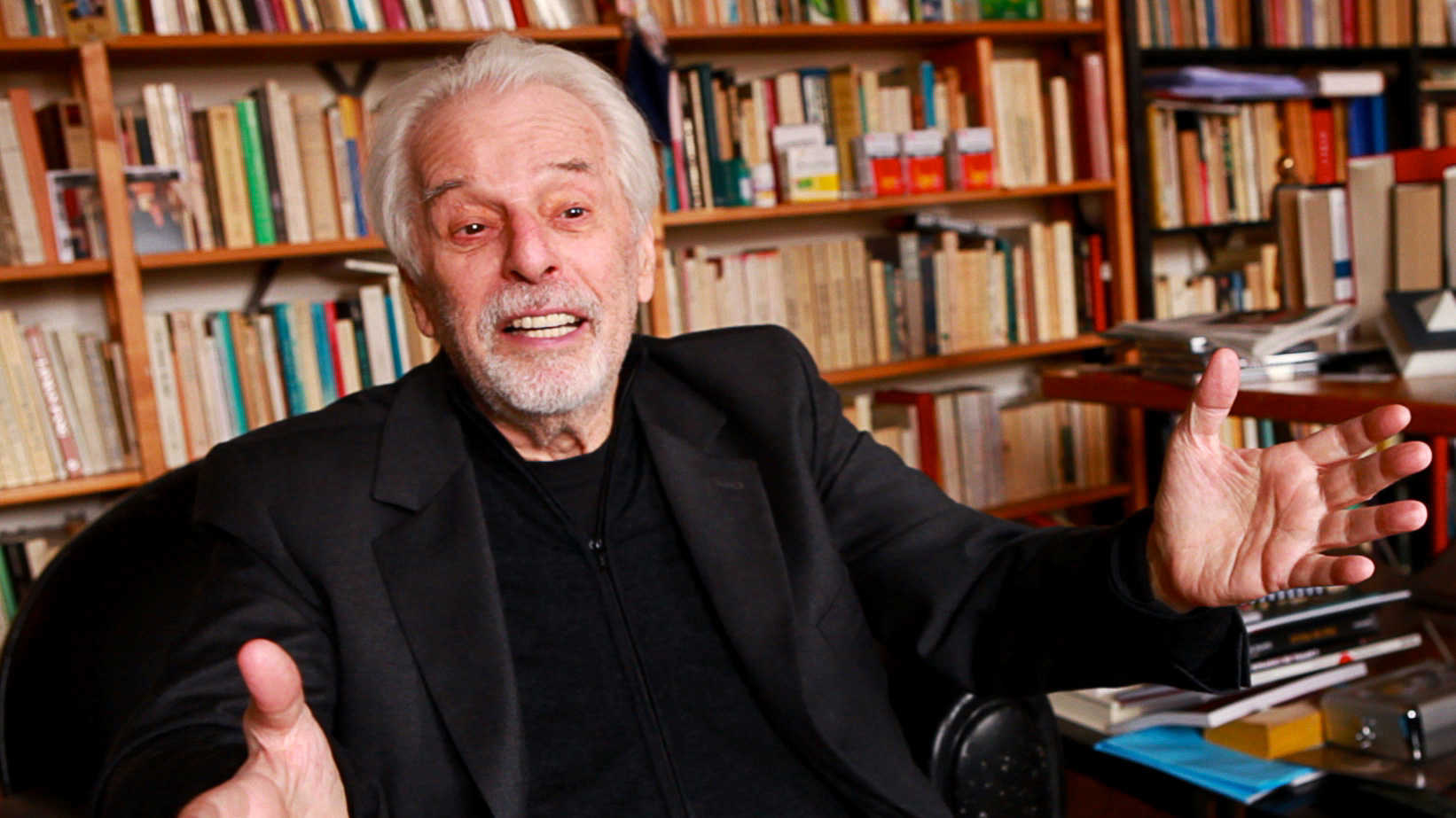

The impression you get of Jodorowsky from his films and in published interviews makes him seem a complete madman; the surprise is that he comes across as such a charming and genial figure in the interviews that make up the film. As a director, Jodorowsky is more akin to an alchemist than a storyteller or a dramatist. He keeps piling on surrealistic effect in the hope that it will create a transcendental breakthrough in ways of thinking for his audiences. To this extent, I had always thought that Jodorowsky and Frank Herbert were mismatched talents. Jodorowsky’s other works of science-fiction – comic-books such as The Incal (1981-9) and The Metabarons (1992-2003) – embody concepts taken from tarot, metaphysics and Jungian psychology rather than science. In other words, Jodorowsky doesn’t appear to be approaching Dune from the science-fictional perspective that Frank Herbert did.

Frank Herbert was never a mystic or a transcendentalist – while his characters took drugs that produced radical shifts in understanding, he always kept the essence of these visions and the nature of the experience undergone off the plotted page. Rather his story was more like an historical work, a sprawling saga about politics of empire, religion and the fight for resources. (On the other hand, Jodorowsky does give the appearance of being more familiar with science-fiction than one suspected – he after all had a familiarity with science-fiction artist Chris Foss and discovered Jean Giraud after reading Metal Hurlant).

Jodorowsky gives the impression he has merely regarded Herbert as a text to freely rework. During the interviews, he blithely claims “It is every artist’s duty to destroy the book” and then goes on to make an eye-opening metaphor for the process of adaptation as being akin to a groom tearing open his wife’s wedding dress to “rape the bride.” Some of the radical changes are evident from glimpses of the film that we are given – the Emperor having an identical replica of himself created (which was to be made from a lifemold of Salvador Dali and would appear to been to get around Dali’s desire to be paid $100,000 per minute of screen time). Duke Leto would have been a eunuch and Jodorowsky talks of a scene where Lady Jessica is impregnated and gives birth from a single drop of his blood (the storyboarded scene would have actually followed the trail of the drop of blood down into her womb) – no equivalent of any of this appearing in the book. The film would also have ended with a scene where Paul is killed, then becomes a universal spirit where every character in the film chants “I am Paul”, before the planet Arrakis is transubstantiated into spirit and moves through the universe.

