Japan. 1988.

Crew

Director/Based on the Comic Created by Katsuhiro Otomo, Screenplay – Izo Hashimoto & Katsuhiro Otomo, Producers – Shunzo Kato & Ryohei Suzuki, Photography – Katsuji Misawa, Music – Susumu Miyodangawa & Shoji Yamashiro, Animation Supervisor – Atsuko Fukushima, Art Direction – Toshiharu Mizutani. Production Company – Akira Committee.

Plot

2019 in Neo-Tokyo. Following a police arrest, the street punk Tetsuo is taken prisoner by the top-secret Akira Project where he is subjected to a series of tests designed to unleash his latent psychokinetic powers. However, Tetsuo becomes more powerful than anyone has imagined and breaks out, creating a swathe of psychic destruction across the city as he mutates into another lifeform.

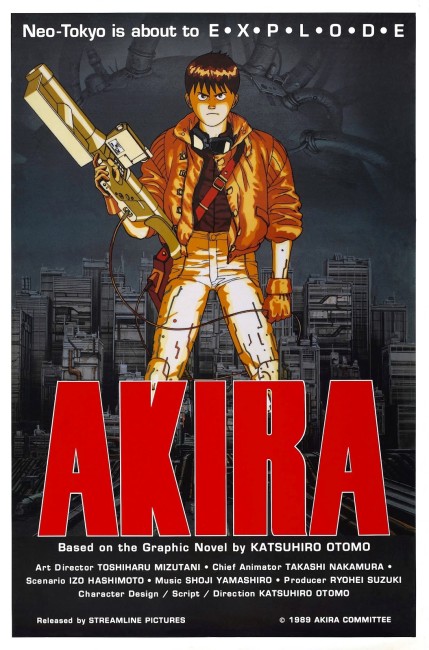

Animation (anime) and comic-books (manga) are a major industry in Japan. These can prove a source of endless fascination for Western audience with their often amazingly high levels of sublimated violence and sexuality. Akira, itself the adaptation of a telephone-book sized weekly manga, quickly became Japan’s most acclaimed anime film.

Upon its international release in 1989, Akira single-handedly brought anime to attention in the West and transformed it into a cult phenomenon. Within a matter of years, there were several English-language magazines devoted exclusively to anime, while anime releases have gained their own separate niches in most videostores, even specialty stores devoted to anime/manga in some Western cities. As a result of Akira, writer/director/creator Katsuhiro Otomo became one of the few recognisable anime names in the West.

Katsuhiro Otomo began as a graphic artist and has been drawing and writing manga since the 1970s. The Akira manga, which was published between 1982 and 1990 after first appearing in Young magazine, was extraordinarily ambitious in scale – when Marvel brought up the English-language rights they released it in 38 serialised volumes. Otomo had also worked on film prior to this, designing characters for animated films like Crusher Joe (1983) and Rintaro’s Harmageddon (1983) and directing segments of the anime anthologies Neo-Toyko (1987) and Robot Carnival (1987).

Since Akira, and despite the enormous acclaim he received as a result, Katsuhiro Otomo’s output has been erratic – up until the mid-00s, he only directed one-and-a-half other films, the live-action World Apartment Horror (1991) and an episode of the anime anthology Memories (1995). However, the attachment of Katsuhiro Otomo’s name to a project even in the vaguest regard – Roujin Z (1991), Perfect Blue (1997), Spriggan (1998), Metropolis (2001) – became enough to carry many films further than they might have otherwise have gone.

Otomo promised a feature-length return to anime but a number of projects, including the intriguing idea of a collaboration with Alejandro Jodorowsky, were announced but never emerged. It took Otomo sixteen years to finally do so with the impressive Steampunk anime Steamboy (2004), which he followed with the live-action Bugmaster (2006) about a wandering exorcist and the Combustible episode of the anime anthology Short Peace (2013).

On screen, Akira plays like a collision between Cyberpunk and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). It is a stunning vision – one that fuses Cyberpunk urban nihilism, religious chiliasm, what seems like a transcendent vision of The Bomb and a wild punk version of The Fury (1978) all into one (if not entirely coherently). Mostly, Akira is constructed in a series of climaxes that get progressively bigger and bigger until they almost reach a point of sensory overload. It is a film of epic, even cosmic, scope – Tetsuo’s path of destruction through the city, wiping out bridges, tanks and vast cryonic vats, silently journeying up into space to tear apart a Star Wars laser satellite and melding with the Akira entity as a ball of pure white light consuming the entire city in its path, is exhilaratring and awe-inspiring. The final vision travelling through space, following beams of light, which finally coalesce into a giant eye that whispers “I am Tetsuo” before the end credits roll quite blows the mind with its scale of wholly cosmic grandeur.

