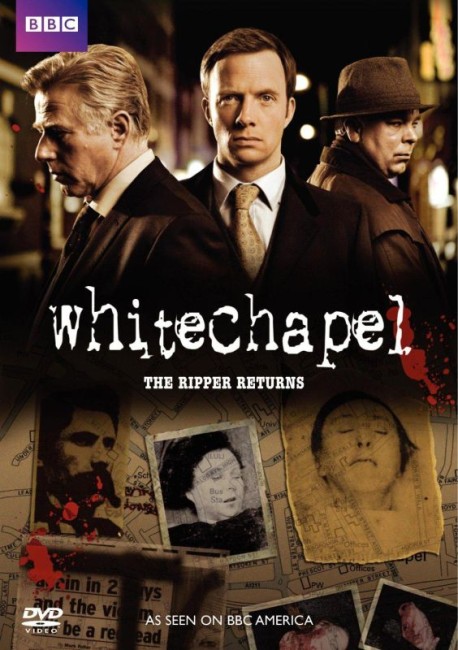

UK. 2009.

Crew

Director – S.J. Clarkson, Teleplay – Ben Court & Caroline Ip, Producer – Marcus Wilson, Photography – Balazs Bolygo, Music – Ruth Barrett, Production Design – Martyn John. Production Company – Carnival Film & Television Limited.

Cast

Rupert Penry-Jones (Detective Inspector Joseph Chandler), Phil Davis (Detective Sergeant Ray Miles), Steve Pemberton (Edward Buchan), Christopher Fulford (Detective Constable Fitzgerald), Johnny Harris (Detective Constable Sanders), Sam Stockman (Detective Constable Kent), George Rossi (Detective Constable McCormack), Alex Jennings (Commander Anderson), Paul Hickey (Dr David Cohen), Sophie Stanton (Mary Bousfield), Ben Loyd-Holmes (Private John Leary), Constantine Gregory (A.C. Maduro), Branko Tomovic (Antoni Pricha), Sally Leonard (Frances Cole), Dutch Dore-Boize (Robert Lees)

Plot

Joseph Chandler, a rising Detective Inspector on the London police force who is seen as having a high-profile career ahead of him, is appointed head of the detective division in Whitechapel. Chandler’s fastidiousness soon conflicts with the rough working class ways of the men under his command. Chandler’s first investigation is the body of a woman found slaughtered in a courtyard near the scene of a fire. Afterwards Chandler is approached by Edward Buchan, a Ripperologist who has published a book on the Jack the Ripper murders and runs a tour of the sites where the killings happened. Buchan claims that the body was found at one of the Ripper murder sites and has been killed in a way that is identical to the first Ripper victim. Further investigation convinces Chandler that Buchan may not be a crackpot and he goes out on a limb, risking ridicule and his career, to follow this theory. He is proven right as a further body is found slaughtered at another Ripper murder site identical to the way that the Ripper killed his victim. A furore erupts after one of the detectives leaks this to the press in an effort to humiliate Chandler. As the killings continue, Chandler realises that he must solve the identity of the original Jack the Ripper killings in order to find who the modern copycat is.

The Jack the Ripper case casts a great shadow over modern horror and crime fiction. Jack the Ripper was to all accounts the first truly modern serial killer (although other claimants exist) well before the term was ever coined. There has been an enormous amount of speculation – libraries of books written on the subject – about the identity of The Ripper. What is the most fascinating about this is that nobody was ever conclusively found to be responsible. This has not stopped a great deal of wild and fanciful speculation about the subject among modern Ripperologists who have meticulously attempted to dig up evidence for and against varying theories and suspects. A recent trend has been attempting to analyse the Ripper killings in terms of modern crime detection and serial killer profiling. There is a great deal of speculation about how modern forensics may have helped in solving the case – fingerprinting as a criminal detection technique was not even introduced by Scotland Yard until a decade after the killings, for instance – although with more than a century since the killings occurred, remaining evidence that would conclusively sway the case is almost certainly long gone. Thriller writer Patricia Cornwell did however make a fascinating (if inconclusive) non-fiction attempt to forensically pinpoint the Ripper in her book Portrait of a Killer – Jack the Ripper: Case Closed (1992).

