Crew

Director – Martin Scorsese, Screenplay – John Logan, Based on the Novel The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick, Producers – Johnny Depp, Tim Headington, Graham King & Martin Scorsese, Photography (3D) – Robert Richardson, Music – Howard Shore, Visual Effects Supervisor – Bob Legato, Visual Effects – Lola VFX (Supervisor – Edson Williams), Matte World Digital (Supervisor – Craig Barron), Nvizage & Pixomondo (Supervisor – Ben Grossman), Special Effects Supervisor – Joss Williams, Automation Created by Dick George Creative Services, Production Design – Dante Feretti. Production Company – GK Films/Infinitum Nihil/Dear Street/Future Capital/Screen Capital.

Cast

Asa Butterfield (Hugo Cabret), Ben Kingsley (Georges Melies), Chloe Grace Moretz (Isabelle), Sacha Baron Cohen (Inspector Gustav), Helen McCrory (Mama Jeanne), Christopher Lee (Monsieur Labisse), Emily Mortimer (Lisette Ducet), Michael Stuhlbarg (Rene Tabard), Ray Winstone (Uncle Claude Cabret), Jude Law (Hugo’s Father), Frances de la Tour (Madame Emilie), Richard Griffiths (Monsieur Frick)

Plot

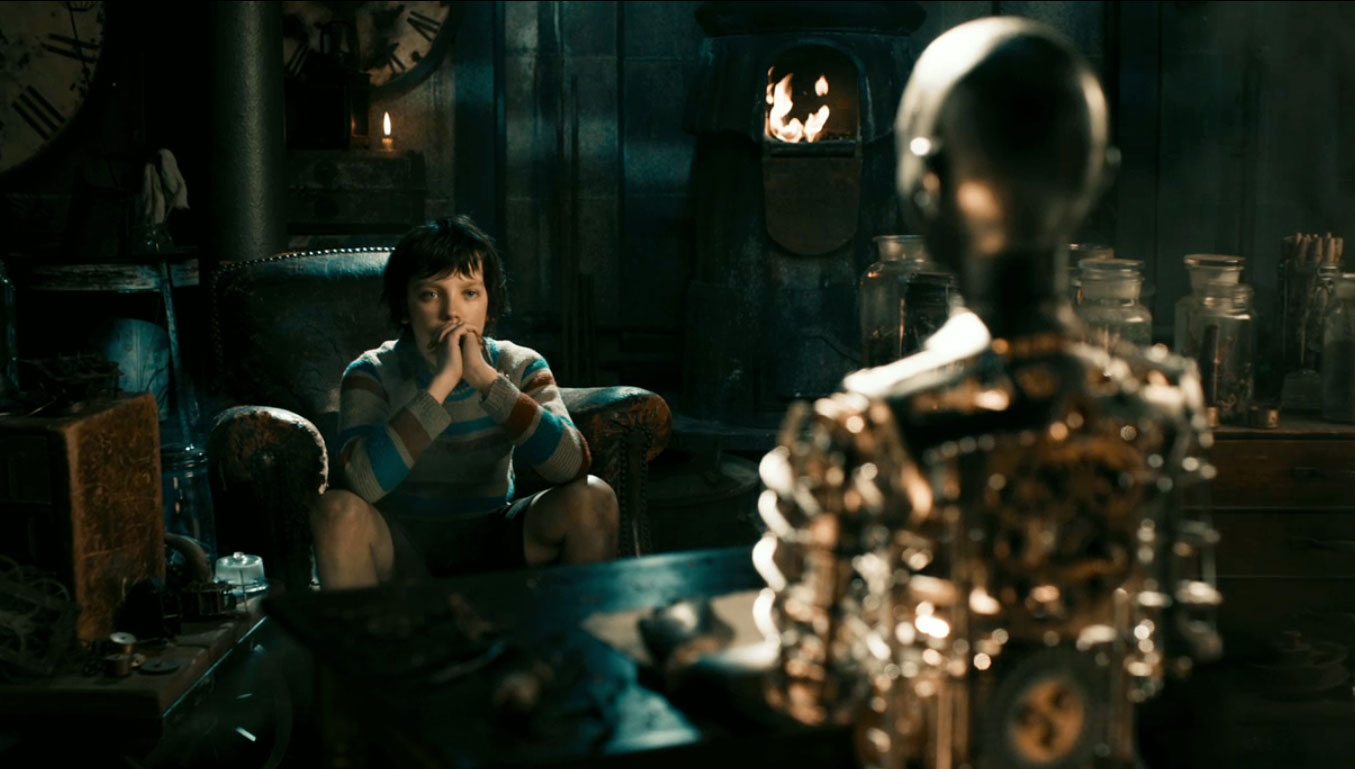

Paris, the 1930s. Young Hugo Cabret lives in the walls and basement of the Montparnasse train station. After his father died, Hugo was adopted by his drunken Uncle Claude who tended the station’s clock but his uncle has now disappeared and Hugo tends the clocks alone, surviving by stealing food from the concessions. His bane is the officious stationmaster Gustav who delights in capturing runaway children and sending them to the orphanage. Hugo is caught by Georges, the elderly man who runs a stall selling toys, after he tries to steal some of Georges’ clockwork parts. Georges confiscates Hugo’s notebook and threatens to burn it. The book contains drawings made by Hugo’s father of how to repair an automaton that he rescued from a museum. After his father’s death, Hugo has been painstakingly completing the job with foraged mechanical parts. Hugo appeals to Georges’ niece Isabelle, a young girl his own age, to help retrieve the book. Georges eventually agrees that he will allow Hugo to earn the notebook back by working for him. During their search for the notebook and the key needed to make the automaton work, Hugo and Isabelle discover her grandfather’s past as the filmmaker Georges Melies, renowned for his silent movie flights of fantasy and magic. However, this is a past that now only holds bitter memories for Georges.

