Crew

Director/Screenplay – Stephen Sommers, Story – Stephen Sommers, Lloyd Fonvielle & Kevin Jarre, Producer – Sean Daniel & James Jacks, Photography – Adrian Biddle, Music – Jerry Goldsmith, Visual Effects Supervisor – John Andrew Berton Jr, Visual Effects – Industrial Light and Magic, Additional Visual Effects – Cinesite & Pacific Mirage Title, Thebes and Hamunaptra Sequence Supervisor – Scott Farrar, Special Effects Supervisor – Chris Corbould, Production Design – Allan Cameron. Production Company – Alphaville.

Cast

Brendan Fraser (Rick O’Connell), Rachel Weisz (Evelyn Carnahan), John Hannah (Jonathan Carnahan), Arnold Vosloo (Imhotep), Kevin J. O’Connor (Beni), Omid Djalili (The Warden), Jonathan Hyde (The Egyptologist), Erick Avari (The Curator), Stephen Dunham (Henderson), Corey Johnson (Daniels), Tuc Watkins (Burns), Oded Fehr (Ardeth Bey), Bernard Fox (Winston Havelock), Patricia Velazquez (Anck-su-namun)

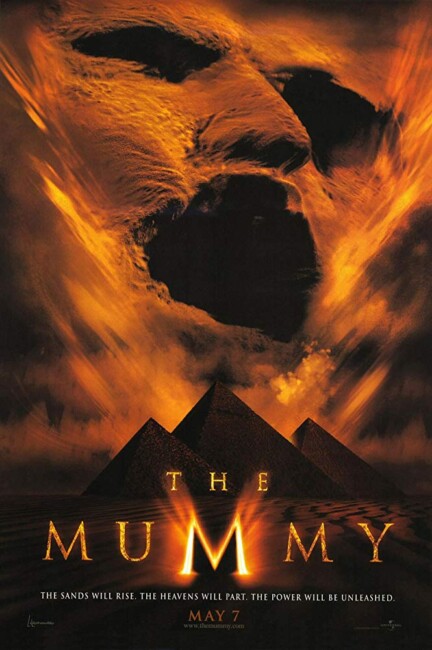

Plot

In 1290 B.C., the Egyptian high priest Imhotep is sentenced to a death too horrible to be described for daring to seduce the Pharaoh’s mistress Anck-su-namun. In 1926, the brother of Evelyn Carnahan, a librarian at the Cairo Museum of Antiquities, obtains a map leading to Hamunaptra, the forbidden Ancient Egyptian city of the dead, from adventurer Rick O’Connell. Evelyn rescues Rick as he is about to go the hangman’s noose in return for his promise to lead them to Hamunaptra. They mount an expedition but find themselves in a race against a rival American expedition. The attempts of both parties to be the first to discover the lost city end up reviving the mummified Imhotep. Imhotep unleashes the twelve Biblical plagues as he attempts to claim the human organs of his desecrators, something that will allow him to regenerate his flesh. He also seeks to incarnate his beloved Anck-su-namun in the body of Evelyn.

The mummy film is maybe one subgenre more than any other that is condemned to B programmer status simply by its theme. The Boris Karloff The Mummy (1932) was a genre classic that, although it came too much in the shadow of the Bela Lugosi Dracula (1931), was given enormous eerie atmosphere by director Karl Freund. The subsequent sequels produced by Universal – The Mummy’s Hand (1940), The Mummy’s Tomb (1942), The Mummy’s Ghost (1944) and The Mummy’s Curse (1944) – soon turned the title character into a clumsy bandaged-wrapped zombie wholly lacking in threat, before the series reached the ignoble nadir of Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy (1955). England’s Hammer Studios conducted a remake of The Mummy (1959), along with a package of other classic Universal horror films. There the character was effectively fed through the polarisation of Victorian morality versus animal passion that the early Hammer films dynamically personified. Alas, subsequent Hammer mummy films – The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb (1964) and The Mummy’s Shroud (1967), with the arguable exception of Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb (1971) – failed to escape the B programmer curse. Outside the English-speaking world, the mummy’s career path was well and truly on a long downward spiral, most notably being pitted in the ring in Mexico’s The Wrestling Women vs. the Aztec Mummy (1964) and against El Santo in Santo and the Vengeance of the Mummy (1971), while Europe offered gore-drenched efforts like Vengeance of the Mummy (1972) and Dawn of the Mummy (1981).

