USA. 1932.

Crew

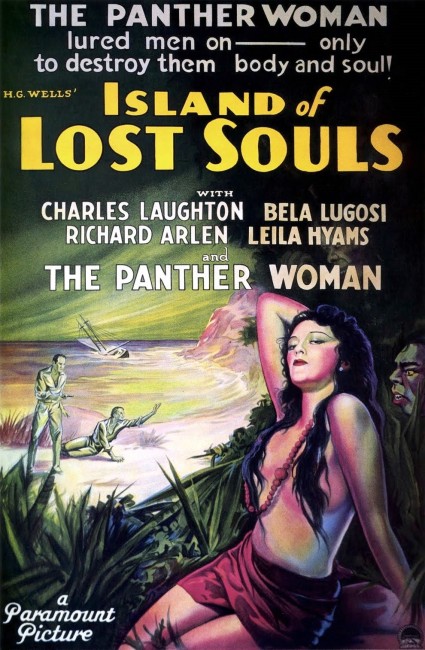

Director – Erle C. Kenton, Screenplay – Philip Wylie & Waldemar Young, Based on the Novel The Island of Dr Moreau by H.G. Wells, Photography (b&w) – Karl Struss, Special Effects – Gordon Jennings, Makeup – Wally Westmore, Art Direction – Hans Dreier. Production Company – Paramount.

Cast

Charles Laughton (Dr Moreau), Richard Arlen (Edward Parker), Kathleen Burke (Lota), Arthur Hohl (Dr Montgomery), Leila Hyams (Ruth Thomas), Paul Hurst (Captain Donahue), Bela Lugosi (The Sayer of the Law), Stanley Fields (Captain Davies), Tetsu Komai (M’Ling), Hans Steinke (Ouran)

Plot

Edward Parker is picked up by the freighter Covena after being shipwrecked at sea. Following a fight with the captain, he is dumped aboard the launch of Dr Moreau. Moreau welcomes Parker to his island. Parker soon discovers that Dr Moreau is conducting vivisection experiments in order to turn animals into human beings. He finds that Lota, the native girl that Moreau is trying to push him toward, is a transformed panther and that Moreau wants to keep him there to conduct an experiment in mating her with a human.

The Island of Lost Souls was the first of three screen adaptations of H.G. Wells’s novel The Island of Dr Moreau (1896). It has since been remade twice – as the dull The Island of Dr Moreau (1977) featuring Michael York as the castaway and Burt Lancaster as Dr Moreau, and the underrated The Island of Dr Moreau (1996) featuring David Thewlis as the castaway and Marlon Brando as the good doctor. There have also been several uncredited adaptations – The Island of Terror (1913), the Filipino-shot films Terror is a Man (1959) and The Twilight People (1972), and the cheap Dr Moreau’s House of Pain (2004).

The Island of Lost Souls was one of only a handful of adaptations of his work that H.G. Wells saw within his lifetime and he was reportedly not happy with the results. The film adds many elements to the story, notably the characters of Dr Moreau’s burned-out assistant Montgomery and the Panther Girl, the woman that Moreau tries to get the hero to mate with, he unaware that she is a beast person too. (Both of these characters have been retained by subsequent film adaptations). The hero also gets a fiancee who turns up on the island in the latter half of the film.

Most of the rest of the film is faithful to the H.G. Wells story, thanks to a literate script by Philip Wylie, the science-fiction author who also co-wrote the book that became When Worlds Collide (1951), as well as the film adaptation of H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man (1933). Certainly, The Island of Lost Souls is far more faithful to the source text than the adaptations of Frankenstein (1931) and Dracula (1931) that had been conducted by Universal the preceding year were to their respective original books.

However, you can see what it is that had H.G. Wells upset – he wrote The Island of Dr Moreau as a Frankensteinian take on the Garden of Eden myth, one where the creations take revenge on their flawed creator. While The Island of Lost Souls does not change this in any way, what it does is to play it as a horror film, one that contains a startlingly lascivious undertow and a number of sexually taboo overtones. H.G. Wells’s considerations aside, this is an approach that makes The Island of Lost Souls work the best of all the story’s screen adaptations so far.

