Canada/UK. 1996.

Crew

Director/Screenplay/Producer – David Cronenberg, Based on the Novel by J.G. Ballard, Photography – Peter Suschitzky, Music – Howard Shore, Special Effects Supervisor – Michael Kavanagh, Production Design – Carol Spier. Production Company – Alliance Communications Corporation/RCP.

Cast

James Spader (James Ballard), Elias Koteas (Vaughan), Deborah Kara Unger (Catherine Ballard), Holly Hunter (Dr Helen Remington), Rosanna Arquette (Gabrielle)

Plot

Film producer James Ballard and his wife Catherine indulge in sex with others and gain pleasure by later recounting their escapades to one another. Ballard is then hit in a car crash. He survives but the driver of the other car is killed. As he makes a painful recovery, Ballard becomes erotically fascinated with car crashes. He meets and has sex with Helen Remington, the surviving passenger from the car he collided with. The two are drawn into the company of the charismatic Vaughan who leads a small group of fetishists that restage famous car crashes for their own arousal. Through this, both Ballard and Catherine are drawn to Vaughan and the fascinated possibilities he offers for erotic consumption in vehicular accidents.

J.G. Ballard (1930-2009) was one of the two or three key writers of the New Wave in literary science-fiction during the 1960s. The New Wave, which tended to centre around Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds magazine, was a loose movement, with many works often termed such in retrospect. Nevertheless, it brought an important change in that it sought to move away from outer space into inner spaces. New Wave science-fiction dealt less with the hardware of science-fiction – spaceships, aliens, robots, other worlds etc – than it did with social, psychological and political extrapolations, about the human reactions to outward futurism.

J.G. Ballard began publishing short stories in the 1950s. His first published novels were variants on the English disaster tradition as popularised by writers like H.G. Wells and John Wyndham, with works such as The Wind from Nowhere (1962), The Drowned World (1962), The Burning World/The Drought (1964) and The Crystal World (1966). Ballard was fascinated with the apocalyptic but in Ballard’s works you felt less the sense of humanity combating massive disasters than you do an author who loves the beauty of decayed, alienated landscapes and of characters who gain a cathartic psychological transformation as a result of the apocalypse.

J.G. Ballard’s work of the 1970s – his thematic trilogy consisting of Crash (1973), Concrete Island (1974) and High-Rise (1975) – were disaster stories of sorts in which desolate worlds now became contemporary urban landscapes where protagonists find their release by travelling beyond social taboo lines. Ballard’s best work may well be at short story length in collections such as The Terminal Beach (1964), The Disaster Area (1967), The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), Vermilion Sands (1971), Low Flying Aircraft (1976), Myths of the Near Future (1982) and Memories of the Space Age (1988).

Ballard is often criticised for lack of narrative and of being distant from his characters and it is at short story length that we see the true beauty of a J.G. Ballard work, where Ballard is more like a surrealist artist, crafting images of alien terrain and states of mind with words instead of pictures. The 1970s and up until his death in 2009 have shown Ballard’s move away from any easy allegiance to traditional science-fictional themes with works like The Unlimited Dream Company (1979), The Day of Creation (1987), Cocaine Nights (1996), Super-Cannes (2000), Millennium People (2003) and Kingdom Come (2006), a period that has also seen his acceptance by the mainstream literary establishment, with his books having been shortlisted for the prestigious Booker and Whitbread Prizes.

J.G. Ballard was born in Shanghai in 1930, where his father was the wealthy manager of a British textile manufacturing plant. Ballard spent his teenage years in an internment camp in Lunghua, Japan, as a prisoner of war after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. Ballard fictionally recounted his experiences there in his book Empire of the Sun (1984), which was filmed by Steven Spielberg as Empire of the Sun (1987). Both the book (and the Spielberg film in a more watered down way) show the key influences of Ballard’s childhood on his fiction – the fascination with desolate and destroyed landscapes, of humanity stripped away from its social confines and regressing to barbarism, and of people who rediscover themselves in the midst of disaster or who passively comply with the apocalypse.

