Crew

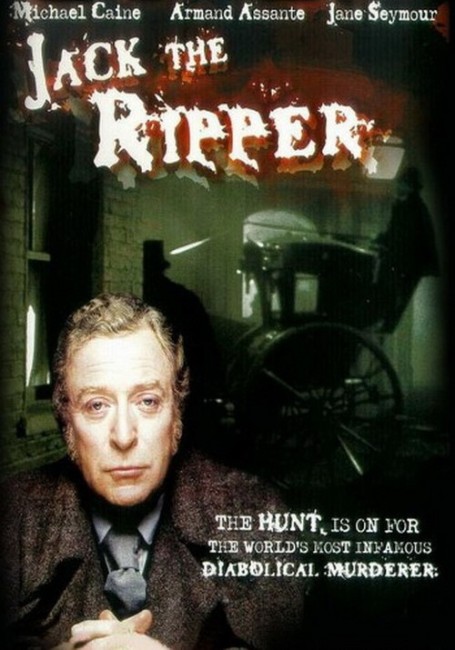

Director/Narrative Concept/Producer – David Wickes, Teleplay – Derek Marlowe & David Wickes, Photography – Alan Hume, Music – John Cameron, Prosthetic Makeup – Aaron Sherman & Maralyn Sherman, Production Design – John Blezard. Production Company – Thames/Hill-O’Connor Television/Lorimar Telepictures.

Cast

Michael Caine (Inspector Frederick Abberline), Lewis Collins (Sergeant George Godley), Ken Bones (Robert Lees), Armand Assante (Richard Mansfield), Michael Gothard (George Lusk), Ray McAnally (Sir William Gull), Jane Seymour (Emma Prentice), Jonathan Moore (Benjamin Bates), Hugh Fraser (Sir Charles Warren), Michael Hughes (Dr Llewellyn), George Sweeney (John Netley), Richard Morant (Dr Acland), Jon Laurimore (Inspector Spratling), Lysette Anthony (Mary Jane Kelly), T.P. McKenna (O’Connor), Gary Love (Derek), Edward Judd (Chief Superintendent Tom Arnold), Peter Armitage (Sergeant Kerby), Harry Andrews (Coroner Wynne Baxter), Susan George (Catherine Eddowes), John Normington (Dresser)

Plot

London, 1888. The city is rocked after the discovery of the slaughtered body of a prostitute in the Whitechapel area. As other bodies turn up, Scotland Yard’s Inspector Frederick Abberline is assigned to the case because of his knowledge of the area. The psychic Robert Lees comes to see them with claims of cryptic clairvoyant clues about who the killer is but Abberline is uncertain whether to believe Lees or regard him as a suspect. Certain that he is dealing with a madman, Abberline investigates the nature of madness. He becomes fascinated with American actor Richard Mansfield who is playing Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde on stage where connections seem to suggest Mansfield is a potential suspect. As further bodies accumulate, the Marxist George Lusk raises a mob in Whitechapel that targets anybody they consider suspicious. At the same time, clues seem to indicate that a Royal coach was seen in the area and rumours circulate that Prince Albert Victor has been dallying amongst the prostitutes of Whitechapel.

Jack the Ripper was a British tv mini-series that was made to celebrate the one-hundred year anniversary of the Jack the Ripper killings. Jack the Ripper was not the first serial killer but was the first to inflame the popular imagination and the first operating at times when there was something resembling a modern police force to investigate. Although there is some dispute as to how many murders there were, almost everybody agrees on the five canonical victims who were slaughtered in the impoverished Whitechapel district of London between August and November of 1888. The name Jack the Ripper was taken from numerous letters mailed to the press supposedly written by the killer who signed himself as such in one letter (although the letters were believed to be faked by a journalist). The Ripper was never caught, which is part of the fascination of the case. There have however been an enormous number of suspects, many those who fell under the police eye back during the day, many that have emerged out of historical research that has been conducted since. These range from the credible to more fanciful speculations and conspiracy theories – such as that the women were assassinated by a conspiracy of Freemasons to cover up a dalliance by a member of the Royal Family; that the Ripper was Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland (1865); and more recently, the James Maybrick diary hoax.