Martin Scorsese is one of modern American cinema’s authentic geniuses. Ever since his appearance with Boxcar Bertha (1972), Scorsese has delivered classic after classic – Taxi Driver (1976), Raging Bull (1980), The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Goodfellas (1990), The Aviator (2004), The Departed (2006). What is also notable about Martin Scorsese’s output is the extraordinary versatility he demonstrates in being able to hop between genres. He has ventured into numerous arenas from gritty urban realism – Mean Streets (1972), Taxi Driver and Bringing Out the Dead (1999), to the musical – New York, New York (1977), music documentary – The Last Waltz (1978), No Direction Home: Bob Dylan (2005) and Shine a Light (2008), oddball comedy – The King of Comedy (1982) and After Hours (1985), the religious drama – The Last Temptation of Christ and Kundun (1997), the gangster film – Goodfellas, Casino (1995) and The Departed, the psycho-thriller – Cape Fear (1991) and Shutter Island (2010), period drama – The Age of Innocence (1993), and biopic – Raging Bull and The Aviator. There are few genres that Martin Scorsese has not touched during what begins here his fifth decade as a filmmaker. (Personally, I would love to see Scorsese touch the science-fiction genre someday just to see what he would do with it).

Hugo is Martin Scorsese’s venture into making a children’s film. In this case, he adapts The Invention of Hugo Cabret (2007), an award-winning illustrated book by Brian Selznick. Clearly, what drew Martin Scorsese to Hugo was not necessarily its’ potential as a children’s film but its dealing with cinema history – in this case, the story of early French film pioneer Georges Melies (1861-1938). Melies was originally a stage magician. He was present when the Lumiere Brothers’ screened the world’s first ever film, the one-minute long The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1896) where, as Hugo recounts, the audience genuinely believed that a train was crashing into the theatre. Melies sought to obtain his own film camera, eventually converting a projector he had purchased from England. As he embarked on a filmmaking career, Melies became the father of special effects trickery and made numerous films dependant on stop-action substitutions, double exposures and matte effects. As Hugo depicts, Melies constructed the world’s first film studio in his garden at Montreuil, built as a glass house to make use of natural lighting (the idea of artificially lit sets had not occurred at the time) and an adjoining workshop where he and his team would create elaborate sets and costumes.

