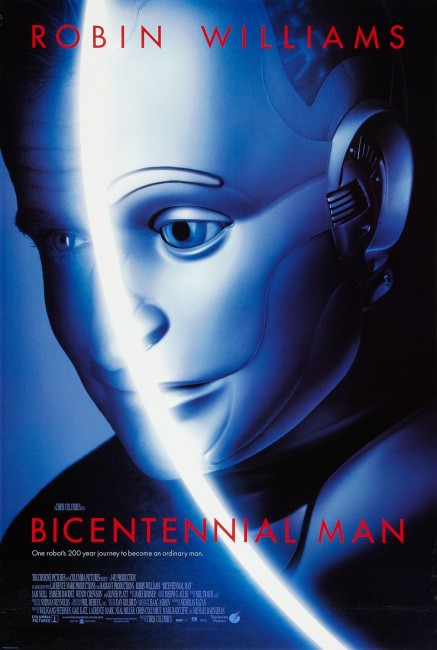

USA. 1999.

Crew

Director – Chris Columbus, Screenplay – Nicholas Kazan, Based on the Short Story by Isaac Asimov and the Novel The Positronic Man by Isaac Asimov & Robert Silverberg, Producers – Chris Columbus, Michael Barnathan, Gail Katz, Laurence Mark, Neal Miller, Wolfgang Petersen & Mark Radcliffe, Photography – Phil Meheux, Music – James Horner, Visual Effects – DreamQuest Images (Supervisor – Dan Deleeuw), Visual Effects Supervisor – James E. Price, Special Effects Supervisor – John McLeod, Robotic Effects – Steve Johnson’s XFX Inc, Old Age Makeup – Greg Cannom & Keith Vanderlaan’s Captive Audience Productions Inc (Supervisor – Brian Sipe), Production Design – Norman Reynolds. Production Company – Touchstone/Columbia/1492/Laurence Mark Productions/Radiant Pictures.

Cast

Robin Williams (Andrew Martin), Embeth Davidtz (Little Miss Martin/Portia Martin), Sam Neill (Richard Martin), Oliver Platt (Rupert Burns), Wendy Crewson (Mrs Martin), Stephen Root (Dennis Mansky), Kiersten Warren (Galatea), Hallie Kate Eisenberg (Young Little Miss)