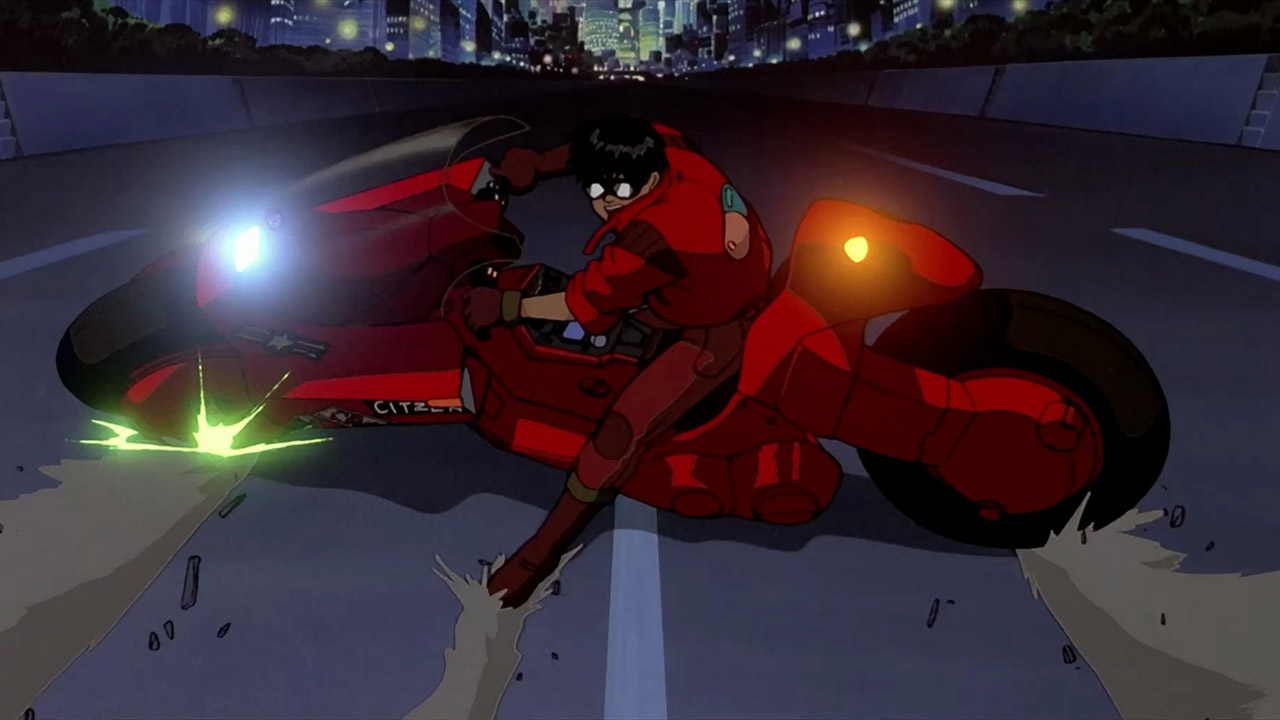

Neo-Tokyo is a vista of grimy downbeat Cyberpunk imagery filled with bewilderingly beautiful neon cityscapes, holographic ads and thousand-storey buildings. This aspect of the film is disappointing in some respects – the background is rarely of much relevance and the vehicles and particularly the fashions never seem to have changed in 31 years. The action scenes pelting down tunnels on bikes and hoverjets in a bedlam of lights and sound however are breathlessly exciting.

The film also has an amazingly high level of violence, the casual gratuitousness of which proved somewhat amusing to the Western theatrical audience I was sitting amongst as they watched about the dozenth person get their teeth kicked in. Much of the film plays as wish fulfillment on political anarchy and destructive power fantasies – its subtext is not a particularly profound one. However, as an exercise in escalating size and sense of wonder, Akira cannot be equalled.

For several years, since 2003, there have been plans for a US-made live-action remake of Akira, currently announced for sometime in the 2020s. The motorcycles later made a cameo appearance in Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One (2018).

Trailer here

Better quality Japanese trailer here (no English):-