Up until the point this mini-series was made, there had been sporadic interest in Jack the Ripper on film. Alfred Hitchcock had made the classic The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927) and this was remade twice as The Lodger (1944) and Man in the Attic (1953) but these versions were so caught up in the censorship of the day that they could only refer to the victims as dancehall girls rather than prostitutes. There had been other films such as Jack the Ripper (1959) and Jack the Ripper (1976) but these created their own stories that only bore scanty resemblance to the facts of the case. The most prestigious version up until this point was Murder By Decree (1979), which had the fictional character of Sherlock Holmes investigating the case and followed the details reasonably closely, even if its resolution eventually went with the widely discredited Royal Freemason Theory (more on this below). It should be noted up until this point that Murder By Decree was the only version to name its Ripper as anyone who has been associated with the real Ripper investigations in real life. (See bottom of the page for other Jack the Ripper films and tv series).

The upshot of this was that the Jack the Ripper tv mini-series was widely perceived as being the work that offers the definitive depiction of the case – and still is in many quarters, although has been superseded somewhat by the Johnny Depp starring From Hell (2001), which offers an equally fictionalised account of events. To this extent, the mini-series consciously made a sales pitch to audiences that it was telling an authentic account and providing a definitive solution. The opening credits offers up a lengthy preamble that claims: “Our story is based on extensive research, including a review of the official files by special permission of the Home Office and interviews with leading criminologists and Scotland Yard officials.” In interviews, director/writer David Wickes claimed that they had uncovered new evidence but was later forced to retract these claims under pressure from Ripperologists to front up and show what he had.

To all of this, one can only say “bullpoppy.” Certainly, you have to credit the mini-series in many respects – it has done its research and adheres to the details of the case more so than any other work up to that point. It names the canonical victims, has actors playing the actual police investigators and coroners, names various witnesses and conducts an approximation of the various crime scenes, even casts an actor who bears a reasonable likeness to Lord Salisbury, the Prime Minister of the day. On these grounds, there is little that one can fault about the mini-series. However, on a dramatic level the story is almost a complete fiction. Or perhaps more to the point, it abandons all interest in depicting the canonical Ripper suspects and makes a beeline for the lurid and sensationalistic. The three suspects the mini-series chooses to centre the case around are the psychic Robert Lees, the actor Richard Mansfield and the Royal physician Sir William Gull (aided by the coachman John Netley). It is worth nothing that the persons who were questioned and regarded as likely suspects by the police of the day – and the figure that Abberline was fairly sure was The Ripper, the Polish immigrant Seweryn Klosowski/George Chapman – are not even depicted or mentioned. The figure nicknamed Leather Apron who was hounded by George Lusk’s Whitechapel Vigilance Committee and Prince Albert Victor who has been floated as a suspect well after the era do get a brief mention (where the mini-series at least shows it has done its research in demonstrating that Prince Albert was not in London at the time of the killings).

What should first be noted about all of these named suspects – Lees, Gull, Mansfield and Netley – is that none of them were ever suspected during the actual investigation by Scotland Yard back in 1888. American actor Richard Mansfield was appearing in a stage version of The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886) at the time but his sole connection to the case was one attendee being so frightened by Mansfield’s portrayal of Mr Hyde that he wrote a letter to the newspapers saying he was certain that this must mean that Mansfield was the Ripper. There is zero record that Mansfield was ever investigated by Scotland Yard, let alone hounded by Abberline as the mini-series depicts. (The stage production of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde we see here even rather absurdly has Armand Assante’s Mansfield undergoing air-bladder makeup transformations that cause his face to bloat and pop after taking the potion when in fact the real Mansfield only achieved what he did through the use of stage makeup).