Perhaps one of the most fascinating aspects of the film is Jodorowsky’s ‘warriors’ – the creative team he assembled to bring Dune to life. These included French graphic artist the late Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud who designed the planetary landscapes and British science-fiction artist Chris Foss who was brought in to give the spaceships individuality. The most interesting of these was H.R. Giger (who interestingly enough was recommended to Jodorowsky by Salvador Dali) who was brought in to design the Harkonnen homeworld.

For the special effects, Jodorowsky first went to Douglas Trumbull who was then considered the top effects man in Hollywood because of his work on 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – however, Jodorowsky claims he rejected Trumbull because he found him to be big-headed and obsessed with technical detail rather than interested in grasping Jodorowsky’s transcendental vision. After a screening of Dark Star (1974), Jodorowsky settled on Dan O’Bannon who had performed that film’s effects and was yet to embark on a screenwriting career with the likes of Alien (1979), Lifeforce (1985) and Total Recall (1990) and later as director of his own with Return of the Living Dead (1985). All of the warriors were assembled in Paris and began the creation of Jodorowsky’s fabled storybook – the finished version of which is several feet thick.

Even more outlandish were Jodorowsky’s casting choices. For Paul Atreides, Jodorowsky chose his own son Brontis – who as an adult bears a striking resemblance to Alec Newman who played Paul in the Dune (2000) tv mini-series – and placed him through rigorous martial arts training regime in order to prepare him spiritually for the role (something that the now middle-aged Brontis reflects on with puzzled amusement). The craziest piece of casting was Salvador Dali as the Emperor – Jodorowsky tells highly amusing stories about Dali wanting to be the highest paid actor in the world, asking cryptic questions about watches in the sand to test Jodorowsky, and demanding helicopters and the inclusion of scenes that involved burning giraffes. Or of how Jodorowsky approached Orson Welles to play Baron Harkonnen by staking out Welles’s favourite Parisian restaurant and promising to hire the waiter to tend him every day. Other fascinating pieces of casting included Mick Jagger as Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen, Dali’s companion the androgynous Amanda Lear as Princess Irulan and Jodorowsky’s amusing anecdote of the interview with David Carradine who was cast as Duke Leto.

