Denmark/Sweden/France/Germany. 2011.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Lars von Trier, Producers – Meta Louise Foldager & Louise Vesth, Photography – Manuel Alberto Claro, Visual Effects Supervisor – Peter Hjorth, Visual Effects – Filmgate, Kingz Entertainment, Klippengangen ApS & Pixomondo, Special Effects Supervisor – Hummer Høimark, Production Design – Jette Lehman. Production Company – Zentropa Entertainment/Film I Väst/Memfis Film International/Zentropa International Sweden/Slot Machine Sarl/Liberator Productions Sarl/Zentropa International Köln GMBH/Arte France Cinema/SVT/Canal +/Centre National du Cinema et de L’image Animee/Cinecinema/Edition Video Potemkine Films et Agnes B.DVD/Nordisk Film Cinema Distribution.

Cast

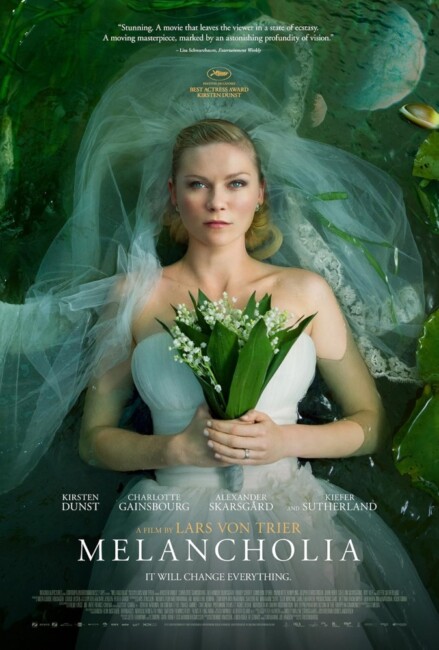

Kirsten Dunst (Justine), Charlotte Gainsbourg (Claire), Kiefer Sutherland (John), Alexander Skarsgard (Michael), Stellan Skarsgård (Jack), John Hurt (Dexter), Charlotte Rampling (Gaby), Brady Corbet (Tim), Cameron Spurr (Leo), Jesper Christensen (Little Father), Udo Kier (Wedding Planner)

Plot

It is the wedding day of Justine and Michael. John, the husband of Justine’s sister Claire, has laid the event out at great cost. However, as the ceremony progresses, Justine begins to feel increasingly more unhappy. She deliberately has sex with a younger man and causes Michael to walk out. She then quits her newly appointed job as a marketing firm art director by insulting her boss. Afterwards, Justine comes to stay with Claire and John in a severely depressed state. At the same time, Claire has growing anxiety about Melancholia, a newly discovered planet that was hidden behind the sun and has now emerged on an orbit that will pass close by the Earth. John’s scientists have assured them that it will not collide. However, as it becomes increasingly apparent that Melancholia is going to impact with the Earth, Claire struggles to stop herself surrendering to despair and hopelessness.

I have said it before and shall say it again – I think Lars von Trier is one of the unparalleled geniuses of modern cinema. Von Trier is someone who is constantly reinventing what he does – he made a work of extraordinary visual artifice with the stylistically daring Zentropa/Europa (1991) and then followed it by repudiating all of that and creating a new movement that deliberately eschewed any form of artifice in favour of raw, handheld camerawork, natural settings and lack of canned dramatics with the Dogme 95 school, out of which he made works such as Breaking the Waves (1996) and The Idiots (1998). He has a frequently dark sense of humour – The Kingdom (1994), The Boss Of It All (2006) – but will follow this with works that place his audience through an extraordinary emotional ringer with the likes of Breaking the Waves and Dancer in the Dark (2000).

Von Trier is a constant trickster and agent provocateur who enjoys pushing boundaries and inflaming people – The Idiots, a film about people who play at being intellectually handicapped for the sake of exposing social hypocrisy, his unfinished trilogy consisting so far of Dogville (2003) and Manderlay (2005) that is deeply critical of social values in America; and Nymphomaniac (2013) wherein a woman recounts tales of her sexual expoits.

