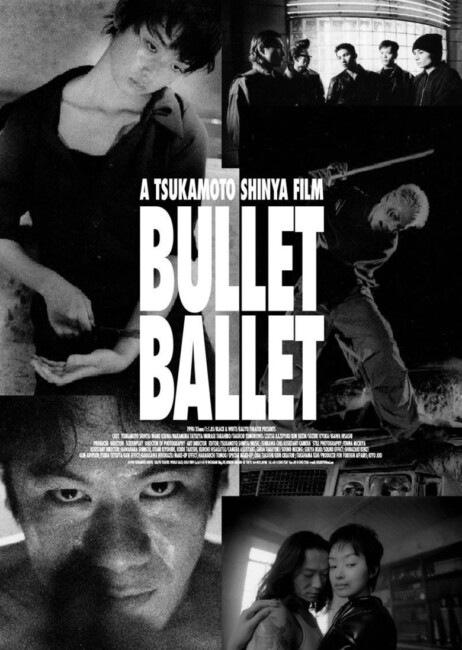

Crew

Director/Screenplay/Producer/Photography (b&w) – Shinya Tsukamoto, Music – Chu Ishikawa, Gun Effects – Hirokazu Karasawa, Makeup Effects – Tomoo Haraguchi, Special Makeup – Takashi Oda, Gun Creator – Takahama Kan. Production Company – Kaijyu Theater.

Cast

Shinya Tsukamoto (Goda), Kirina Mano (Chisato), Tatsuya Nakamura (Idei), Takahiro Murase (Goto), Kyoka Suzuki (Kiriko)

Plot

Goda, a Tokyo commercials director, is shocked upon returning to his apartment to find that his girlfriend Kiriko has committed suicide by shooting herself. He is baffled as to how she has managed to acquire a gun when ownership of firearms is prohibited in Japan. Goda then becomes obsessed with obtaining a gun, scouring the internet, trying to buy one from blackmarket dealers on the street, even trying to construct his own. At the same time, he consorts with the prostitute Chisato. When he doesn’t pay her, he runs afoul of the gang that she hangs with who beat him up. He is then approached by a foreign woman who offers him a gun if he will marry her for citizenship in return. Chisato then draws Goda into a turf war between two gangs where his possession of the gun opens up a bloodbath.

Shinya Tsukamoto made a startling appearance from nowhere with Testuo – The Iron Man (1989), an extraordinary no-budget film that showed man and machine fusing in a wild, surreal collusion of psycho-sexual and Cyberpunk imagery. Tsukamoto’s frenzied pacing created a film that leaped off the screen with an astonishing ferocity and wildness. Tsukamoto went onto make a number of other films including Hiruko the Goblin (1990); the Tetsuo remake/sequels Tetsuo II: Body Hammer (1992) and Tetsuo: The Bullet Man (2009); Tokyo Fist (1995), a film about boxing that is imbued with the same unique flesh and machinery fetishism; the twin drama Gemini (1999); A Snake of June (2002) about a woman discovering erotic pleasure via a mystery blackmailer; Vital (2004) about an amnesiac man reconstructing his life; Haze (2005) about a man trapped in an allegorical maze; Nightmare Detective (2006) and its sequel Nightmare Detective 2 (2008) about an investigator who can delve into dreams; and Kotoko (2011) about a woman suffering hallucinations.

Shinya Tsukamoto always seems to make films about repressions. His films are like single 90-minute primal screams where his protagonists seem to be crying out with a desire to force their bodies to express the inexpressible. Tsukamoto’s films are akin in many ways to the films of David Cronenberg. (The hero’s obsessive drive to find a gun in Bullet Ballet in many ways resembles the protagonists of Cronenberg’s Crash (1996) and their fetishistic desire to meld with car crashes). Like Cronenberg, Tsukamoto’s protagonists regard their flesh as a malleable alien object that is always trying to express something that they themselves cannot – be it the salaryman in Tetsuo whose clearly repressed sexuality is trying to fuse with machinery; Tokyo Fist, where the protagonists being battered in a boxing ring or pierced with metal objects becomes a wildly masochistic means of expressing pain; to Gemini where a physical duplicate of the socially respectable hero’s body (ie. a twin) embodies a social underclass he ignores and the carnal desires that he represses.

