(Inosensu: Kôkaku Kidôtai)

Japan. 2004.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Mamoru Oshii, Based on the Manga by Shirow Masamune, Producers – Mitsuhisa Ishikawa & Toshio Suzuki, Photography – Miki Samura, Music – Kenji Kawai, Animation Supervisors – Naoko Kusumi & Toshihiko Nishikubo, Visual Effects Supervisor – Hisashi Ezura, Digital Effects Supervisor – Hiroyuki Hayashi, Production Design – Yohei Taneda. Production Company – Production I.G./Studio Ghibli/Tokuma Shoten/Bandai Visual/Dentsu/Kodansha IG-Ltd.

Plot

Batou, the cyborg operative from Section 9, has been paired with a new partner Togusa but still misses his old colleague Major Kusanagi. The Section chief assigns them to investigate a series of incidents where the gynoid androids produced by the Locus Solus corporation have gone amok and killed humans and to find out why these incidents are not being reported to the police. Batou and Togusa discover that the reason for this is because the gynoids have been created as sex androids. Their investigation takes them to the mysterious lawless region where the Locus Solus conglomerate operates from and the company’s CEO exists as a soul that has been downloaded into a lifelike doll’s body.

Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence is a sequel to Ghost in the Shell (1995), an anime venture into the Cyberpunk genre that became a cult hit in the West. Behind both films is Mamoru Oshii, who is rapidly becoming one of the most fascinating directors in anime. Oshii worked as a director in various anime tv series before moving into feature film work with the children’s fantasies Urusei Yatsura: Only You (1983) and Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer (1983), both adapted from a tv series he had worked on, the science-fiction film Dallos (1983), the surreal fantasy film Angel’s Egg (1985) and the Transformer robot films Patlabor: The Mobile Police (1989) and Patlabor: The Movie 2/Patlabor: The Mobile Police 2 (1993). In between this, he moved into live-action with the SF action Red Spectacles (1987) and its follow-up Stray Dogs (1991), and the non-genre Talking Head (1992).

Oshii followed Ghost in the Shell with another science-fiction film, the stunningly stylised live-action shot Avalon (2001) and subsequently went onto the anime The Sky Crawlers (2008), the live-action Assault Girls (2009) about virtual videogamers, an episode of the anime anthology Halo Legends (2010) and the live-action clone wars film Garm Wars: The Last Druid (2014). Oshii has also written the anime Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade (1998) about a werewolf anti-terrorist squad operating in an alternate world post-War Japan, and produced the impressive anime short Blood: The Last Vampire (2000) about a vampire government agent engaged in a war with demons.

What makes Mamoru Oshii such an absorbing director is his increasing desire to push an artistic envelope. Avalon was an utterly fascinating attempt to blur the line between anime and live-action, resulting in a film that looked unlike anything seen on screen before; while both Ghost in the Shell and Jin-Roh grapple with highly conceptually challenging ideas. Oshii makes his first venture into CG animation with Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence and it emerges as his best film to date.

Oshii pushes the boundaries of both CG and Cyberpunk artistically. This is immediately apparent from the stunning opening shot across a city, which is lit up in lights like a flaming inferno as we follow a heavily armed helicopter that on closer glance proves to be a transformer on patrol. The usual line-up of weapons and mechanical designers that appear on the credits in anime have a field day coming up with dazzling touches of Cyberpunk technology to fill the background of the film.