Plot

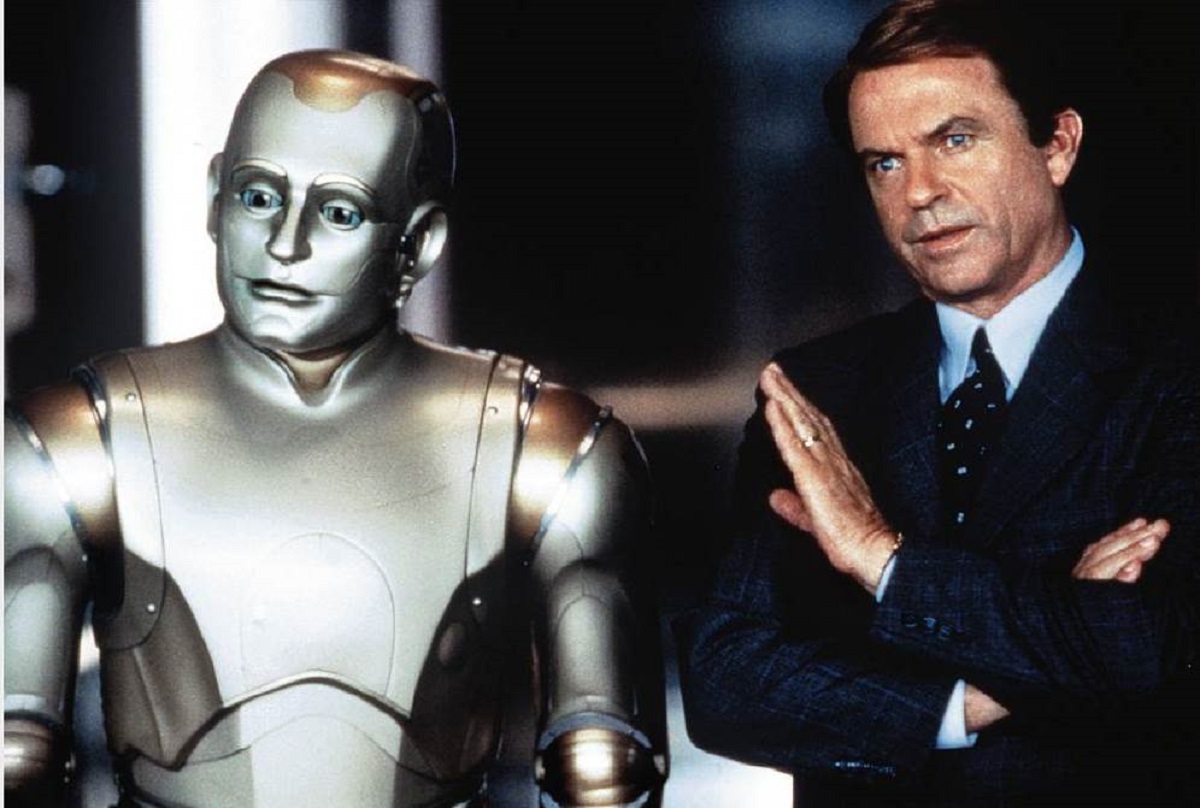

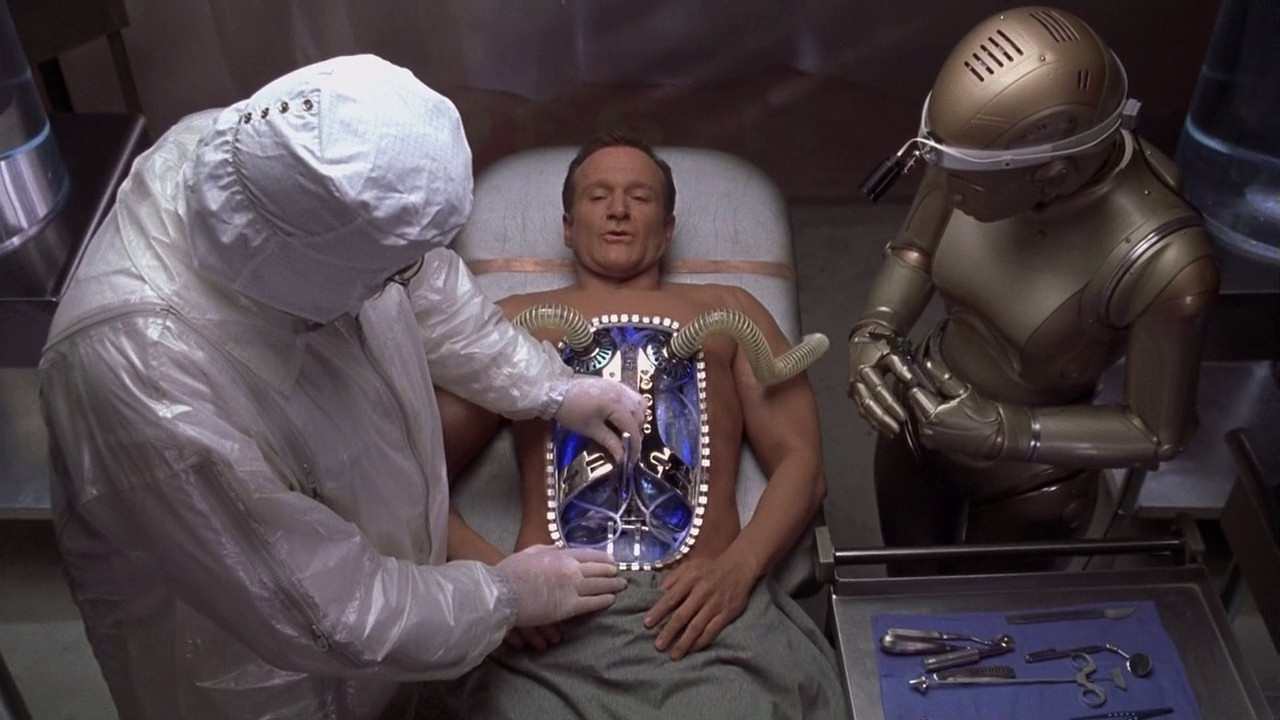

Richard Martin buys a new android for work around the house and the family name it Andrew. As Andrew becomes an accepted part of the family, they find it developing human characteristics – artistic instinct, the ability to tell jokes – something the manufacturer puts down to being a programming malfunction. As Richard grows old and dies and his daughters grow into old women, Andrew substitutes new parts until he develops an increasingly more human-like appearance and eventually a nervous system. Throughout the years, Andrew’s strongest desire is to obtain freedom and find others of his kind. Eventually he tries to find legal acceptance as a human being so that he can marry Richard’s granddaughter.

Isaac Asimov (1926-92) may not have been the world’s greatest science-fiction writer, even if he is often seen as such by people outside the science-fiction field. Asimov’s characterisation, when not underwrit by a schoolboyish sexism, was non-existent to wooden and his plotting stilted. What Asimov did well – and it is an object lesson as to why science-fiction triumphs as a literature of poetry and concepts over the pulp prose and B-grade cinema it is frequently embedded in – was toy with grandiose ideas, be it the logical loopholes that can ensue in attempting to define behavioural rules for robots, the idea of a civilisation seeing night for the first time or the cosmological grandeur of a sociologist trying to prevent the fall of an entire galactic empire.