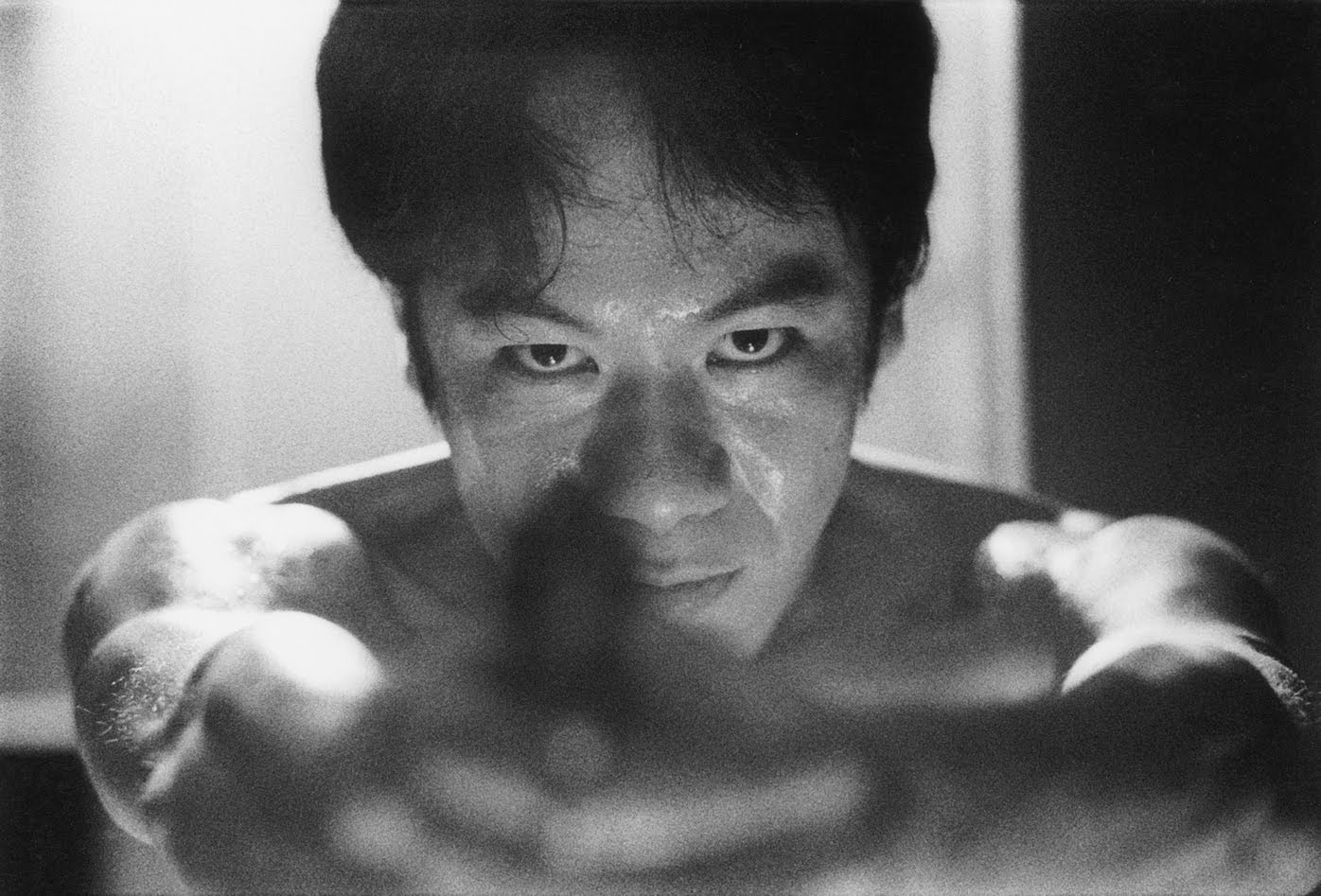

Bullet Ballet is another side to Shinya Tsukamoto’s repressions. He himself plays another of his milquetoast salarymen – one who is so caught up in his job that he doesn’t even take time off work when his girlfriend dies. His obsession with obtaining the gun is another form of bodily expression – the way the gun is fetishized here is not at all unakin to the images of the hero in Tetsuo fusing into pieces of machinery and especially Tetsuo II where characters’ arms kept metamorphosing into guns (albeit literalised here rather than on the level of surreal imagery). When the hero finally does obtain the gun, Tsukamoto’s imagery is fetishized – in a frenzied montage we see him slapping his face with it, caressing it across his body, putting the barrel in his mouth and then branding himself with a piece of metal heated on his stovetop. There is more of the insane masochism that fuelled Tokyo Fist – with Tsukamoto returning to boxing clubs and more slow-motion shots of boxers faces being pummelled. (It is not entirely clear why but the hero’s immediate reaction to his girlfriend committing suicide appears to be going and consorting with a prostitute and then not paying her so that he can get beaten up by the gang that control her, as though this is the most natural way in the world of expressing grief. Although, in that Shinya Tsukamoto’s heroes only seem able to express emotions by allowing their flesh to beaten to a bloody pulp, it somehow seems perfectly fitting).

Bullet Ballet has a unique premise – a man becomes obsessed with trying to obtain a gun. What makes this an even more unusual premise is that this is a Japanese film and Japan is a country where private ownership of firearms is strictly forbidden. Bullet Ballet, for instance, could never have been made in the USA, where one can literally buy guns at your neighbourhood department store. In some ways, Bullet Ballet almost verges on being a science-fiction film in the sense that Shinya Tsukamoto is depicting a society where he has changed one element that is familiar (to us) and extrapolated a set of human reactions to it (even if what he is depicting is ultimately a society that exists in the real world). In these scenes, the film is filled with compulsively fascinating images – of Tsukamoto’s hero looking up gun catalogues on the internet, playing videoclips of guns being shot in slow motion, trying to buy a blackmarket weapon on the street (only in one amusing moment to end up being sold a children’s toy gun filled with sand), and then trying to manufacture his own gun (only to find that when he does fire it it has all the impact of a kid’s air pistol).

