USA. 2019.

Crew

Director – Xavier Burgin, Screenplay/Producers – Ashlee Blackwell & Danielle Burrows, Based on the Book Horror Noire: Blacks in Horror Films from the 1890s to the Present by Robin R. Means Coleman, PhD, Photography – Mario R. Rodriguez, Music – Timothy Day. Production Company – Stage 3 Productions.

With

Meosha Bean, Ashlee Blackwell, Robin R. Means Coleman, PhD, William Crain, Rusty Cundieff, Keith David, Loretta Devine, Ernest Dickerson, Tananarive Due, Ken Foree, Mark H. Harris, Richard Lawson, Tina Mabry, Kelly Jo Minter, Miguel A. Nuñez Jr., Paula Jai Parker, Jordan Peele, Ken Sagoes, Monica Suriyage, Tony Todd, Rachel True

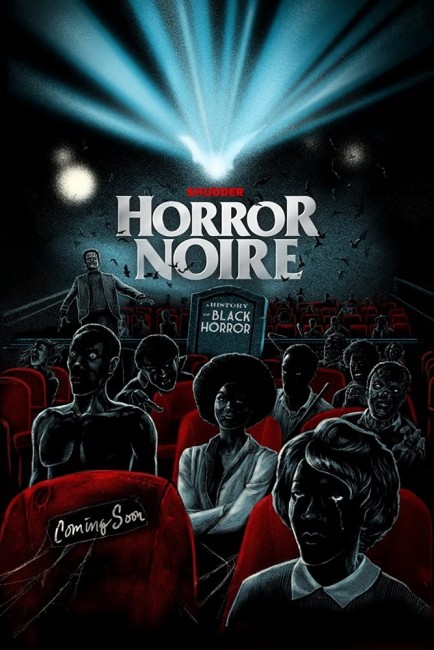

Horror Noire is a documentary that was made for the celebration of US Black History Month. It details representation of African-American characters and the participation of African-American creative talents in horror cinema. It is based on the book Horror Noire: Blacks in Horror Films from the 1890s to the Present (2011) by Robin R. Means Coleman, a professor at Northwestern university in Evanston, Illinois, who has lectured on the topic. The film should not be confused with Horror Noire (2021), a subsequent horror anthology featuring contributions from African-American directors, which is unrelated to this beyond the similarity of titles.

When it comes to critical writing, I think there are two types of criticism. I make a divide between criticism that is aligned to a set of objective standards (even if the standards are self-imposed critical rules) and what you can call very subjective criticism. Objective criticism will founder around questions like the story, the direction, performances etc. Here a critic judges a work against a yardstick of how it compares in terms of these values. These criticisms are usually made in terms of comparisons to other works.

What I call subjective criticism comes when certain aspects of a film are focused on or seen as more important dependent on who the film speaks to or the individual relevancy of the subject matter. Everyone has had the experience of watching a particular film or tv show that might mention or be shot in their home town or country – this is something that gives it a particular level of fascination to the individual that the average viewer would not get. Similarly, one’s political, gender and racial identification make a work of more interest if it features or delves into this area. This is something that might be invisible to an average viewer who does not come from or belong to one of those groups. In many of these instances, a work will be critically evaluated and praised not because of story, production values etc but the extent by which it offers positive (or negative) portrayals of those who belong to the group

Horror Noire becomes highly interesting to me because it focuses on a very subjective area of interest – African-Americans in horror cinema. It is one where I as a white non-American clearly don’t belong to the tribe. The film offers a glimpse of issues and criticisms pertinent to its people, while works are praised or criticised for reasons that may have escaped me when I originally viewed them due to my lack of immersion in the culture.

The film begins in the silent era with discussion of the notorious The Birth of a Nation (1915). Various of the interviewees speak about the bad cliché roles of the 1930s and 40s with occasional mention of the works of Spencer Williams, the first Black director. The Black hero is seen to have begun with Duane Jones in Night of the Living Dead (1968) who is called “the first Black man in charge of his own destiny” [presumably on screen]. The film then moves into discussion of Blaxploitation Cinema where there is some debate whether it was good period for African-Americans or whether the genre fell into clichés of what white people thought African-American culture was. Everyone speaks in admiration of the late William Marshall, the star of Blacula (1972), while the film’s director, a septuagenarian William Crain, talks of being the only Black face on the film’s set behind the camera. Some of the other classics of the cycle such as Ganja and Hess (1973) and Sugar Hill (1974) are praised.