The Island of Lost Souls is well directed by Erle C. Kenton, not known as a director of subtlety. The rest of Erle C. Kenton’s work is a nondescript series of B crime melodramas – his two other genre works were the passably routine Universal monster bashes House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945). Kenton however does a fine job here, being especially good at making the studio sets look like a suitably heated tropical island. The makeups on the Beast Men are only so-so – The Beast Men rarely have distinctive personalities they way they do in the other versions, they are just an aggregate body of animal creatures that Kenton effectively keeps sinisterly lurking in the shadows.

There is also an undeniable sexual element to the film. Kathleen Burke gives a performance that balances between naive innocence, exoticism and sultry sensuality. There is a fine, subtle scene where she and Richard Arlen meet beside a pool, partially shot reflected in the water, with she coming onto him and then revealing her claws, before he suddenly realises she is one of Dr Moreau’s animals too. There are directly sexual references with Moreau noting that he wants to mate her with a human just to see what happens. For an era that refused to even show a married couple inhabiting the same bed, the suggestions of bestiality are startling – no wonder the film was banned in the UK until the 1960s.

There is also much that was forced on the film due to the time it was made, which has undeniable effect – there is no musical score for example (a result of the film being made in the early few years of the sound era). Furthermore, both the book and this film were written before the discovery of DNA – thus Dr Moreau is a vivisectionist creating his hybrids through surgery, as opposed to both remakes where he is cleaned up and made into a genetic engineer. The idea of him being a surgeon, creating hybrids through brute force, is something that gives the lab scenes a much nastier edge. As a result, the ending where the creations turn and vivisect Moreau has an incredible shock sting to it that neither remake managed.