None of this has stopped a great deal of continuing speculation on cinema and tv screens. There are a number of straight tellings of the Jack the Ripper case that include The Lodger (1944), Room to Let (1950), Man in the Attic (1953), Jack the Ripper (1959), the Spanish Jack the Ripper of London (1971) with Paul Naschy, Jess Franco’s Jack the Ripper (1976) with Klaus Kinski, Jack the Ripper (tv mini-series, 1988) starring Michael Caine, The Ripper (1997) and the Alan Moore graphic novel adaptation From Hell (2001) with Johnny Depp. What is notable among most of these is their lack of focus on the basic facts of the case and their dealing instead with some of the more fanciful and way-out Ripper theories – like the absurd Prince Albert Victor and Royal Freemason Conspiracy theories (something the mini-series here appropriately calls “the biggest load of bunkum to ever taint Ripperology”) or invented suspects. More prevalent have been speculative treatments, including the likes of:- having the contemporary but fictional figure of Sherlock Holmes solve the mystery in A Study in Terror (1965) and Murder By Decree (1979); the Ripper being an alien spirit that possesses Scotty in Star Trek‘s Wolf in the Fold (1966) and with similar stories occurring in episodes of Kolchak: The Night Stalker (1974-5) and The Outer Limits (1995-2002); the Ripper being Dr Jekyll in both Dr Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971) and Edge of Sanity (1989); Jack the Ripper’s daughter featuring in Hands of the Ripper (1971); H.G. Wells and the Ripper travelling through time to the present day in Time After Time (1979) and its tv series remake Time After Time (2017), as well as a time-travelling Ripper appearing in episodes of tv series like Fantasy Island (1977-84), Goodnight Sweetheart (1993-9) and Timecop (1997-8); The Ripper having travelled out West in the Knife in the Darkness (1968) episode of the Western tv series Cimarron Strip (1967-8) and the film From Hell to the Wild West (2017);The Ripper being resurrected or copycated in the present day in The Ripper (1985), Bridge Across Time/Terror at London Bridge (1985), Jack’s Back (1988), Ripper: Letter from Hell (2001), Bad Karma (2002), The Legend of Bloody Jack (2007) and The Lodger (2009); a parody segment of Amazon Women on the Moon (1987) that speculates that the Ripper was in fact the Loch Ness Monster; the Babylon 5 episode Comes the Inquisitor (1995) that reveals the Ripper was taken up by aliens and redeemed; transposed to Gotham City in the animated Batman: Gotham By Gaslight (2018); even turning up as a character in the French animated film Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart (2013). Also of interest is the tv series Ripper Street (2012-6), a detective series set in London in the immediate aftermath of the Ripper killings.

Whitechapel offers up a fascinating modern interpretation. It becomes in many senses a meta-fictional Jack the Ripper story – it winds in a Ripperologist who runs a Ripper tour who alternately becomes a source of information and a suspect. It is the only Jack the Ripper-based work that can be said to have been filmed on the locations where the original events took place (or at least the modern equivalent of them – as the mini-series points out, only one of the locations is still standing). The mini-series’ writers have certainly researched their Ripperology. They know their theories and victimology well – even introducing Martha Tabram as a strong potential victim, as many Ripperologists do. The mini-series even goes so far as to give characters throughout the names of people around the periphery of the original Jack the Ripper case – the boyfriend of the first victim who is briefly suspected is named Robert Lees after the clairvoyant who contacted the police offering up ‘evidence’ as to the identity of the killer; the police woman Mary Bousfield who later becomes a victim is named after Martha Tabram’s landlord; and the last victim this Ripper targets is called Frances Cole after a non-canonical murder victim who may or may not have been killed by the Ripper.

