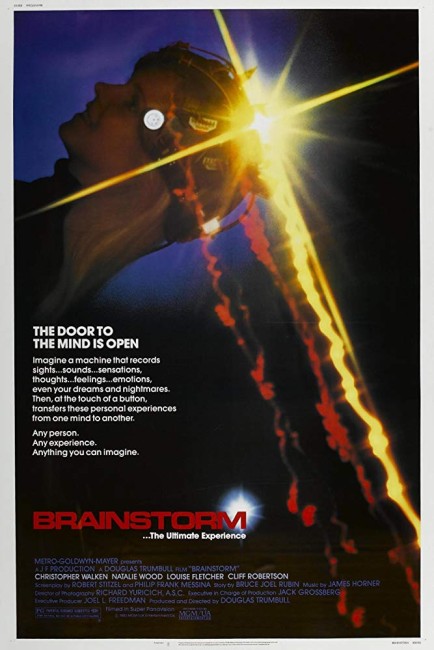

USA. 1983.

Crew

Director/Producer – Douglas Trumbull, Screenplay – Philip Messina & Robert Stitzel, Story – Bruce Joel Rubin, Photography – Richard Yuricich, Music – James Horner, Visual Effects Supervisors – Douglas Trumbull & Allison Yerxa, Computer Effects – Don Baker, Animation Supervisor – John C. Walsh, Makeup – William Munns, Production Design – John C. Vallone. Production Company – MGM-UA.

Cast

Christopher Walken (Michael Brace), Natalie Wood (Karen Brace), Louise Fletcher (Lillian Reynolds), Cliff Robertson (Alex Terson), Joe Dorsey (Hal Abramson)

Plot

Scientists Michael Brace and Lillian Reynolds build a device capable of recording and playing back sensory experience. As they experiment with its various possibilities, Lillian dies of a heart attack but manages to record the experience. Following her death, the project is taken over and shut down by their military backers and Brace forbidden to view the tape. With the help of his estranged wife Karen, Brace conducts a telephone hack-in to access the tape and view the recorded experience of the afterlife.

Douglas Trumbull is an interesting name within the science-fiction genre. Trumbull’s principal field of expertise is visual effects and he has conducted work on high-profile films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), The Andromeda Strain (1971), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Star Trek – The Motion Picture (1979) and Blade Runner (1982). For a time during the late 1970s, Trumbull was considered the top name in special effects. Indeed, Close Encounters drew Trumbull as much attention within the genre press at the time as it did Steven Spielberg. (Although since Brainstorm, Trumbull has dropped into almost total obscurity).

Trumbull is multi-disciplined, having also turned director with the interesting science-fiction film Silent Running (1972). Brainstorm was Douglas Trumbull’s second feature film as director and the last he has made to date. Trumbull chose this project to showcase his longtime interest in 70mm widescreen filmmaking. Brainstorm was shot in standard 35mm but the screen opens up to 70mm for the point-of-view scenes of the device in operation. During the film’s original theatrical release, the screen would change between the two formats, an effect that is totally lost on tv and video screenings these days.

Brainstorm has a dazzling central concept – even if most of the idea is stolen from D.G. Compton’s novel Synthajoy (1968). This makes Brainstorm one of the first films to deal with Virtual Reality – well before the term was actually coined. The other novelty that Brainstorm also holds is that it and WarGames (1983), which came out three months earlier the same year, were the first ever films to depict the internet in use.

It is also one of the few science-fiction films that create a credible picture of scientists at work in the laboratory – you keep feeling that were the device an actual one, you are right in the midst of its development. The idea of the film managing to record the experience of the afterlife is an intriguing one – although one has doubts that when you are having a heart-attack alone in a laboratory whether your first impulse would be to slip on a sensory recording device to record the experience rather than say picking up the phone and dialing 911.

The most interesting parts of the film are those that show the capabilities of the device – one man trapping himself in a continuous loop of sexual experience or where Christopher Walken’s son accidentally enters the experience of a psychotic. We are introduced to the device in a fascinating opening scene where we see Walken sitting with the headset on as someone else walks about recording their experiences – tasting odd mixtures of food, someone tapping their knee and Walken’s leg involuntarily jumping, and then a prankster swapping the data feed with one attached to a lab monkey’s brain.

Yet for all the fascinating aspects inherent in the idea, it is something that the film fails to fulfill in entirely satisfactorily ways. Beyond these scenes, the film comes across largely as an extended IMAX test reel. It suffers from the same problems that all IMAX featurettes do – that super-widescreen filmmaking, while excellent for highly intense depiction of the pictographic, tends to so overwhelm the senses that it makes it difficult for telling all but the simplest stories. There are lots of nice widescreen scenes hang-gliding and riding on rollercoasters but the film still looks like a widescreen travelogue.