J.G. Ballard’s fiction – particularly his work during the 1970s – has had a transgressive, taboo defiance that has courted considerable outrage – the US edition of The Atrocity Exhibition was pulped by its publisher over a story called Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan (which predicted that Reagan would become President). No work of J.G. Ballard’s has courted more controversy than Crash (1973). Ballard’s inspiration for Crash came from a mock art exhibition he staged in London in 1970 where he placed three wrecked cars on ‘display’ in a gallery. Said Ballard: “The behaviour of people who visited the gallery absolutely convinced me that I was onto something. At the opening people got so drunk. And over the course of the month they were on display the cars were attacked, one of them was overturned. Nobody would have noticed these cars in the street outside, but because they were isolated beneath the white gallery lighting they triggered enormous, confused emotions. So I thought, this is the green light. And so I sat down and began to write Crash.” Even when the novel was published, it attracted controversy with one publisher’s reader rejecting the manuscript with the much quoted comment “This author is beyond psychiatric help. Do not publish!”

There are many similarities between J.G. Ballard’s writing and the work of Canadian director David Cronenberg. David Cronenberg began making films in the 1970s. Like Ballard, Cronenberg started in genre material – B horror exploitation rather than science-fiction – with works like Shivers/They Came from Within/The Parasite Murders (1975), Rabid (1977), The Brood (1979), Scanners (1981), The Dead Zone (1983) and The Fly (1986). (Cronenberg’s only non-genre film within this time was appropriately enough Fast Company (1979), his least known work, about car racing). With films such as Videodrome (1983) and Dead Ringers (1988), Cronenberg began to define a startlingly original thematic terrain, moving away from traditional sf/horror themes into a distinctly Ballard-esque innerspace. Videodrome, Dead Ringers and to a lesser extent The Fly can be seen as films that occupy traditional sf/horror themes – mutation, mad science, mind control television – but instead take place inside their protagonists’ subjective space or where traditional horror movie themes have become more metaphorical horrors.

Into the 1990s, 2000s and beyond, Cronenberg has, just as J.G. Ballard did in the 1970s, moved away from easy genre pigeonholing and taken on works of controversy often dealing in sexually perverse material – his adaptation of William S. Burroughs (an author that Ballard has also cited as a major influence)’s Naked Lunch (1991), the non-genre M. Butterfly (1993), Crash, his adaptation of Patrick McGrath’s Spider (2002) that subjectively takes place inside a mentally ill man’s mind, A History of Violence (2005) about an assassin who has fled his violent past to reinvent himself as a family man, Eastern Promises (2007) about the Russian Mafia, A Dangerous Method (2011) about the early history of psychotherapy focusing on the relationship between Carl Jung and a sadomasochistic patient, Cosmopolis (2012), a surreal vision of contemporary economic collapse, and the dark Hollywood film Maps to the Stars (2014). All of these are works that take place inside interior landscapes of the mind and deal with often disturbing, genre-breaking taboo subjects.

The marriage between David Cronenberg and J.G. Ballard is certainly a most apt one. There are few other filmmakers who could lay claim to share a similar headspace to J.G. Ballard – maybe Peter Greenaway? It is for this reason that adaptations of Ballard have proven rare on cinema screens – there are not any easy footholds in Ballard’s works, he is not concerned with narrative and character. The most successful of J.G. Ballard’s adaptations, Steven Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun, is the least Ballard-like and most mainstream of his works. (The only other J.G. Ballard screen work up to this point has been Ballard’s purported but uncredited involvement in Hammer’s prehistoric drama When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970), which is almost the complete antithesis of Ballard’s work in its wilful embracing of schlock science-fiction elements.

Subsequent to Crash, we saw a number of other Ballard film adaptations, The Atrocity Exhibition (1998), the Portuguese Low Flying Aircraft (2002) and the British tv adaptation of Home (2003), albeit works with were not widely seen. Vincenzo Natali promised an adaptation of High-Rise for most of the 00s, which was then taken up by Ben Wheatley to emerge as High-Rise (2015), another fine and worthwhile Ballard adaptation. Crash is an uncommonly faithful translation of the book – J.G. Ballard poured accolades upon the film, saying it took the idea even further than he did, which surely must be a first for any screen adaptation of a book.