The mini-series does introduce an interesting theory about what it calls the Double Event Night when The Ripper killed two victims Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes within three-quarters of an hour of each other. The universally accepted theory is that The Ripper was interrupted in the first killing and, with his hunger for the kill not slated, went onto find another victim. Contrarily, the mini-series introduces a new theory that one of the killings was a copycat. This is a completely new concept in Ripperology and something that one suspects has been invented by the mini-series for plot convenience – ie. to come up with a way around the logistics of the killer having to dump bodies at two murder scenes inside a short period without being caught by police who have staked the area out – than any credible existing theory.

Whitechapel is a fascinating work. I don’t know if it works as a great thriller on its own terms but it is carried a substantial part of the way by its premise. One of the more intriguing parts of the story is where Ripperologist Steve Pemberton tells Rupert Penry-Jones that to solve the modern case he has to solve the identity of the historical Ripper. Interestingly, Penry-Jones then sidesteps all of the major suspects and alights upon George Hutchinson, a witness who has been identified as a potential suspect on the grounds that he gave a suspiciously long and extremely detailed description of the man that was seen with Mary Kelly just before her death. The big disappointment of the story is that for all that Rupery Penry-Jones is urged to select a Ripper suspect, his choice never has any bearing on the way that the murders here are solved. Nor is the unveiling of the Ripper copycat’s identity as big as the mini-series leads up to, with the killer improbably having erased their identity and then killing themselves so that their crimes can fade into the unknown mystery of time just like the original. This is perhaps being a little too faithful to the events of the original Ripper case – it would have been nice if the writers had extended their speculations to choose a killer and made the revelation somehow relevant to the killer’s actions in the present.

The script sets up an interesting series of character conflicts. Rupert Penry-Jones is cast in the role of the rookie commander coming in to take charge of an unruly squad. The story plays this off in interesting ways. The impossibly handsome Penry-Jones is set up as a high-rising detective who is bookishly straight and, as becomes increasingly apparent throughout the series, fastidiously uptight to the point of possible psychological obsession – angrily remonstrating the men of the squad for the sloppiness, even their failure to wear ties, and is seen constantly concerning himself with cleanliness. This is contrasted with the men of the squad who are characterised as rough, crude and working class in tone. This makes the essential character conflict that drives the story one of Rupert Penry-Jones’s fastidiousness versus the uncouth men, of upper class snobbery vs working class vulgarity.

This divide is spearheaded by two fine performances. I have admired Rupert Rupert Penry-Jones previously as the lead in the fine British spy tv series Spooks (2002-11) but here he has taken on a role that makes him decidedly unlikable and non-sympathetic at times. Up against him is Phil Davis, an actor whose performances can sometimes take you aback – he seems to specialise in roles where he plays a thuggishly coarse individual, where his delivery frequently comes laced with an underlying nastiness. Where Rupert Penry-Jones plays against type and is not as likeably handsome as usual, so too does Davis, allowing the coarseness to even out to an agreeable and surprisingly decent character. One kept wondering how this conflict between uptight rookie and rough streetwise men related to the story, given the emphasis it is in the script. Eventually it is just a set-up for Penry-Jones to risk his promising career for the case and the well-worn theme of the rookie superior winning the trust of the men.

The last scene of the mini-series tends to suggest that everything has been set up for a potential ongoing series, although with the Jack the Ripper angle played out one is not sure how this would work with any great originality. A second three-part series was produced in 2010, although this was about the supposed resurrection of the crimes of the Kray Brothers and did not feature anything to do with Jack the Ripper. A third series in 2012 consisted of three two-part standard self-contained detective stories, while the fourth series in 2013 dealt with the activities of a cult of occult cannibals.

(Nominee for Best Original Screenplay at this site’s Best of 2009 Awards).