Certainly, watching Brainstorm today does provide some unintentional amusement – like how the ultra-low bandwidth that would have been available back in 1983 would have been absurdly inadequate for transmitting a recorded sensory experience when two decades on standard usage was still struggling to cope with streaming video in any kind of worthwhile resolution. Not to mention the fact that Christopher Walken is conducting this entire hack-in via a public telephone box. It’s also amusing to see all of this being conducted in the era that was pre-Windows and the advent of the graphic user interface environment – meaning that when Christopher Walken opens a file he has to type in the full MS-DOS pathname rather than double-click on it with a mouse.

It is interesting also to contrast Brainstorm to WarGames – both feature plots about people hacking into military installations but approach the story from quite different angles. WarGames director John Badham is a technological alarmist who fears the problems of our technology going out of control – chaos is caused when an hacker breaks in innocently thinking he has found a new videogame; by contrast, Douglas Trumbull is a prophet of science and technology to whom the military are covering up the truth and it is his protagonist’s duty to defy the law and hack in to get the truth and to whom causing technological chaos in the furtherance of this goal is perfectly justifiable.

But when Brainstorm tries to develop a plot, it merely resorts to military paranoia cliches and a laboratory destruction sequence that seems clumsily inserted. Trumbull’s editing and set-ups are often sloppy – these scenes all but verge on slapstick. The sense of wonder of the climactic venture into the afterlife is considerably undone by Trumbull constantly cutting away to the scenes of Natalie Wood hacking into the computer.