In 2006, von Trier suffered from an acute state of depression and confessed that he believed that he would never be able to make another film again. After sufficient therapy, he was able to channel his feelings onto film, resulting in Antichrist (2009) – a work about the collapse of a marriage into emotional trauma and eventual outright torture. When, at the time of Antichrist, von Trier announced Melancholia and stated that it was his venture into making an epic Roland Emmerich-styled science-fiction film about the end of the world, this seemed either von Trier reinventing his own style again or toying with his audience.

As becomes apparent, Melancholia, while nominally similar to a Roland Emmerich film on many levels, is yet another facet of von Trier’s black depression. If you point to a similar film such as 2012 (2009), there Roland Emmerich directs in big dramatic cliches with characters of zero depth, only a successive series of giant-sized spectacle and effects scenes. Von Trier certainly has several visual effects houses and a star cast on board – names like Kirsten Dunst, Kiefer Sutherland, John Hurt, Charlotte Rampling and both Skarsgårds, Stellan and his son, the increasingly rising Alexander – but his film remains solidly rooted in emotional rawness. Von Trier strips everything away until the film is about the emotions of the characters with the end of the world as a looming backdrop. There are special effects scenes but the drama never moves beyond the gardens and golf course of a country chateau. A closer comparison might be to the spectacle and effects-stripped end of the world drama Last Night (1998).

Melancholia reminds a good deal of another film that came out the same year with the modest indie hit of Another Earth (2011). Both films are about the appearance of another planet heading towards Earth on a close pass by. Both are also films that come from places that do not normally produce an abundance of science-fiction films – the US indie cinema scene in Another Earth, the European festival/arthouse circuit where most of Lars von Trier’s work plays to. They are works that both use epic astronomical events as a macrocosmic mirror of character drives on a personal level – one woman seeking redemption for wrongdoings of her past in Another Earth, a woman trying to cope with overwhelming despair in Melancholia. You could maybe also draw a connection to Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011), which came out around the same time and also saw cosmological teleology as a macrocosmic mirror for the turbulent emotional fractures within a family growing up in the 1950s.

This does bring one to one of the chief bugbears about both Another Earth and Melancholia – and that is they are primarily and foremost arthouse and indie films. They do not seem interested in their science-fictional premises in terms of credible science. In astronomical terms, both films have a fundamentally implausible premise – a newly discovered planet of the solar system behaving in very un-planet-like ways. If such a large mass were in close orbit, even hidden behind the sun, its gravity signature would have been detected before now by astronomers.

Secondly, planets do not spontaneously wander out of their orbits. The graphic diagram we are shown seems to indicate that Melancholia is following its natural orbit, which one is prepared to give the film even though unlikely (and would mean it would have detected by telescopes before now) – however, Melancholia then does the extremely un-planet-like thing of passing the Earth by before suddenly reversing direction to return and impact. Planets are moved by gravity – they fall into an orbiting rotational path around the heaviest mass, which in the Solar System would be the Sun – and lack any form of independent propulsion. The only thing that would cause them to move would be a far larger source of gravity, which would mean that there would have to be two separate sets of influences far greater than the Sun drawing Melancholia in its respective different directions. This however would surely also be affecting the Earth.

The other big bugbear, just like Another Earth, is that the nearness of Melancholia would be having catastrophic effects on The Earth. If you consider the size that The Moon is and how it influences Earth’s tidal patterns, a planet that is so near that it fills the entire sky would be causing vast tidal waves, not to mention dragging on tectonic plates, causing earthquakes and volcanic activity. In this respect, the 2012-type spectacle of disaster would be the more likely depiction of what would be happening.

Where Another Earth allowed its heroine her redemption, where The Tree of Life was eventually about seeking recovery from loss, Melancholia is utterly bleak and pessimistic. When Kirsten Dunst says with vehement bite: “The Earth is evil. We don’t need to grieve for it,” the effect is astonishing. Melancholia is divided into two parts – the first named after Kirsten Dunst’s Justine, the second Charlotte Gaisnbourg’s Claire. The first section does not concern itself too much with the approaching planet and is about Kirsten Dunst’s increasing sense of unhappiness on her wedding day. We never find out what it is that she is unhappy about, we see the rifts in the family (the great Charlotte Rampling is at her acid-dripping best and steals the show by pouring constant scorn on the wedding), Kirsten’s detachment and desire to escape, eventually culminating in her repudiation of both her husband and employer.