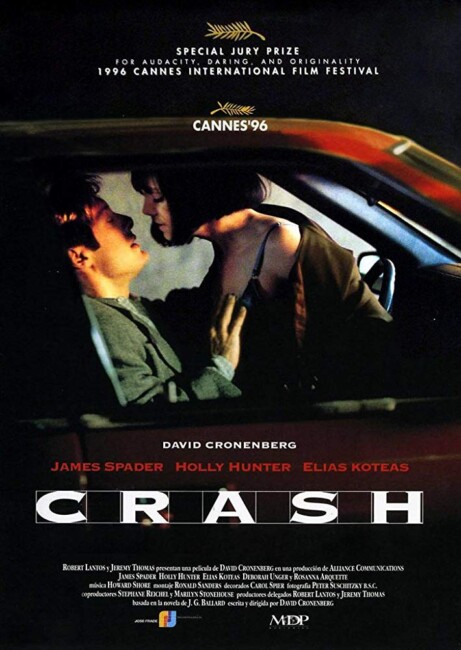

Crash the film was greeted with a storm of controversy when it opened. First there was the controversial Special Jury Prize awarded at the 1996 Cannes festival, something that was heavily debated by its own jury. Next, four local English councils, in an unprecedented move, passed a motion to ban Crash from being screened in the Greater London area. In the US, Ted Turner, the new owner of its distributor Fine Line Pictures, spoke out and refused to circulate the film. David Cronenberg fielded the storm of controversy with characteristic level-headeness. “There are two versions of Crash,” he said at the time, “one that exists on screen and one that exists in people’s heads.”

Certainly, Crash seems a peculiar film to field such controversy. It is neither pornographic, nor is it particularly violent. There is frequent sex in the film but more often than not it is portrayed in a detached rather than an erotic way – certainly, rarely with the steamy eroticism of a 9½ Weeks (1986) or a Basic Instinct (1992). Crash is certainly a disturbing film for its deliberate symbolic linking of sex and vehicular mayhem and its portrayal of people seemingly hellbent on consumption in car crashes. However, what one gains from the film is a striking examination of a peculiarly fetishistic mindset that may not even exist, rather than any erotic frisson.

You might compare Crash to other films like Gone in 60 Seconds (2000), The Fast and the Furious (2001) and sequels, or Torque (2004). These are films that also make implicit a connection between fast cars, car crashes and sex. The difference of course is that The Fast and the Furious is a work where the car is given an overt eroticism, where the destruction of vehicles is shown in loving slow-motion detail, and the audience is made implicit as part of the male fantasy of virility and power that the idea of fast cars embody; Crash is a film that, even though it predates these others, could be seen to lift the lids off the male fantasy and treat the implicit underlying connections with a wilful absurdity. In this sense, it is The Fast and the Furious that is the more disturbing film – Crash is certainly not a film that ever leaves one with a desire to get behind the wheel of a car and impel it into another as an erotic thrill; on the other hand, The Fast and the Furious does and it is entirely believable to think that it might inspire people to go out and does crazy things in cars. There is surely some hypocrisy of attitudes in the moral attack on Crash for its honesty in this sense, while films such as The Fast and the Furious pass without a second thought because they are pitched as mass entertainment.

One theme that runs through David Cronenberg’s work is the relationship between science and the individual. In the same way that J.G. Ballard in the 1960s took the disaster novel and transferred it from a dramatic story into a psychological process, so too in the 1970s David Cronenberg took the classic mad scientist film and transformed it into a psychological process – in Cronenberg’s films, the individual greets the process that will change them into something that exists somewhere between flesh and technology, between human and alien.