Similarly, Robert James Lees was never considered a suspect by the police. Lees was a popular spiritualist and medium of the era who had written several books. Much of what is said about Lees can be put down to his own self-aggrandisement – his widespread claim that he was the personal psychic of Queen Victoria and helped her talk to her late husband Albert has never been substantiated beyond his own statements. Lees did write letters offering to help Scotland Yard locate the Ripper and afterwards made grand claims that he had had visions of each of the murders and had led the police to the Ripper but none of this has ever been corroborated beyond Lees’ own statements.

Sir William Gull was, as the mini-series depicts, physician to Queen Victoria and one of the top doctors in London of the day. (In an interesting piece of trivia, aside from being considered a Ripper suspect, William Gull’s fame today is as the person who coined the medical term ‘anorexia nervosa’). Gull was never introduced as a suspect in the case until 1970 and in particular by the book Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution (1976) by Stephen Knight. In the book, Knight built out an elaborate theory that there was a conspiracy among members of the Freemasons, who held influential positions of power in the day, to murder the prostitutes that Prince Albert Victor had dallied with in order to cover up the fact that Albert had married one of them in secrecy. According to Knight’s theory, the women were killed under the guidance of Sir William Gull with the help of coachman John Netley and several high-ups who were all members of the Freemasons. There are a great many problems with Knight’s theory, ingenious and all as it is, the most notable being that much of the so-called proof is based on a good deal of hearsay from people who were dead and the rest patched together with a vast amount of speculation. Subsequent evidence has punctured the theory. The Freemasons have come forward with membership records that show that most of the people in Knight’s supposed conspiracy of Freemasons were not on their membership rolls. Perhaps the most difficult problem with floating William Gull as a suspect is that Gull was 72 years old at the time of the killings and had retired from practice in 1887 after suffering a stroke that had left him partially paralysed and unable to speak. The mini-series has eliminated the Royal Freeman angle and has Gull (perfectly in command of his faculties) engaged in an experiment in madness that makes little sense when explained.

In terms of Jack the Ripper‘s claims to be representing the truth of what happened and revealing the true identity of the Ripper, all that we have is a story that makes a beeline for sensational aspects – psychics, connections to Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Royal Freemason Theories. In writing in one suspect (Mansfield) who played Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and was tied solely to the case by an audience member’s overactive imagination; another who made self-aggrandising claims about aiding the police and was never considered a suspect; and another that is tied solely through a discredited theory that was published ninety years after the fact (and where the theory that ties him there has subsequently been thrown out the window anyway), the mini-series should more properly be considered fiction than historical depiction. The reality that never seems to occur to David Wickes is that Jack the Ripper was a serial killer. Admittedly the fascination with serial killers and forensic psychology was not so prominently in the public eye back in 1988 and so Wickes is only left stretching at some vague generalised notion of ‘madness’ as an explanation. However, the forensics that do date from the era and the behaviour we know about is all consistent with serial killer pathology – to spin this out into vast conspiracy theories is to needlessly complicate the obvious.

The disappointment of the end revelation [PLOT SPOILERS] of Sir William Gull as The Ripper is frustrating. With the Royal Freemason Conspiracy Theory thrown out by David Wickes’s script, there is no real explanation of why Gull was inspired to get into a coach and go and kill prostitutes. There is some talk of him conducting an experiment in madness by ‘splitting the mind’, but this seems to have more in common with Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde than it does with any credible psychological explanation. The script is exceedingly vague about how Gull ever achieved his split of the mind or indeed what such a term means in psychological actuality. In that David Wickes stages Dr Jekyll in the film and later made his own tv version with Jekyll (1990), also starring Michael Caine, you wonder if he has somehow gotten the fact and fiction of the era mixed up.