The section irritates because – just like in Antichrist – we are never privy to the processes that go on inside Kirsten Dunst’s head, it seems about someone who has a generalised but unspecified unhappiness with the life of privilege and family around her. You keep waiting for Lars von Trier to take us deeper but it is like Charlotte Gaisbourg’s descent into madness in Antichrist – something that occurs without any window in on the psychological processes. It almost seems as though von Trier has reached a point where he sees the depression that affected him as so overwhelmingly vast that it cannot be reduced to something as trivial as explanations and where the end of the world seems only befitting such profound and devastating sense of nihilism. Surely, on some deeper psychological level, a welcoming of the destruction of everything seems indicative of an unspoken desire for self-extinguishment on von Trier’s part.

I liked Melancholia but didn’t love it. Certainly, many others did and it was nominated for the Palme d’Or at Cannes with Kirsten Dunst winning Best Actress. I find Lars von Trier’s last two films, Antichrist and this, where he has explored his depression, to be relentless. I am not against bleak films by any means. In these cases though, they are films where von Trier has stripped all other things away, often drama and any psychological explanations of his character’s motives, and presented raw emotion on screen. This I get but I kind of wish I’d also be able to figure what either film is saying in terms of where each of the characters are coming from and their reasons for descending as they do. You cannot decry an artist who is in the process of exploring new territory and it will be interesting to see where Lars von Trier arrives at on the other side of this journey. However, I think I liked von Trier more in the days where he was making experiments in style, being a provocateur determined to upset the establishment and especially in drawing out works of extraordinary emotional power.

Lars von Trier’s other films of genre interest as a director are:– the decayed future film noir The Element of Crime (1984); Epidemic (1987), a peculiar meta-fiction about filmmakers making a film about a plague and hypnotism; the black comedy tv mini-series’ The Kingdom (1994) and The Kingdom II (1997) set in a haunted hospital, which were both cinematically released in the West; Breaking the Waves (1996), an emotionally devastating film about a woman’s masochistic sacrifices for her husband, which eventually arrives at a fantastic climax; Antichrist (2009), a film about grief that spirals into madness and extreme torture scenes; the serial killer film The House That Jack Built (2018); and The Kingdom: Exodus (2022). von Trier was also Executive Producer on Kingdom Hospital (2004), the Stephen King scripted, US tv series remake of The Kingdom. von Trier’s production company Zentropa Entertainments have also produced and co-produced numerous other films. Of genre note are the Icelandic Magical Realist quest Cold Fever (1995); the Swedish fairytale The Glassblower’s Children (1998); the surreal Old Dark House thriller Impotence/Powerlessness (1998); Possessed (1999), a plague film about The Devil returning at the Millennium; Kat (2001), a horror film about a possessed cat; the Dogme film Truly Human (2001) about an imaginary man becoming real; The Last Great Wilderness (2002), a Gothic thriller set in the Scottish Highlands; Thomas Vinterberg’s near-future romance It’s All About Love (2003); In Your Hands (2004), a Dogme film about miracle healing prison inmate; the remarkable puppet fantasy Strings (2004); the ghost story Behind External Calm (2005); the dark reality-twisting Norweigian film Next Door (2005); Princess (2006), an animated film about an anti-porn vigilante; the fantasy Island of Lost Souls (2006); the horror film Echo (2007); the satirical dystopia How to Get Rid of Others (2007); Through a Glass Darkly (2008) about a girl receiving a mysterious visitation; the animated Dystopian film Metropia (2009); and Perfect Sense (2011) set in a world where people are losing their sensory perception.

(Nominee for Best Supporting Actress (Charlotte Rampling) at this site’s Best of 2011 Awards).

Trailer here