In Crash, that process is a peculiar new combination of sex and technology – the protagonists of the film repeatedly see a fatal melding with their machines as some type of erotic release. Coming upon a car crash on the highway in the film, Elias Koteas eagerly starts photographing it, posing Deborah Unger amidst the wrecked cars like she were a fashion model; people masturbate one another to video footage of car crashes as though they were pornographic videos, rewinding and freeze-framing over details of a crash as though it were a favourite scene. At the end of the film, James Spader runs Deborah Kara Unger off the highway in her car and then has sex in its wreck on the side of the road, commenting “Maybe next time” with a touch of sadness as though they have lost the chance for consumption this time. In one of the film’s most outré images, James Spader uses a scar on Rosanna Arquette’s leg as a substitute vagina. Famous car accidents are regarded with an erotic hagiography. (Crash would surely have had even greater controversy if Cronenberg had made it a year later than he did and it had come out subsequent to Princess Diana’s death in a car crash in 1997 – the sense of almost saintly mourning that followed almost touches with uncanny coincidence upon the absurdist fetishism that David Cronenberg projects here).

Most fascinating are the scenes where Cronenberg directly juxtaposes the imagery of erotica and machinery. In one scene following James Spader’s accident, Spader and Deborah Kara Unger masturbate one another while she describes the details of the wrecked cars in lingeringly fascinated adjective-filled detail as though it were the details of a sex act for them both to get off on. In another scene (perhaps the most genuinely erotic scene in the film), she asks him to describe the details, the colour and the smell of Elias Koteas’s car and, as he does, the descriptions slowly blend into the sexual as she asks him to imagine having sex with Koteas.

