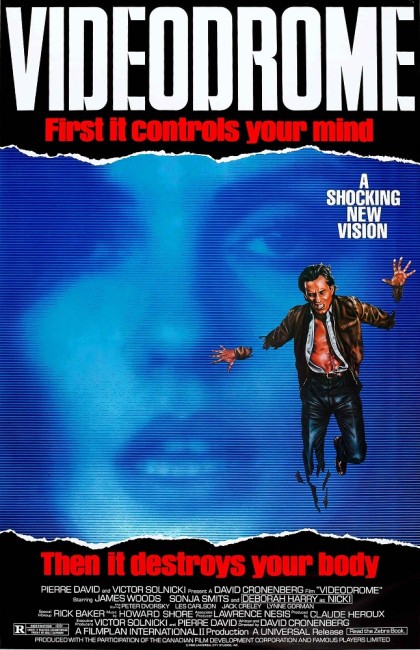

Canada. 1983.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – David Cronenberg, Producer – Claude Heroux, Photography – Mark Irwin, Music – Howard Shore, Video Effects – Michael Lennick, Mechanical Effects – Bill Sturgeon, Special Effects – Frank Carere, Makeup Effects – Rick Baker, Art Direction – Carol Spier. Production Company – Filmplan International.

Cast

James Woods (Max Renn), Deborah Harry (Nicki Brand), Peter Dvorsky (Harlan), Sonja Smits (Bianca O’Blivion), Les Carlson (Barry Convex), Jack Creley (Professor Brian O’Blivion), Lynne Gorman (Marsha)

Plot

Max Renn, manager of an X-rated cable-tv station, picks up a broadcast from a pirate-channel show called ‘Videodrome’, which specialises in sadomasochism. Fascinated, Renn sets out to find out more about ‘Videodrome’ but is warned about further involvement. He sleeps with radio show psychologist Nicki Brand who becomes fascinated with ‘Videodrome’ when she sees his tapes. Nicki vanishes after auditioning for ‘Videodrome’, later to reappear in broadcasts. The quest leads Renn to media guru Brian O’Blivion who no longer appears by anything other than videotaped message. O’Blivion tells Renn that the Videodrome signal has created a tumor in Renn’s brain that blurs the distinguishing line between reality and tv. Soon unable to distinguish what is hallucination and what is not, Renn becomes an organic video-recorder that the mysterious controllers of ‘Videodrome’ reprogram as an assassin.

Canada’s David Cronenberg is one of the most unique and original voices working within the sf/horror genre. After a couple of obscure arty science-fiction films which nobody saw – Stereo (1969) and Crimes of the Future (1970) – David Cronenberg first emerged on the scene with a handful of potent B-horror movies – Shivers/They Came from Within/The Parasite Murders (1975) and Rabid (1977) – then worked his way up toward better-budgeted hits like The Brood (1979), Scanners (1981), The Dead Zone (1983) and The Fly (1986).

Even when working in the medium of B-budget horror, David Cronenberg’s films are lit up with an astounding number of metaphors where the human body is seen as a playground between repression, desire and science. The late 1980s and beyond has seen Cronenberg push boundaries (as well as easy pigeonholing as a genre director) as far as possible with astonishing and perverse works like Dead Ringers (1988), Naked Lunch (1991), M. Butterfly (1993) and Crash (1996). (See below for a full list of David Cronenberg’s films).

Videodrome was the most conceptually daring film David Cronenberg had dared to foist on audiences up until that point. Videodrome brims over with ideas and meditations about the media, all shot through with Cronenberg’s ideas about mutable flesh. Understandably, Videodrome was a financial failure in theatres. (Although it swiftly garnered a cult reputation on the video circuit – something that only makes the film’s thematic issues seem even more ironic).

The world of David Cronenberg’s films is an almost satirically exaggerated Manichean one – one where the human body is a battleground caught between good and evil. In Cronenberg’s films, flesh is always mutating and becoming a form of expression for repressions, and there is an erotic connection between flesh and science where humans willingly embrace and commingle with technologies in a brand new form of expression.

Videodrome is like a dark satire on 1970s media guru Marshall McLuhan (who was, like Cronenberg, also a Canadian). In Videodrome, Cronenberg melds Marshall McLuhan’s theories about “the medium becoming the message” and television’s shaping of human conception (a little phrase McLuhan invented called “the media landscape”) with his own recurrent imagery of malleable flesh in a dazzling melange. McLuhan is wittily incarnated in Videodrome‘s guru Brian O’Blivion, who only lives as a videorecorded image and comes out with lines like “TV is reality and reality is less than tv.”