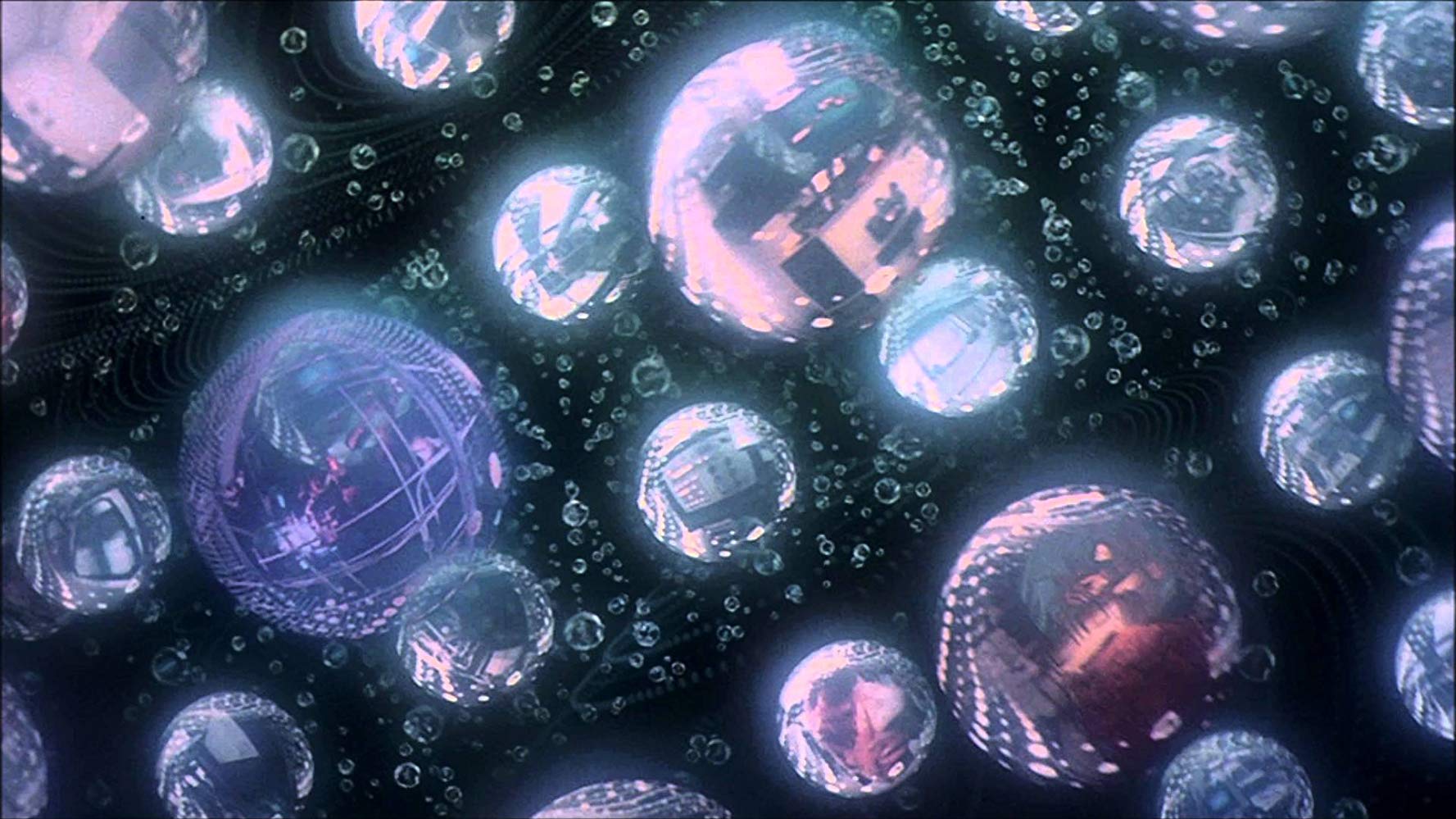

Trumbull is a far better effects man than director and certainly his view of the afterlife is stunning (even if the idea of Heaven looking like the inside of a computer circuit is one that goes strangely uncommented on). In these sequences, Trumbull returns to something of the pioneering Slit Scan lightshow he created for 2001 (the sequence where Keir Dullea travels through the stargate). For Stanley Kubrick, the stargate scenes were about an ordinary man taking a journey into a transcendental state of consciousness. On the other hand, Trumbull’s vision tends to be a sentimental one. He wants to see the merging of science and religion as a breakthrough in human consciousness – with heavy-handed symbolism, the climactic hack-in takes place right outside the monument to the Wright Brothers’ first flight at Kitty Hawk. Yet for all that, he seems to only rely on traditional religious imagery – angels in the afterlife, souls in communion. It was the problem that occurred after Close Encounters, which opened things up in terms of transcendental shifts of consciousness and meetings with the alien in a big way. A number of subsequent films opted less for evolving beyond what we know (as Stanley Kubrick did) than simply reaffirming the familiar. Like The Black Hole (1979), Brainstorm sees all that is out there is a very traditional view of Heaven (no mention of Hell); while, like Altered States (1980) and The Abyss (1989), it sees that the mysteries of the entire universe are best dealt with by the scientist returning to the comfort of his wife’s arms.

The hero of the show is played by Christopher Walken in one of his first major lead roles and is okay, although it is just Walken in a regular role, not the point he managed to let his penchant for eccentric and individual roles find their feet. Trumbull also casts Louise Fletcher, who became a name after her Academy Award winning success at Nurse Ratchet in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975). But almost immediately after that, Fletcher seemed to drop into supporting roles that required her to play a middle-aged frump (and these days a grandmother). She never again played anything that came anywhere near One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and the whole of her subsequent career is a long slide into forgettable bread and butter roles. Her role here is one of the few times that she was allowed to play anything that had some character to it.

The production of Brainstorm was crippled following lead actress Natalie Wood’s accidental drowning in 1982 towards the end of shooting. Although there is reportedly only one scene that this affected, MGM wanted to dump the film but Trumbull managed to salvage it with the help of an insurance policy from Lloyd’s of London. Wood’s performance is cut around well and the film is a fitting tribute to her career. Wood’s death gave the themes of the film an unexpected poignancy, You cannot help but draw parallels between Christopher Walken’s desire to defy official orders and hack into the system to view the forbidden tape of Louise Fletcher’s death and Douglas Trumbull’s persistence to get Brainstorm seen despite the studio’s desire to shut it down and write off losses following Wood’s death.

Subsequent to Brainstorm, Douglas Trumbull abandoned special effects and feature filmmaking altogether. For many years, his work concentrated on the long-planned Showscan process – a series of short films made in 70mm and projected at 60 frames per second to be shown in specially designed theatres. Trumbull’s Showscan short films include New Magic (1983), Big Ball (1983), Let’s Go (1985), Leonardo’s Dream (1989) and To Dream of Roses (1990). Alas Showscan never caught on and was eventually co-opted by the IMAX process, with Trumbull later becoming a vice-chairman of the IMAX corporation. Trumbull also directed Universal Studios Back to the Future ride in 1991. The original idea for the film came from Bruce Joel Rubin who went on to write/direct a number of other films that concern themselves with death and the afterlife – Ghost (1990), Jacob’s Ladder (1990) and My Life (1993). Trumbull also produced The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then The Bigfoot (2018)..

Trailer here