When Asimov was good – the first four Foundation books, the I, Robot stories, The Gods Themselves (1972) – he was good – but he could also be terrible – the Foundation prequels, Nemesis (1989) and the overinflated attempts to unify all his stories into one universe that he conducted in the last decade of his life. Rather than his science-fiction, Isaac Asimov’s best work is probably still the enormous body of non-fiction books he wrote wherein he brought his prodigious and much vaunted intellect to bear on popularising various aspects of science and history.

However, there was one thing that Asimov amid his many faults was not and that was a shabby sentimentalist. Bicentennial Man, which is ‘loosely’ adapted from Asimov’s Hugo-winning 1976 short story and the novel length expansion he co-wrote with Robert Silverberg in 1993, is appalling sentimental tripe. Asimov, even when writing at his worst, would never have churned out something as agonisingly maudlin as this. An Asimov story would always trace a path of logic – when a robot became sentient, you would at least get Asimov engaging in a debate about what humanity meant or about what caused spontaneous development of artificial intelligence.

Bicentennial Man the film, on the other hand, trades in a preposterous humanocentric romanticism. It swims in the same hearts and flowers sentiments that fill inspirational greeting cards. The scenes where Andrew’s various human companions die simper in an appalling mawkishness and the stabs at romance are so corny that they verge on the laughable.

The film was directed by Chris Columbus, who previously made soggy-headed light comedies such as the Home Alone (1990), Mrs Doubtfire (1993), 9 Months (1995) and would go onto make Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone/Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001) and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002). As might be expected, Chris Columbus’s hand with comedy and emotion flies with all the sparkle and elegance of a lead brick.

The scenes at the end with the robot arguing for the right to be legally regarded as human and to grow old and die are scenes that you could have imagined Asimov having made work through the logical sophistry that his robot stories worked on, but under Chris Columbus’s hand, they come out with such a puerile soft-headedness that they dissolve into laughability. Instead of Asimovian insight, all that Bicentennial Man has is the maudlin assumption that it is good to be human – and yet in the end, all it does is get sentimental about it and fails to offer a single argument as to why a robot might think so.

This is a science-fiction film for people who don’t like science-fiction. Bicentennial Man is to Isaac Asimov and any debate about AI what Forrest Gump (1994) was to Platoon (1986), what Jakob the Liar (1998) is to Schindler’s List (1993) – it is a science-fiction film for people who prefer feelgood greeting card sentimentalism over a film that actually has a single thing to say about anything.

Despite their popularity, Isaac Asimov’s works had fared unevenly in the media. Several of his stories were adapted for the British science-fiction anthology tv series Out of the Unknown (1965-71); Asimov was hired by Harvey Weinstein to write the English-language script for the American release of the French animated film Gandahar/Light Years (1988); he came up with the premise of the excellent but short-lived tv series Probe (1988); his classic short story Nightfall (1941) was made it into two obscure B-budget films, Nightfall (1988) and Nightfall (2000); and he gave loose inspiration to the tv movie The Android Affair (1996). The only other full-fledged Asimov screen works have been I, Robot (2004), which disappointingly only grafted the name of Asimov’s story collection onto a standard robots amok screenplay, and the tv series Foundation (2021- ). The only other Robert Silverberg works to be adapted to the screen have been the films Amanda and the Alien (1995) and Needle in a Timestack (2021).

Chris Columbus started his career writing screenplays for various Steven Spielberg productions – Gremlins (1984), The Goonies (1985) and Young Sherlock Holmes (1985), before making his directorial debut with the teen comedy Adventures in Babysitting/A Night on the Town (1987). Columbus directed the first two Harry Potter films and acts as Executive Producer on the subsequent entry Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004). He followed this with Percy Jackson & The Olympians: The Lightning Thief (2010) about a teenager who discovers his heritage as a Greek demi-god and the comedy Pixels (2015) in which alien invaders recreate classic arcade videogames. Columbus also co-wrote the script for the animated Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989). In the mid-1990s, Columbus planned a film version of Marvel Comics’ Fantastic Four, although only acts as producer on the finished film version, Fantastic Four (2005) and its sequel Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007). Columbus is also Executive Producer on Monkeybone (2001), Night at the Museum (2006) and its sequels Night at the Museum 2 (2009) and Night at the Museum: Secret of the Tomb (2014), Percy Jackson: Sea of Monsters (2013), The Witch: A New-England Folktale (2015), I Kill Giants (2017), The Lighthouse (2019), Scoob! (2020), Chupa (2023) and Nosferatu (2024). He heads the 1492 Productions production company – the date being an obvious play on his more famous namesake.

Trailer here

Full film available online here:-