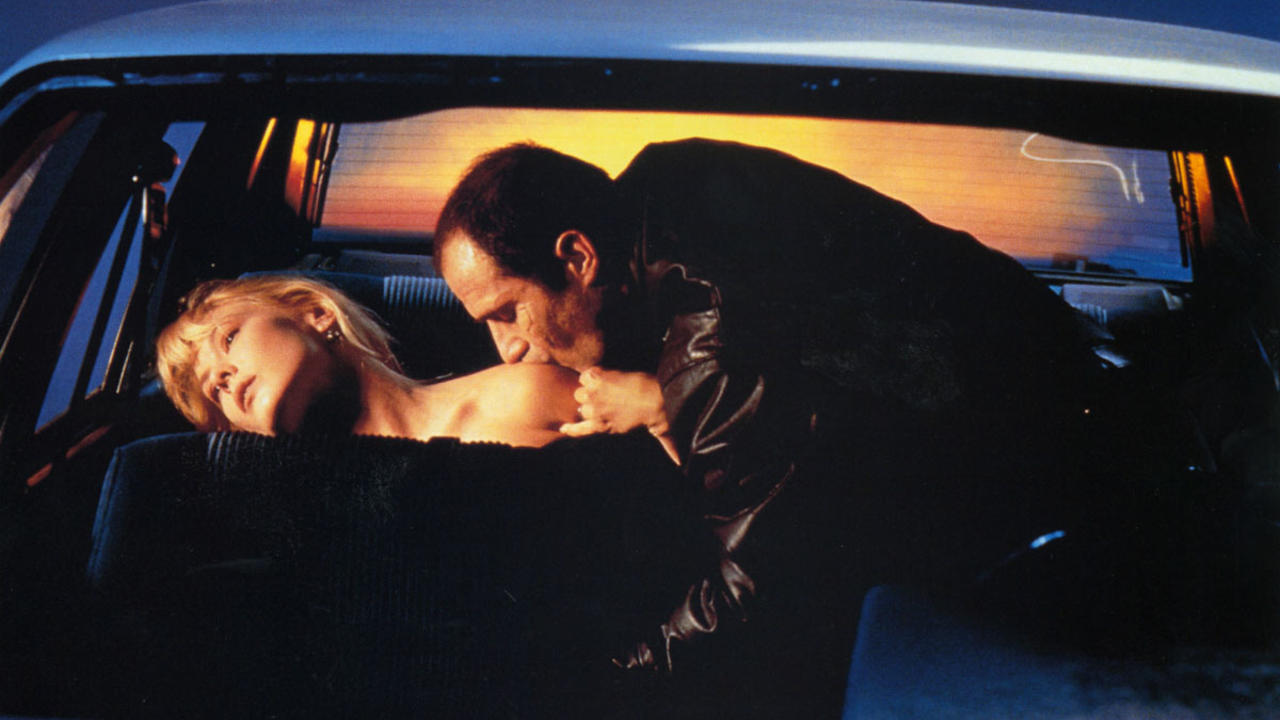

Equally, in the scenes where Cronenberg does portray sex, he deliberately depersonalises it – in the opening scene where Deborah Kara Unger is taken up against a plane in the hangar, she is almost entirely disconnected, seen being undressed, her breasts and tongue caressing the metal of the wing but rarely her face. During the sexual interludes, Cronenberg focuses more on the machinery around the people than he does the thrusting bodies – in the scene where Deborah Kara Unger and Elias Koteas have sex in the back of a car, Cronenberg focuses more on the machinery of the carwash shifting around them than he does the bodies; as James Spader has sex with Unger on the balcony near the beginning, Cronenberg’s camera moves away from them to focus on the busy highway below; and while Elias Koteas makes out with a hooker in the back of his car, Cronenberg focuses on James Spader caressing the steering wheel as he drives. It is a fascinating juxtaposition.

Cronenberg even goes so far as to characterise the characters in the film by the cars they drive – James Spader’s anonymous Japanese import seems to betoken the soulless character he is; Deborah Kara Unger’s silver sports car projects the same sharp sophistication that she does; while Vaughan drives a beaten-up black machine that radiates the same dangerous macho quality that Elias Koteas projects on screen.

Crash also allows David Cronenberg’s rare sense of deadpan black humour to come to the fore – like in the scenes with Elias Koteas eagerly planning to restage the Jayne Mansfield decapitation as stuntman Peter MacNeill lies badly injured. Upon seeing a dent in the side of her car, James Spader makes the comment to Deborah Kara Unger that it “must be a suitor”, as though in this perverse world crashing into someone’s car has the same equivalence as delivering roses. Frequent Cronenberg collaborator Howard Shore contributes a cool, alienating score.

The film’s depersonalised style is well suited to James Spader’s detached acting style. Deborah Kara Unger gives a fine performance – the scene with her getting turned on as James Spader talks about Elias Koteas is remarkable. However, it is Elias Koteas, in a performance of intensive macho extroversion, who succeeds in stealing the entire show.

David Cronenberg’s other films are:– Stereo (1969), a little-seen film about psychic powers experiments; Crimes of the Future (1970) set a future where people have become sterile and developed strange mutations; Shivers/They Came from Within/The Parasite Murders (1975); Rabid (1977) about a vampiric skin graft; The Brood (1979) about experimental psycho-therapies; Fast Company (1979), a non-genre film about car racing; Scanners (1981), a film about psychic powers; Videodrome (1983) about reality-manipulating tv; The Dead Zone (1983), his adaptation of the Stephen King novel about precognition; The Fly (1986), his remake of the 1950s film; Dead Ringers (1988), his greatest film, about two disturbed twin gynaecologists; Naked Lunch (1991), his surreal adaptation of William S. Burroughs’ drug-hazed counter-culture novel; M. Butterfly (1993), a non-genre film about a Chinese spy who posed as a woman to seduce a British diplomat; eXistenZ (1999), a disappointing film about Virtual Reality; Spider (2002), a subjective film that takes place inside the mind of a mentally ill man; the thriller A History of Violence (2005) about a hitman who has taken up a new identity; Eastern Promises (2007) about the Russian Mafia; A Dangerous Method (2011) about the early years of psychotherapy; Cosmopolis (2012), a surreal vision of near-future economic collapse; the dark Hollywood film Maps to the Stars (2014); Crimes of the Future (2022) set in a future world of surgical performance art; and The Shrouds (2024) about the development of a technology that places videocameras inside graves. Cronenberg has also made acting appearances in other people films including as a serial killer psychologist in Clive Barker’s Nightbreed (1990); a Mafia hitman in To Die For (1995); a Mafia head in Blood & Donuts (1995); a member of a hospital board of governors in the medical thriller Extreme Measures (1996); as a gas company exec in Don McKellar’s excellent end of the world drama Last Night (1998); as a priest in the serial killer thriller Resurrection (1999); and a victim in the Friday the 13th film Jason X (2001).

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 1996 list. Nominee for Best Director (David Cronenberg), Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actress (Deborah Kara Unger), Best Supporting Actor (Elias Koteas) and Best Musical Score at this site’s Best of 1996 Awards).

Trailer here