As we move into the 1980s, the interviewees discuss the trope of Black Dies First in the Slasher Film (although this is disputed by Robin Means Coleman), along with other cliché caricatures like The Magical Negro, The Sacrificial Negro and the Badass Black with the citing of several genre examples. The Shining (1980) is criticised for the unnecessary death of Scatman Crothers, especially in contrast to his survival in the book.

Assorted praise is given for films of the 1990s and beyond such as The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988), Def by Temptation (1990), Candyman (1992), Tales from the Crypt Presents Demon Knight (1995), Tales from the Hood (1995), Eve’s Bayou (1997) and AVP: Alien vs Predator (2004), as well as the phenomenon of hip-hop horror in the early 2000s. Attack the Block (2011) and The Girl With All the Gifts (2016) are the only two non-American films mentioned.

In the final section, the film arrives at the increasing rise of African-American filmmakers with interviews with earlier Black directors like Ernest Dickerson and Rusty Cundieff, as well as Jordan Peele discussing the success of his crossover hit Get Out (2017). The film was made just before the massive change in casting and hiring practices that began in the late 2010s, which saw far greater numbers of African-American participating in and making films.

While I enjoyed Horror Noire, I do have to take issue with some of Robin Means Coleman’s interpretations. The film begins its discussion with The Birth of a Nation. I have difficulty listing The Birth of a Nation under the definitions of what constitutes a horror film that I use on this site. This does represent the very different cultural perspectives – Robin Means Coleman is an African-American woman, I am a white guy and non-American. To me, The Birth of a Nation reads as a work of creative historical revisionism and political propaganda. However, to Coleman what stands out is the treatment of the African-American character and the demonisation of African-American men as lust-crazed and obsessed with white women for which he is duly hunted down. This as an aspect that constitutes a work of horror in her definition. To me, horror is a work that employs a certain series of themes, tropes and stylistic directorial devices and I cannot say that The Birth of Nation works as horror in this regard (by my definitions). This trope of the lust-filled Black man obsessed with a white woman however seems to be one that has struck a chord in horror subsequently. A number of examples are pointed to, including Candyman (1992).

I would also quibble with the comment that Coleman makes a couple of times throughout where Kong in King Kong (1933) is regarded as a symbol of a Black man. Kong is a giant ape and there is nowhere throughout the film where it is specifically identified with one human racial ethnicity – at most, he is worshipped by a tribe of South Seas natives that were cast with Black actors. This is where the Horror Noire starts to get into the same kind of specious territory as the interviewees in Room 237: Being an Inquiry Into The Shining in 9 Parts (2012) and starts seeing symbols and intentions that come more out of the particular viewer’s imagination than were ever intended on the part of the filmmakers. At most you can “this is one possible way to interpret things” but to say conclusively Kong is a Black Man is to draw a connection that is not supported by anything other than speculative interpretation. (If someone can point me to any source that makes the connection direct such as a quote from Merian C. Cooper or Ernest B. Schoedsak, I will be happy to admit I am wrong here).

In a similar piece of dubious symbolic interpretation, there is the claim that the bug eyes and large lips of the creatures in 1950s monster movies like The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), The Mole People (1956) and The Fly (1958) are intended as symbols of white man’s fear of African-Americans. In all honesty, this is not symbolism I see or one that you can clearly say was intended by the filmmakers – it seems more the particular viewer latching onto an interpretation to bolster their own thesis.

This speculative symbolism also seems to be at play when the academics start citing films like Blackenstein (1973) and Dr Black and Mr Hyde (1976) as reflective of the Tuskegee Experiments (which were conducted by the US Army between the 1930s and 1970s where Black soldiers were deliberately infected with syphilis). I have seen both films and what they read as being is simply Blaxploitation attempts to copy monster/mad scientist movies of the 1930s/40s. The reading of experiments conducted by the US Army into them – especially when Blackenstein is a film being made by white creative talent – seems more a projection of the academic than anything that was intended by the filmmaker.

Trailer here

Full film available here