Jodorowsky’s film would be been an amazingly extravagant production. With casual hyperbole, Jodorowsky several times throughout the documentary states that his Dune would have been “the greatest film ever made.” We see some of Moebius’s costume designs, Chris Foss’s spaceship designs and especially H.R. Giger’s work for the design of the Harkonnen homeworld that included a vast castle shaped like the Baron’s own obese body with the mouth opening up into a spaceship hangar and a stairway egress that consisted of deadly sword traps. There are even scenes where some of the storyboards have been built out as animatics, most notedly a visualisation of Jodorowsky’s amazing opening – where he admits he was trying to one-up Orson Welles’ opening from A Touch of Evil (1958) – that would have zoomed across the galaxy in a single shot, taken in pirates attacking a spice shipment to finally arrive at Arrakis.

Would Jodorowsky’s Dune have been as amazing a work as it seems? It’s hard to say – one suspects it would have emerged more akin to Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), which is either loved or hated depending on your entry point as a Kubrick or a Stephen King fan ie. that Frank Herbert fans and science-fiction purists would probably have hated the film but bizarre cinema junkies would have drunken it in. Nevertheless the enthusiasm and awe of which those closest to the creative source speak of the work imparts itself across the film. You feel for the failure of Dune as something that would have been an amazing experience.

The production fell apart from the same woes we see playing out in Lost in La Mancha – the clash between grandiose artistic vision and the insecurity of the money people. To Hollywood, Jodorowsky was an unknown, had a reputation as a wild man. Despite securing a substantial proportion of the budget, he failed to get the full amount he needed and the production fell apart just before shooting began. Jodorowsky laments how he was constrained in his own unwillingness to compromise and cut the production down to a reasonable commercial length. He remains philosophical about the film’s failure and you get the sense, seeing him thirty-five years later, that he succeeded in turning the failure around into something positive.

Rather amusing is his response to the subsequent film version Dune (1984), which he hoped would have turned out fine under David Lynch, whom he admired, and his undisguised joy at how awful the finished film was. (Not a position that this author agrees with). Subsequent to the collapse of Dune, Jodorowsky’s career has been uneven. He has made Tusk (1980) and The Rainbow Thief (1990), both of which were troubled and little seen, and most successfully Santa Sangre (1989). Ironically, the filming of Jodorowsky’s Dune proved the opportunity for he and Michel Seydoux to repair the rift and collaborate on a new film The Dance of Reality (2013).

Perhaps the film’s most specious case comes towards the end where director Frank Pavich and others try to argue that Jodorowsky’s Dune was so visionary that images from it were incorporated in numerous films subsequently including Star Wars (1977), Flash Gordon (1980), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and Prometheus (2012), citing the fact that the storyboard book was in circulation in Hollywood and no doubt inspired other directors. All one can say is perhaps. George Lucas, Ridley Scott and Steven Spielberg don’t exactly strike one as directors incapable of coming up with imaginative shots of their own and when a film comes down to comparing shots from storyboards of a never-made film, it seems a tenuous connection at best. Even worse is where critic Devin Faraci tries to draw a connection that runs from Dune to Alien (fair enough) to then saying that Alien inspired Ridley Scott to make Blade Runner (1982), which in turn inspired William Gibson and led to the creation of The Matrix (1999) by which point the connection becomes so thin as to be non-existent.

Of course, the connection that is most obvious is the Alien one, which was scripted by Dan O’Bannon. Quite clearly O’Bannon, coming straight off Dune, went and recruited much of the same creative team he worked with on Dune including Jean Giraud and, most famously, H.R. Giger, who went onto gain worldwide exposure due to the creation of the title creature.

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 2013 list).

Trailer here