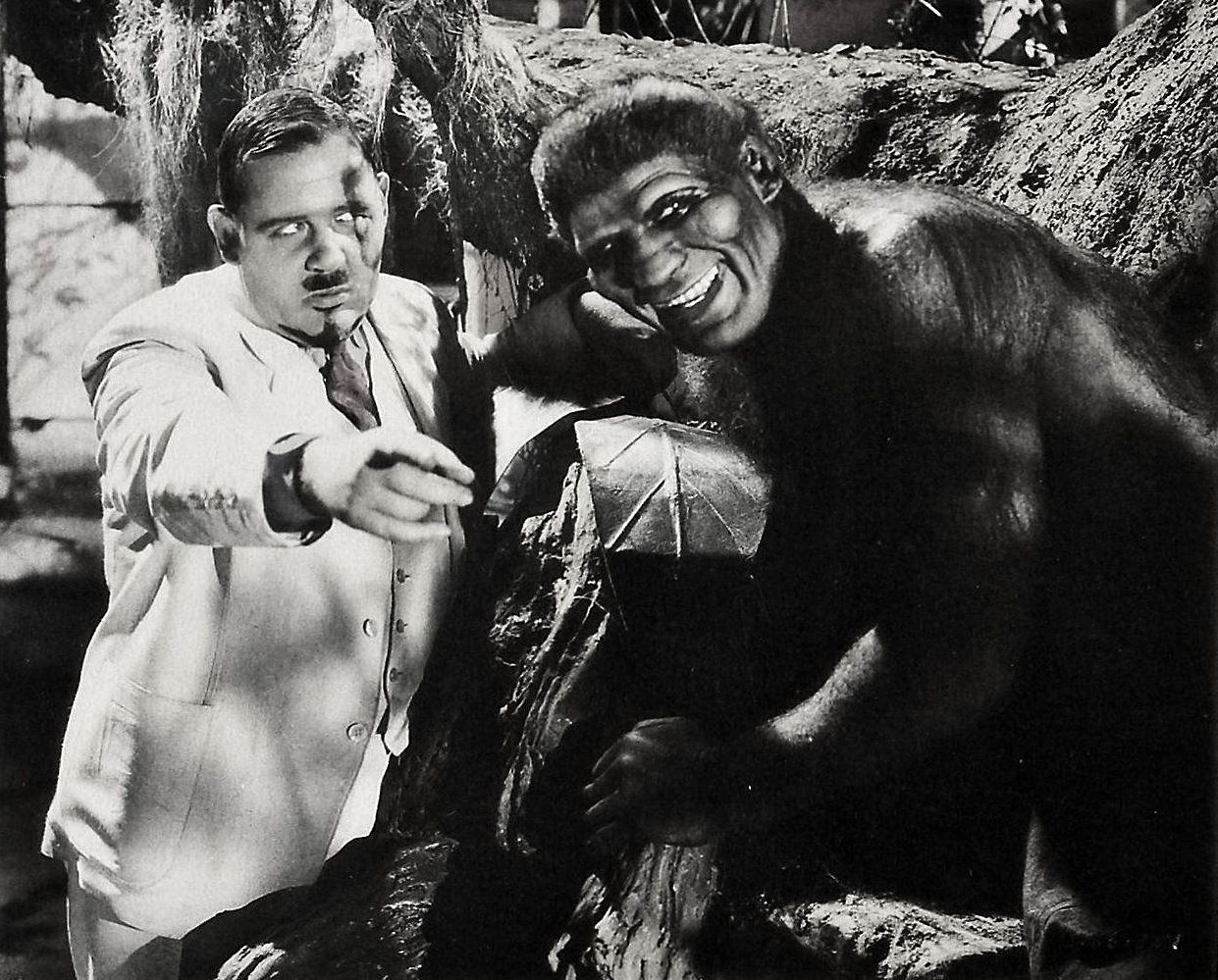

The Dr Moreau role is played by Charles Laughton. Laughton was a classic actor who played great character roles like Nero in The Sign of the Cross (1932), Henry VIII in The Private Life of Henry VII (1933), Captain Bligh in Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), the title roles in Rembrandt (1936) and I, Claudius (1937) and was the definitive Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939). He also directed the excellent psycho-thriller The Night of the Hunter (1955). Laughton gives a great performance – in tubby build with Mephistophelean beard, he is alternately arrogant and assured at the same time as he is fascinatingly charismatic. If you compare Charles Laughton’s performance to Colin Clive in the 1931 Frankenstein, there seems a world of difference – where Clive’s mad scientist seemed craven and the film pitched at a level of overwrought melodrama, Laughton’s Dr Moreau and the film seem realistic and without melodrama.

In fact, with Charles Laughton’s performance and the torrid tropical setting, the film takes on undeniable colonial slave owner overtones – outfitted in pith helmet and wielding a whip against the Beast Men, Laughton seems more akin to one of the white plantation owner in the likes of Mandingo (1975) and Drum (1976) than to Colin Clive’s Frankenstein. In this sense, The Island of Lost Souls taps into many themes that ran through 1930s/40s horror/sf cinema. Most overtly, there is the fear, begun with Frankenstein, that science was defying divine provenance and opening up a Pandora’s Box that would unleash socially devastating forces.

More important is the preoccupation with the borderlines of civilisation. Serials of the era perpetually colonised Africa, Asia, the Old West, underground and outer space as realms of exotic adventure. There was a sense that there were definite parameters beyond which civilisation no longer applied. This was the era of The Depression where a substantial part of the population had become disenfranchised and been rendered dissolute. The films of the era often held wish fulfilment fantasies with the likes of Tarzan the Ape Man (1932) and Lost Horizon (1937) about people abandoning civilisation and finding an alternate paradise in undiscovered worlds in respectively Africa and Asia. Perhaps the most famous variant on the theme was King Kong (1933), which was about the discovery of a great beast that ruled a primal jungle realm who is tragically conquered and brought down by civilisation.

Both King Kong and The Island of Lost Souls tap into sexual themes. For both films, the island beyond the borderlines of civilisation harbours animal primitivism, which in both cases is equated with sexuality. Kong represents rampaging desire for a blonde girl. There is a similar scene here of the animal sexuality threatening civilised people with its unruly passions – of the Panther Girl trying to tempt the hero to mate with her. Upon the blonde fiancee’s arrival on the island, a Beast Man peers in the window at her as she goes to go to bed and then tries to break into the room. The Beast creatures here clearly represent raw, primal sexuality untamed by civilisation, while Leila Hyams is held up as a paragon of unattainable desirability.

The film naturally climaxes with the island and the creations of super science burning in flames, the forces of bestial sexuality destroyed and the hero and heroine in each other’s arms – in other words, the status quo of civilised reason and tamed passions having been restored.

Director Erle C. Kenton (1896-1980) later went on to make several of Universal’s horror sequels with The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), House of Frankenstein (1944) and House of Dracula (1945), as well as the Old Dark House thriller The Cat Creeps (1946).

Trailer here