USA. 2002.

Crew

Director – Simon Wells, Screenplay – John Logan, Based on the 1960 Film Written by David Duncan and the Novel by H.G. Wells, Producers – Walter F. Parkes & David Valdes, Photography – Donald McAlpine, Music – Klaus Bardelt, Visual Effects Supervisor – James E. Price, Visual Effects – Cinesite (Supervisor – Thomas J. Smith), Digital Domain (Supervisor – Erik Nash), Illusion Arts Inc (Supervisors – Syd Dutton & Bill Taylor) & Industrial Light and Magic (Supervisor – Scott Squires), Special Effects Supervisor – Matt Sweeney, Makeup Effects – The Stan Winston Studio (Supervisor – Greg Fiegel), Uber Morlock Created by KNB EFX Group Inc (Supervisor – Greg Nictoero), Production Design – Oliver Scholl. Production Company – Warner Bros/DreamWorks SKG

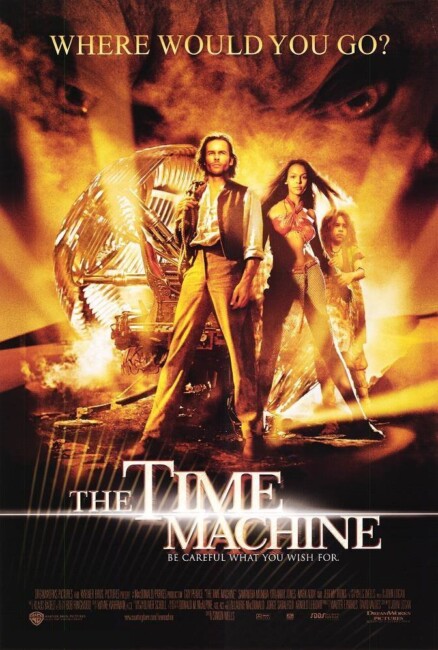

Cast

Guy Pearce (Dr Alexander Hartdegen), Samantha Mumba (Mara), Omero Mumba (Kalen), Orlando Jones (Hologram), Mark Addy (David Philby), Jeremy Irons (Uber-Morlock), Sienna Guillory (Emma), Phyllida Law (Mrs Watchit), Max Baker (Mugger)

Plot

In the early years of the Twentieth Century, Alexander Hartdegen, an associate professor at Columbia University, proposes to his girlfriend Emma, only for her to be shot moments later by a mugger. Afterwards, Alexander withdraws from the world and obsessively buries himself in his work. Four years later, he unveils a time machine that he has constructed. On its maiden voyage, he travels into the past and tries to rescue Emma before the mugging – only for her to be killed by a horse carriage moments after. Trying to understand why he cannot change the past, Alexander travels into the future, witnessing the marvels of the 21st Century. Following the destruction of The Moon, he travels into the year 802,701 where he encounters the remnants of humanity, the placid Eloi, who live a tranquil life on a village along the side of a cliff. As Alexander is drawn to the English-speaking Eloi woman Mara, the village comes under attack by the brutish Morlocks who capture the Eloi as food. Refusing to accept the Eloi’s calm acceptance of their fate, Alexander ventures down into the Morlock underground stronghold to rescue Mara.

The H.G. Wells novel The Time Machine (1895) is a genuine science-fiction classic. There had been works of time travel written before it but all of these were written as fantasy where the traveller moves through time either in a dream or via a convenient timeslip plot device. With The Time Machine, H.G. Wells created the concept of the time machine – an idea that has become a staple genre trope since. Moreover, H.G. Wells’s concept of a time traveller freely ranging throughout vast epochs of time and his wondrous description of watching time speeded up is something that caught a chord in the public imagination. Among the many other classics that H.G. Wells wrote in his lifetime, The Time Machine is invariably regarded as his finest work.

The book was filmed as The Time Machine (1960), a rich period classic from George Pal, which invoked the journey through time with an appropriate sense of wonder, although faltered somewhat in dulling Wells’s future social satire down to two-fisted adventure. The book was remade as a tv movie The Time Machine (1978), a cheap and shabby version that modernises the story.

Since the 1960 film, the H.G. Wells novel has entered into the pantheon of classic literary status. There have been various sequels, comic-book adaptations, illustrated young reader versions, stage adaptations (although not yet the musical adaptation the film mentions) and works like Christopher Priest’s The Space Machine (1976) wherein Wells’s time machine visits the Mars of his War of the Worlds; K.W. Jeter’s Morlock Nights (1979), which unleashes the Morlocks in Victorian England; and Stephen Baxter’s The Time Ships (1995) with the time traveller and a Morlock companion travelling through an amazing series of time paradoxes and alternate timelines, eventually all the way back to the origin of the universe; not to mention films like Time After Time (1979), which began the cliche of H.G. Wells being his own time traveller.

There was also this remake, a lavishly mounted co-production between Warner Brothers and DreamWorks SKG, with top effects houses like Digital Domain and Industrial Light and Magic on board. Not unexpectedly, the remake becomes a distinctly postmodern adaptation that not only adapts the story but also includes plenty of Wellsian margin references throughout, including a portrait of the man that sits in the hall outside Guy Pearce’s lab and an amusing holographic display at the futuristic New York public library that recounts the history of the novel and various adaptations of it.