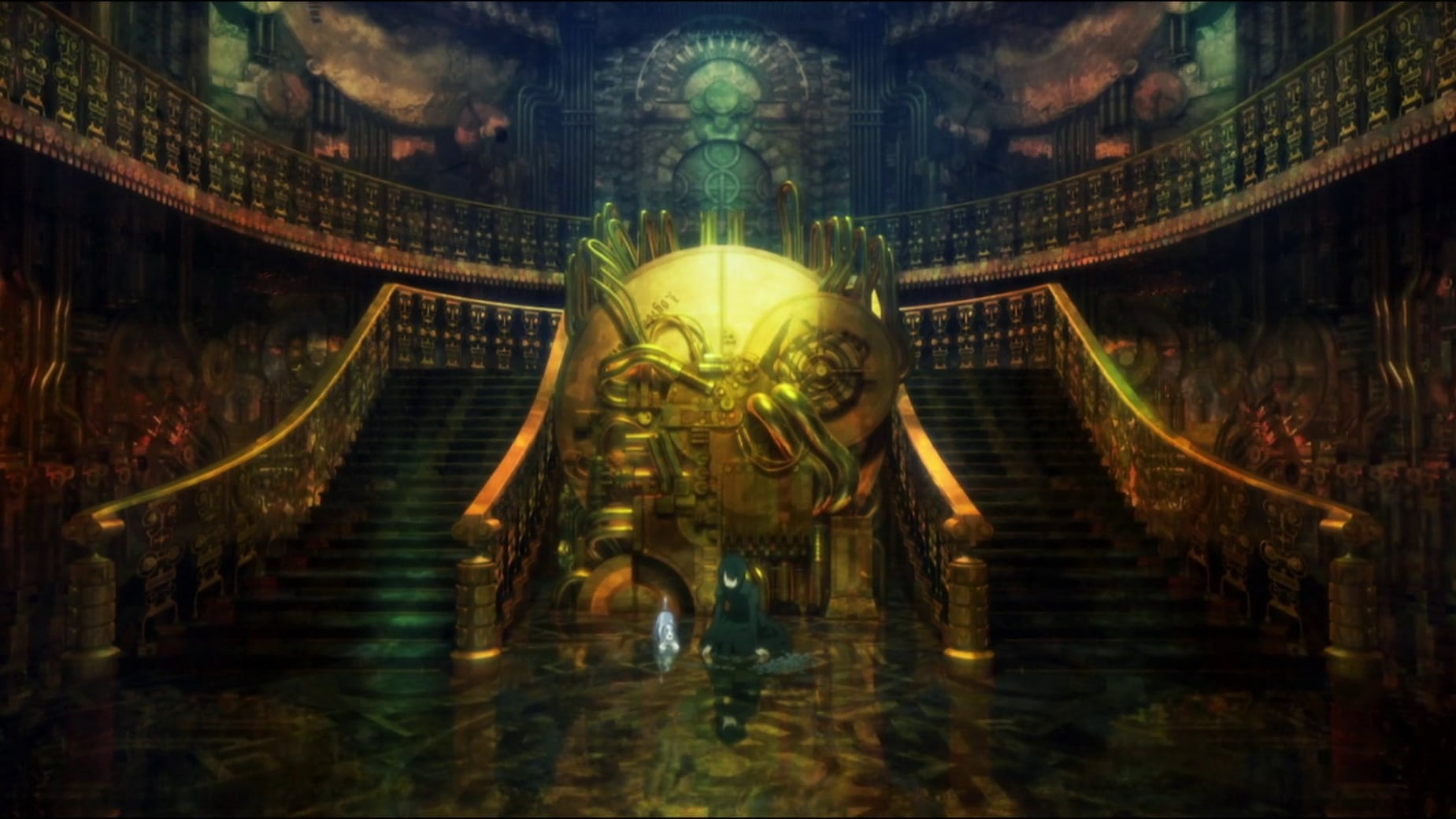

The most stunning moments in Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence come during the venture into the lawless region of the Locus Solus headquarters, where Mamoru Oshii and his animators create some extraordinary visions:– a cathedral lit up in light, traditional Chinese temples, giant samurai robots marching in a street parade, an English mansion incongruously sitting in the middle of an artificial lake, friezes of giant birds caught against skylights, corridors of stained glass, cryptic cabalistic symbols, the rusting statues of giant robots. The artistry in these scenes is astonishing. Indeed, in Mamoru Oshii’s love of abstract landscapes, Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence is perhaps the closest that any film has yet come to depicting the essence of J.G. Ballard’s science-fiction.

In Mamoru Oshii’s films there lies a fascination with philosophical questions – the characters who question what part of themselves is real and what cyborg in Ghost in the Shell; the striking twist unveiling of Avalon; the clones coming to a slow awareness of their purpose in The Sky Crawlers; and Jin-Roh with its fascinating play of metaphors between Little Red Riding Hood, werewolves and terrorism. Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence comes with a series of beautifully melancholic reflections on the nature of humanity and its simulacra. The roboticist Haraway has a haunting speech where she asks what the difference between robots and children is, and there is a later voicover from the character of Kim about how a doll should not be considered as non-human but a reflection of humanity. Oshii even crafts a softly touching relationship between the cyborg Batou and his basset hound.

It is also Mamoru Oshii’s failing that he frequently intellectually overreaches in his ideas. Jin-Roh came fired up with a superb metaphor that failed to make itself adequately understood. Oshii seemss to be trying a little too hard to show his intellectual credentials here – having characters talk in haiku frequently throughout and dropping references and quotes to everything from Milton and The Bible to the legend of the Golem and even Villiers de l’Isle Adams (the 19th Century French writer who wrote one of the first works to feature an android).

Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence certainly becomes confusing trying to follow its plot, especially during the middle when characters become caught up in a virtual reality loop that keeps repeating itself, even if everything does eventually become clear. It is clear that for Mamoru Oshii narrative is a concern that ranks second behind the sheer artistry of the film and his philosophical ruminations – that said Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence is a film of extraordinary beauty and hauntingly meditative reflection on the nature of humanity and the artificial.

The Ghost in the Shell series was subsequently revived in a series of four one-hour theatrical films under the title Ghost in the Shell: Arise (2013-4) and a further animated film Ghost in the Shell: The New Movie (2015), followed by a further anime tv series Ghost in the Shell SAC_2045 (2020-2). Ghost in the Shell (2017) was a live-action English-language remake starring Scarlett Johansson.

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 2004 list).

Trailer here