People rarely see the dyer-than-dry sense of humor that lurks in Cronenberg’s films. The film here is filled with arcane jokes – there is the Cathode Ray Mission, a soup kitchen run by O’Blivion’s daughter that instead of offering food allows homeless access to tv so they can be rehabilitated. “It’s not a style,” she says of the down-and-outs we see, “it’s a disease forced upon them by their lack of access to a cathode tube,” and indeed we later see one of their rehabilitated playing an organ grinder tv on a street corner, asking for money to keep his tv in batteries.

In another witty aside, Cronenberg takes the old adage about tv being a nipple to the ultimate conclusion and there is an astounding moment when Deborah Harry’s lips fill a tv screen and James Woods bows submissively before it, allowing the tv screen to encase his head. Not even satisfied with that metaphor, Cronenberg pushes it even further, turning James Woods into a living receptacle, having videocassettes inserted into his stomach. Rick Baker’s effects work here is truly amazing – the scene where James Woods finds the opening in his stomach and pokes a handgun in out of curiosity only to lose it is one of the most creepily queasy moments in modern horror.

Videodrome brims with such an audacious collation of ideas that trying to understand it is like trying to grab the proverbial greased pig. The film could almost be a satire on the conservative assertions that televised violence affects people’s behaviour. James Woods offers up arguments in favour of televised sublimated violence – “Better on tv than the streets” – and its lack of affect but contrarily is later seen looking for material that is less boring, something that will stir people up.

Similarly, James Woods is no standard horror movie hero – he seems a passive victim, more of a couch potato who sits back with indifference to things and in so doing has his entire view of reality and then his body taken over by television to become a living videocassette that is reprogrammed to go out and kill. You could argue that David Cronenberg is offering a conservative argument about televised violence and critical theories about television shaping attitudes and perceptions – that moral apathy and passivity inures one and in so doing they become blank for whatever messages televised programmers want to assert.

Eventually however, Cronenberg’s wild leaps and bounds of imagination get away from him, drowning out the plot altogether. The ending is an anti-climax where all it seems he can do to bring the tangled skein to a conclusion is to kill the character off rather than give the plot any easy ending. Videodrome is nevertheless a dark and disturbing film with a great many things to say, in a not necessarily always coherent way, about television and catharsis. Howard Shore delivers a deep, sinister basso score that underlines the dark relentlessness of the vision. Far removed from the relative ease and lightness of more commercial films like Scanners and The Fly, Videodrome is one of David Cronenberg’s ambiguous masterpieces.

Cronenberg later revisited many of the themes of Videodrome – corporations warring over control of reality; participants caught up in hallucination; organic meldings of technology and flesh, including a literal ‘hand-gun’ – albeit less interestingly – in the Virtual Reality film eXistenZ (1999).

David Cronenberg’s other films are:– Stereo (1969), a little-seen film about psychic powers experiments; Crimes of the Future (1970), a film about a future where people have become sterile; Shivers/They Came from Within/The Parasite Murders (1975) about sexual fetish inducing parasites; Rabid (1977) about a vampiric skin graft; The Brood (1979) about experimental psycho-therapies; Fast Company (1979), a non-genre film about car racing; Scanners (1981), a film about psychic powers; The Dead Zone (1983), his adaptation of the Stephen King novel about precognition; The Fly (1986), his remake of the 1950s film; Dead Ringers (1988) about two disturbed twin gynaecologists; Naked Lunch (1991), his surreal adaptation of William S. Burroughs’ drug-hazed counter-culture novel; M. Butterfly (1993), a non-genre film about a Chinese spy who posed as a woman to seduce a British diplomat; Crash (1996), Cronenberg’s adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s novel about the eroticism of car crashes; eXistenZ (1999), a disappointing film about Virtual Reality; Spider (2002), a subjective film takes place inside the mind of a mentally ill man; the thriller A History of Violence (2005) about a hitman hiding under an assumed identity; Eastern Promises (2007) about the Russian Mafia; A Dangerous Method (2011) about the early years of psychotherapy; Cosmopolis (2012), a surreal vision of near-future economic collapse; the dark Hollywood film Maps to the Stars (2014); Crimes of the Future (2022) set in a future world of surgical performance art; and The Shrouds (2024) about the development of a technology that places videocameras inside graves. Cronenberg has also made acting appearances in other people films including as a serial killer psychologist in Clive Barker’s Nightbreed (1990); a Mafia hitman in To Die For (1995); a Mafia head in the vampire film Blood and Donuts (1995); as a member of a hospital board of governors in the medical thriller Extreme Measures (1996); as a gas company exec in Don McKellar’s excellent end of the world drama Last Night (1998); a priest in the serial killer thriller Resurrection (1999); and as a victim in the Friday the 13th film Jason X (2001).

Trailer here