Melies produced between some 500-800 films during his career, around 200 of which survive today, most being around 1-3 minutes long. The most famous of these was A Trip to the Moon (1902), which is often incorrectly called the world’s first science-fiction film. Melies’s production company collapsed in 1913, after which he destroyed the props and sold the film negatives off where the nitrate was melted down to make boot heels for the French Army during World War I. Almost all of the details that are shown regarding Georges Melies in Hugo are taken from the record, including that he attempted to build automata (which have alas been lost) and that he ended up poor and dissolute, running a booth in the Montparnasse train station in Paris during his later years, before being rediscovered and awarded the Legion d’Honneur in 1931.

Hugo has clearly been greeted by Martin Scorsese as an opportunity to explore his love of cinema history. (Scorsese had previously directed and narrated the 7½ hour tv documentary A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies (1995), as well as produced and narrated Val Lewton: The Man in the Shadows (2007) about 1940s horror producer Val Lewton). Hugo frequently becomes an opportunity for Scorsese to pay homage to the magic of early silent cinema. Aside from Georges Melies, we get tributes to and footage from other silent filmmakers/stars such as Harold Lloyd, the Lumiere Brothers, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Thomas Edison’s The Great Train Robbery (1903). Scorsese also conducts elaborate colour and 3-D restagings of scenes from and the making of Melies films such as A Trip to the Moon, Fairyland: A Kingdom of Fairies (1903), The Palace of Arabian Nights (1905) and The Eclipse: Courtship of the Sun and Moon (1907).

Even aside from that, the film recreates several film scenes during the climactic pursuit of Asa Butterfield through the station by Sacha Baron Cohen in which Scorsese manages to cinematically quote both The Arrival of a Train and Harold Lloyd’s famous clock hanging stunt from Safety Last (1923). Scorsese even stages a spectacular dream sequence where a train goes amok through the platform that reconstructs an actual derailment that occurred there in 1895 where a train ran through the station. Not unlike Woody Allen’s recent Midnight in Paris (2011), which was set in Paris only a few years earlier, Scorsese also stocks the background with cameos of famous historical personages including James Joyce, Salvador Dali and jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt.

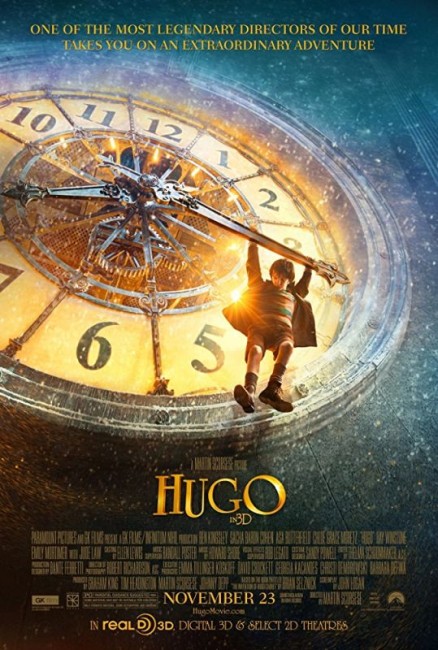

Hugo must have been a nightmare for the studio publicity department – you can see this in the promotional campaign. In pre-production, the film was announced under the full title of Brian Selznick’s book The Invention of Hugo Cabret. The successive year saw this whittled down to Hugo Cabret, with the surname then being dumped, presumably because it was too French for American audiences, to the more anonymous single name of Hugo. Even aside from that, Hugo comes with a considerable rift between what the studio publicity department is selling it as and the film you end up seeing. The trailer seems to want to pump Hugo up into being a fantasy film about a boy discovering something magical inside the train station, which you are led to believe is the automaton. Contrasted to this, Martin Scorsese wants to make an historical film about Georges Melies and the early days of silent cinema. The surprise before going into the film is that there is no mention of Georges Melies in the publicity, nor of the substantial part of Hugo that deals with the history of early film. Rather the trailer’s focus is on the escapades around the railway station and the unveiling of the automaton – the latter, while important to the story, is largely forgotten about past the halfway point. After watching Hugo, you find there is no overt fantasy element as the trailer tries to convince us – nothing magical in the train station and nothing extra-ordinary about the automaton other than what automata are traditionally supposed to do.