Certainly, the mini-series has done a commendable job in putting together some reasonably lush sets and costumes. If its consideration of suspects has one tearing their hair out, the mini-series works reasonably well as a murder mystery (so long as you consider it a work of fiction). You keep wanting to watch to see who it finally identifies as its killer. Michael Caine is on fine form as Inspector Abberline, giving a performance that seems to almost entirely be bawled out until he is red in the face. Moreover, Caine is nearer in age to and more closely resembles the real Inspector Abberline than Johnny Depp ever did. Lewis Collins, a few years earlier one of the bad boy pin-ups of British television in The Professionals (1977-83), looks uncomfortable in suit, hat and mustache, his natural ruggedness seeming constrained by being required to be Caine’s sidekick. The most ridiculous performance is the one given by Ken Bones as Robert Lees where Bones plays the part with a ludicrously overwrought nervous intensity. The lovely Jane Seymour has been brought in in a superfluous role solely to give the mini-series another marquee name in the US and a dash of romance with Michael Caine (conveniently writing out the fact that Abberline was married in real-life) but she ends up being given far too little to do.

David Wickes was a regular director in British television since the 1970s and had worked on many of the action series of the day, including The Professionals, The Sweeney (1975-8) and had directed The Sweeney (1977), the first film spinoff of the latter. The only other theatrical film Wickes made was the motorcycle racing drama Silver Dream Racer (1980). Wickes had earlier directed Jack the Ripper (1973), a part-documentary, part-dramatised mini-series that examined the case. Subsequent to the success of this mini-series, Wickes made two other adaptations of classic Victorian-era horror stories with Jekyll (1990), a tv movie also starring Michael Caine in the title role(s), and Frankenstein (1992), a tv movie with Patrick Bergin as the doctor and Randy Quaid as the creature.

The other Jack the Ripper films include:- those that conduct supposedly straight tellings of the details of the case such as Jack the Ripper (1959), the Spanish Jack the Ripper of London (1971) with Paul Naschy, Jess Franco’s Jack the Ripper (1976) with Klaus Kinski, The Ripper (1997), the Alan Moore graphic novel adaptation From Hell (2001) with Johnny Depp, the German Jack the Ripper (2016), and Ripper Untold (2021) and its sequel Ripper’s Revenge (2023). There are a number of other works that feature The Ripper as a central character like Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927), and its remakes The Lodger (1932), The Lodger (1944) and Man in the Attic (1953), as well as Room to Let (1950), although most of these vary widely from the known details. More prevalent have been speculative treatments, including the likes of:- having the contemporary but fictional figure of Sherlock Holmes solve the mystery in A Study in Terror (1965), Murder By Decree (1979) and Holmes & Watson: Madrid Days (2012); the Ripper being an alien spirit that possesses Scotty in Star Trek‘s Wolf in the Fold (1966) and with similar stories occurring in episodes of Kolchak: The Night Stalker (1974-5) and The Outer Limits (1995-2002); the Ripper being Dr Jekyll in both Dr Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971) and Edge of Sanity (1989); Jack the Ripper’s daughter featuring in Hands of the Ripper (1971); H.G. Wells and the Ripper travelling through time to the present day in Time After Time (1979) and its tv series remake Time After Time (2017), as well as a time-travelling Ripper appearing in episodes of tv series like Fantasy Island (1977-84), Goodnight Sweetheart (1993-9) and Timecop (1997-8); The Ripper having travelled out West in the Knife in the Darkness (1968) episode of the Western tv series Cimarron Strip (1967-8) and the film From Hell to the Wild West (2017);The Ripper being resurrected or copycated in the present day in The Ripper (1985), Bridge Across Time/Terror at London Bridge (1985), Jack’s Back (1988), Ripper: Letter from Hell (2001), Bad Karma (2002), The Legend of Bloody Jack (2007), The Lodger (2009) and Whitechapel (tv mini-series, 2009); a parody segment of Amazon Women on the Moon (1987) that speculates that the Ripper was in fact the Loch Ness Monster; the Babylon 5 episode Comes the Inquisitor (1995) that reveals the Ripper was taken up by aliens and redeemed; transposed to Gotham City in the animated Batman: Gotham By Gaslight (2018); even turning up as a character in the French animated film Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart (2013). Also of interest is the tv series Ripper Street (2012-6), a detective series set in London in the immediate aftermath of the Ripper killings.