The photography, which Tsukamoto conducts himself, is shimmeringly beautiful – the entire film is shot in black-and-white. As though to echo the character’s obsessive state of mind, Tsukamoto shoots and edits with a dense, fractured look. The film is filled with frenetic strobe lighting, the camera hurrying through the glistering darkness of alleyways and basements, montages of taps and pipes dripping and drains flowing, while the daylight scenes are shot in a luminous grey that seems almost to let the screen fade into mist. One of the most beautiful scenes in the film is the one where Kirina Mano stands on the edge of subway platform, balancing on the very edge of the platform with her arms outstretched as a train comes past, buffeting in the slipstream and balancing only by the very tips of her boot heels.

On the minus side, it is not always clear what is happening in the plot. Tsukamoto never particularly concerns himself with sketching out what it is that connects his characters – we are not sure why Goda is attracted to Chisato, why he failed to pay her in the first place, who sent the message to him that announces that Chisato is going to die the next day, or why Chisato comes back and tells him that Goto has the gun. For that matter, we never even get to find out why his girlfriend killed herself and where she, considering all the problems that Goda experiences in trying to obtain a gun, managed to get hers from. And when he does obtain the gun, the character of the woman illegal immigrant who provides it just comes out of nowhere, saying she has been observing him and offering to marry him in return for providing the object of his desire, without any apparent motivation or foreshadowing – and with equal frustration drops out of the show and is forgotten immediately following the scene.

This almost total indifference to character motivation becomes more of a problem in the second half of the film where the obsessive thrust of the central character trying to find the gun that fuelled the first half drops away and we become wound up in the plot machinations of the relationship between Goda and Chisato and the various gang members trying to kill one another. Alas, in not knowing what is going on between the principals, these actions seem opaque to us. On the other hand, this doesn’t matter too much to the film. After all, Shinya Tsukamoto is not making a gangland film – any standard filmmaker might have opted for a more conventional plot, you could almost see a conventional version of the film turning out as something along the lines of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Outsiders (1983) – but rather a film about obsession. It is not the external plot machinations that drive the film, but the character’s inner need to fulfil his obsession – and at such, Bullet Ballet is completely successful.