The problem with Hugo one suspects is that the studio were happy to hand a big-name director a purported $170 million budget, allow the construction of elaborate sets at Shepperton and the employment of a number of well-known name stars, but ended up with something that is not entirely the children’s film they expected. Certainly, it is a major stretch to believe that the intended children’s audience would have much interest in let alone knowledge of Georges Melies or the history of early silent cinema, which is what Martin Scorsese seems interested in making a film about. Indeed, what Scorsese appears to have delivered is a children’s film that is made for adults – not even ordinary adults but audiences who are clearly cineastes. All of which does leave Hugo as a decided white elephant in terms of marketable audience niches to pitch the film. Not that that prevented Hugo from doing reasonable box-office success in the Christmas 2011 season, although far from earning back its $170 million budget.

Certainly, Hugo is a beautifully made film. Martin Scorsese gets right the essential enchantment of all good children’s films. The story plays out with a considerable magic and the performances end up being heartfelt. There is maybe an overly exaggerated slapstick element when it comes to Sacha Baron Cohen’s inspector but Cohen takes the character into bizarrely amusing areas that go beyond caricature.

Hugo was also released in 3D. Ever since the massive success of Avatar (2009), 3D has become a curse that is dragging down modern cinema where studios are trying to charge overhiked prices to let a few things pop out of the screen at you, a gimmick that was ground into the dirt throughout 2010-1 by numerous films that regarded the process as nothing more than a new bandwagon to exploit. The surprise towards the end of 2011 is that we have started to see a number of respected filmmakers finally jumping aboard 3D to see what they are capable of doing with it – Tarsem Singh with Immortals (2011), Steven Spielberg with The Adventures of Tintin (2011), Werner Herzog with Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2011) and Martin Scorsese here.

Out of this, Scorsese produces something exquisite. The opening scenes as the camera moves through the station, into and around the hidden nooks and crannies has a magical effect that just shows just what filmmakers are capable of making 3D do in terms of dimensional animation if they look beyond the tiresome amusements of pop-up effects. In the end, Hugo is perhaps not another Taxi Driver or Raging Bull, but it is light years ahead of everything else being placed out there in the name of children’s entertainment.

Hugo ended up receiving eleven Academy Award nominations, including for Best Picture, Martin Scorsese for Best Director and for Best Adapted Screenplay.

2011 was the 150th anniversary of Melies’s birth and saw a number of other tribute, including Melies Cinemagician (2011) and the documentary The Extraordinary Voyage (2011) made to accompany a digital colour restoration of A Trip to the Moon. Melies even turned up not long after as a character in a French animated children’s film Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart (2013).

Martin Scorsese’s other films of genre interest are:- the urban psychosis film Taxi Driver (1976); the revenge thriller Cape Fear (1991); the urban ghost story Bringing Out the Dead (1999); and the sinister asylum psycho-thriller Shutter Island (2010). Scorsese also makes occasional acting appearances and has been in several genre films – as Vincent Van Gogh in Akira Kurosawa’s fantasy anthology Dreams (1990), as himself in Albert Brooks’s Hollywood satire The Muse (1999) and as a talking fish in the animated Shark Tale (2004). He also produced the modernised tv mini-series Frankenstein (2004), the documentary Val Lewton: The Man in the Shadows (2007) about the 1940s horror producer, the Norwegian-set serial killer thriller The Snowman (2017), Shirley (2020), a biopic of horror writer Shirley Jackson, the ghost story The Eternal Daughter (2022), and narrated/produced the documentary Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger (2024).

Screenwriter John Logan has had a number of other genre associations, including writing the scripts for Bats (1999), Star Trek: Nemesis (2002), The Time Machine (2002), Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas (2003), Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd: The Demon Fleet of Barber Street (2007), Rango (2011), the James Bond films Skyfall (2012), Spectre (2015), and Alien: Covenant (2017), as well as created the tv series Penny Dreadful (2014-6) featuring characters from Victorian horror. Elsewhere, Logan has written A-list scripts such as Any Given Sunday (1999) and The Last Samurai (2003), as well as received Academy Award nominations for Gladiator (2000) and writing Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator (2004).

(Winner for Best Production Design, Nominee for Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Supporting Actor (Ben Kingsley) and Best Cinematography at this site’s Best of 2011 Awards).