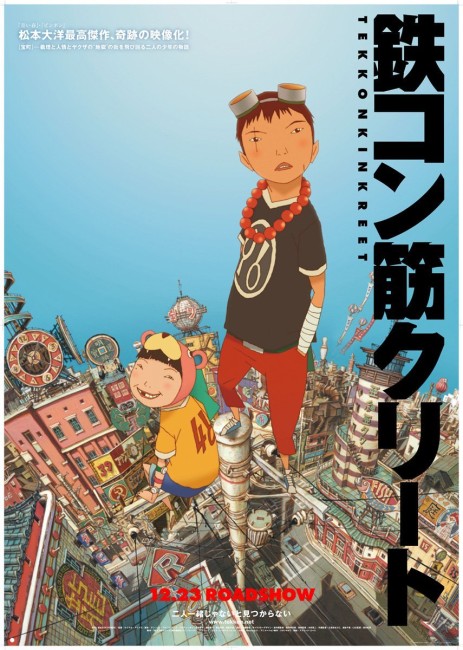

aka Tekkon Kinkreet

Japan. 2006.

Crew

Director – Michael Arias, Screenplay – Anthony Weintraub, Based on the Manga Tekkonkinkreet (1993-4) by Taiyo Matsumoto, Producers – Eiichi Kamagata, Eiko Tanaka & Fumio Ueda, Animation Supervisor – Shoujiro Nishimi, Music – Plaid, Art Direction – Shinji Kimura. Production Company – Asmik Ace/Aniplex/Studio 4oC.

Plot

In the rundown inner city area known as Treasure Town, two young homeless children nicknamed The Cats, who call themselves Agent Black and Agent White, run free through the streets, surviving by stealing money and living in an old abandoned car. The older Black regards the inner city as ‘his town’. They then witness yakuza led by Fujimura arriving in town and muscling out the friendly Apache gang that run the neighbourhood. When Black attacks and humiliates the yakuza, Fujimura allows the sinister man known as Snake to come in and take over. Snake plans to raze Treasure Town to build an amusement park. He employs assassins with strange powers to hunt down The Cats but Black and White prove more difficult to catch than anticipated. When White is injured, Black leaves him in the care of the police and goes out on his own where his anger becomes increasingly darker.

Tekkonkinkreet is an anime from Studio 4oC, the group who has worked as an animation studio for hire on anime like Spriggan (1998), Metropolis (2001) and Steamboy (2004) and eventually became an independent studio with episodes of Western-backed anthologies like The Animatrix (2003), Batman: Gotham Knight (2008), Halo Legends (2010) and Green Lantern: Emerald Knights (2011), and in Japan made the feature Mindgame (2004), the anthology Genius Party Beyond (2008), First Squad: The Moment of Truth (2009) and Street Fighter IV: The Ties That Bind (2009).

The fascinating thing about Tekkonkinkreet is that it is the first anime to be made by a gaijin director – in this case, American Michael Arias. Arias is married to a Japanese woman and has lived in Japan for sixteen years. Arias was a former computer graphics designer who had developed software for various computer games and CGI animated films, including a program that allows CGI animation to develop shadings. Arias had worked in various (usually uncredited) capacities on films like The Abyss (1989), Fat Man and Little Boy (1989) and The Hudsucker Proxy (1994) and his first major film credit was as a sequence producer on The Animatrix. He developed Tekkonkinkreet as long ago as 1999, originally starting it as a short computer-animated film along with Studio 4oC co-founder Koji Morimoto.

Michael Arias directs some exhilarating animated action sequences. The film opens on a marvellous sequence with the two kids racing around the streets and avoiding pursuers by leaping from building to building and objects in the street, before a confrontation atop a clock tower where the rival is disposed of by the emergence of a giant statue of the elephant god Ganesha on the hour. There is another fine sequence during the middle of the film with the two kids being pursued by the assassins around the street, over vehicles and along a train roof. Arias impresses considerably with his ability to direct action in a way that has a three-dimensional kineticism more like a live-action action film.

Perhaps the single most striking aspect about Tekkonkinkreet is the backgrounds. In fact, without these, Tekkonkinkreet would be considerably less than it is. Michael Arias creates extraordinary panoramas that leap out at you like three-dimensional canvases, filled with dense and exactingly detailed background minutiae of buildings and street life. There is something here that strongly resembles the artwork in Hergé’s Tintin comic-books, where Hergé used to obtain photographs of existing real world locations and draw densely detailed artistic replications of these.

The world of this fictional inner city that the drama takes place against is constantly present element to the extent that it is almost like a major character in the film. The overriding theme of Tekkonkinkreet is one of nostalgia in the face of gentrification – a sadness at seeing a rundown inner city urban landscape and the colourful life that inhabits it being bulldozed by progress.

The script creates a host of finely nuanced characters that have often surprising depths to them. The relationship between the two kids is often bittersweet and touching. It is a moody inner story that in a latter half becomes something that could almost be construed as a lone vigilante drama a la Batman Begins (2005) without ever emerging out and adopting the tropes of the superhero genre. The plot is written on a large canvas and doesn’t always come together – but then Michael Arias and his writer Anthony Weintraub are adapting a manga, Black and White/Tekkon Kinkreet published between 1993-4 in Weekly Big Comic Spirits, that was originally 600 pages long.

Perhaps the major problem that I had with Tekkonkinkreet is the very reason for its inclusion here as a fantasy film. The fantastic elements seem awkwardly integrated into the story. The two kids, Black and White, have the possibly fantastical ability to make superhuman leaps between buildings and fall from great heights without injury. Later in the piece, the villain Shark employs a trio of assassins who also seem to have never-explained superpowers in terms of great strength and in particular the ability to fly across the city. None of these abilities are ever commented on, they just are.

Various other commentators have called the two kids superheroes, seen the assassins as aliens or androids, as well as seen the city landscape as futuristic or an alternate world, but in terms of genre definitions, it feels difficult to make a case for any of these being the case. It would be equally possible to make an entirely mundane case for Tekkonkinkreet taking place in a fictional present-day city. There is also a beautifully animated sequence near the climax that heads into impressionistic oil colour animation as Black fights against a demonic alter ego of himself, although this is clearly an allegorical inner battle of the soul that is going on, not any outward manifestation.

Director Michael Arias subsequently went onto make the live-action Japanese film Heaven’s Door (2009), a non-genre film about the relationship between an older man a girl who both have terminal illnesses, and then returned to animation with the science-fiction film Harmony (2015).

Trailer here