Of course, the remake’s one stunt-casting coup is that it managed to net Simon Wells, the great-grandson of H.G. Wells, as director. Previously, Simon Wells had worked as an animation director, co-directing the likes of An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991), We’re Back! A Dinosaur’s Story (1993) and The Prince of Egypt (1998) and solo directing Balto (1995), all under the aegis of Spielberg at Amblin and DreamWorks. The Time Machine was Simon Wells’s debut as a live-action director. Simon Wells’s presence affords the film an authentic seal of legitimacy that no money or endorsement could easily buy. (Although the seal of approval from the Wells estate may not be that great a thing – they did after all approve The Shape of Things to Come (1979), which is possibly the worst ever film adaptation of an H.G. Wells work).

While The Time Machine 2002 appears to be making a concerted effort to appeal to Wellsian purism, the film is considerably more philistine than it wants us to think it is. Sadly, the end credits inform us that it has not been adapted from the H.G. Wells novel but rather from the David Duncan screenplay for the 1960 film. Considering that most Wellsian purists regard the 1960 film as having badly bluntened the book, this is doubly disappointing – it is like someone trying to write a book review in English class by only seeing the film adaptation of a classic.

Many aspects from the 1960 film have been retained – such as the image of watching the passing of history via the speeded-up change of fashions in a dress shop opposite the time traveller’s house, and scenes with the time traveller stopping off in the midst of World War III or where he finds an information source that recounts the fall of civilisation. Like the 1960 film, the remake also dumps the darker aspects of the novel – the social satire of the Morlock/Eloi relationship that H.G. Wells saw as indicative of exploitative relationship between the bourgeoisie and working classes, and the end where the time traveller travels forward to visit the far flung future and sees humanity’s finally evolved form as a crustacean species and the end of the world.

The script comes for the remake from John Logan, who was considered a hot new screenwriter on the backs of the high-profile likes of Any Given Sunday (1999), Gladiator (2000) and went on to the likes of The Last Samurai (2003), The Aviator (2004), Hugo (2011), Rango (2011) and Skyfall (2012), as well as several less-than-inspiring genre entries with Bats (1999), Star Trek: Nemesis (2002), Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas (2003), Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007), Spectre (2015) and Alien: Covenant (2017).

John Logan adds many things to H.G. Wells. For one, he transplants the story’s setting from Victorian England to New York – although it is hard to fathom why. It can hardly be the usual business of it making it more appealing to American audiences and their inability to understand foreign accents as the film then turns around and, despite the American setting, puts Brits in supporting parts of Philby and the time traveller’s housekeeper, casts Australian Guy Pearce as the time traveller and Irish-African singer Samantha Mumba as the Eloi love interest.

Most notable of the changes is the elimination of the dinner party framing device at the start of the book and 1960 film and its replacement with an ungainly motivational backstory where we learn that the time traveller’s fiancée was killed by a mugger and that his real reason for building the time machine was to go back and prevent this from happening. It is ungainly, chiefly because it adds 20 minutes of exposition before we come to the parts where the 1960 film and the book start – the journey into the future. It feel like it does not belong, that it has only been grafted on to give cod Hollywood psychological depth to the story.

This version also expends more depth on the Eloi culture, adding a nod toward future linguistic evolution and the interesting notion that humanity of the future has evolved darker skin pigmentation. The most interesting parts of the film are when the script starts to develop the Morlocks out as more than traditional cannibalistic Troglodytes and introduces Jeremy Irons as the Morlock king bee. The scene where time paradox is invoked to explain the time traveller’s inability to change the past is this film’s single most intelligent and interesting addition to the original story.

Ultimately, The Time Machine 2002 feels like an adaptation of the story that has disappeared beneath the lavish over-production of the modern effects blockbuster. Everywhere the budget makes itself conspicuously felt – extravagant period reconstructions of New York streets and city stretching as far as the eye can see, the Eloi village built in pods hanging from a cliff-face, the expansive Morlock caverns. The film is pumped up with action sequences featuring animatronic Morlocks rampaging through the Eloi camp, fights around the weather vane memorial and a big climactic destruction of the Morlock complex.

The simple telling of the story feels dogged by a constant straining for size and effect. It is not merely enough, for instance, to have Guy Pearce and Jeremy Irons fight it out – they have to do so hanging in and around the bubble of the time machine as it speeds through time. Not far underneath the basic elements of the H.G. Wells story, this is a film whose only purpose is to try and make people go ‘wow’ every few minutes – certainly the adherence to Wells gives it far more substantial story than some recent effects blockbusters of the moment, but it still feels like CGI wonderment for the sake of it.

This is most noticeable when it comes to the classic scene from the 1960 film of the speeded-up journey through time seen from the time traveller’s point-of-view, which now comes with vines creeping up across the conservatory window and the house and city being rebuilt around him, while the camera pulls out into Earth orbit to show commercial planes touching down on the Moon. It is impressive but the sad truth is that CGI wonderment has become such a routinely banal thing by sheer overkill that it is now merely a trick effect, not a wondrous and magical experience the way the far more technically primitive equivalent was in the 1960 film.

Director Simon Wells subsequently returned to animation and went onto make the motion-capture animated Mars Needs Moms (2011).

(Nominee for Best Makeup Effects and Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 2002 Awards).

Trailer here