It can be said that the most effective mummy films are those that escape B programmer status by virtue of subsuming themselves into some other genre. The only other halfway effective mummy film has been the underrated The Awakening (1980), which dropped all bandaged-wrapped terrors and created an often subtle story about possession, while modelling itself on the supernatural killings set-pieces of The Omen (1976). (It was also the first mummy film in fifty years to shoot on location in Egypt). This new version of The Mummy was one of several interesting attempts that came out around the same time attempting to revisit the mummy theme using modern special effects technology. Others included the fascinating The Eternal/Trance (1998) and the similarly effects-driven Talos the Mummy/Tale of the Mummy (1998).

This is a nominal remake of The Mummy – although it has only the title and the central character’s name in common with the Boris Karloff original. It abandons most connections to the mummy B movie and happily conflates the genre into a high adventure film a la the Indiana Jones series. If the 1932 version of The Mummy was born out of the emergent romantic horror film created by Universal’s Dracula and the 1959 Mummy was pitted in the British fight with morality and society over animal instinct, then the 1999 Mummy is born out of the modern action-adventure spectacle and the CGI creature movie post-Jurassic Park (1993).

The Mummy 1999 quickly casts off any connection with the shuffling bandage-enwrapped creatures of yore and becomes a much more dynamic figure whose abilities are writ on an epic canvas – it talks and is a black sorcerer who transforms into flurries of sand, blasts locusts and sandstorms out of its mouth, raises armies of the undead and controls hordes of animated scarab beetles, while wielding the Biblical Plagues of Egypt (which, in an ironic about-face, have been placed in the service of a great Egyptian force of evil rather than in the service of the Almighty wishing to free a slave race from the Egyptian yolk).

The Mummy remake was an oft-mentioned project throughout most of the 1990s under directors such as Mick Garris and Clive Barker. Indeed, when Anthony Perkins died in 1992, he was in the midst of shooting a subsequently abandoned remake. Stephen Sommers, the director finally settled on for this version, made his debut with the teen comedy Catch Me If You Can (1989) and followed with the acclaimed The Adventures of Huck Finn (1993). Sommers came into his own as a genre director with the underrated live-action remake of The Jungle Book (1994) which, although it bore more in common with Edgar Rice Burroughs than Rudyard Kipling, had a beautiful sense of epic jungle adventure to it. Sommers disappointed with his next film, the laughably silly Alien (1979)-at-sea clone Deep Rising (1998), which led the way to his being a director whose work is almost entirely driven by CGI effects (see below for Sommers’ other films).

Stephen Sommers has a talent for crafting epic adventure. In The Jungle Book, Sommers created an adventure-movie version of India that was more fabulous and more mysterious than the real India could ever hope to be and in The Mummy similarly creates a more-fabulous-and-mysterious-than-the-real-Egypt adventure movie version of Egypt. The film is filled with incredible vistas of sandstorms, lost cities seen both in the fabulousness of their heyday and the splendour of their ruins, treasure chambers and booby-trapped tombs. No sky seems merely blue but boils with coloured clouds and larger-than-life CGI moons. Sommers has an ability to direct satisfyingly kinetic action set-pieces – shootouts with hordes of charging horsebound Bedouins, fights aboard burning ships, adventurers attempting to combat mummies with machine-guns and swords, biplanes racing against giant face-shaped sandstorms and a full-tilt Evil Dead (1982)-styled climatic set-piece up against zombified mummy priests.

For all that, Stephen Sommers’ Mummy crumbles into a lightweight popcorn munch whose taste is immediately forgotten as soon as one leaves the theatre. When one looks at it, The Mummy 1999 stirs no more and no less than the sum of the elements that Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) assembled. Yet Raiders became an instant classic, while The Mummy falls well short of such stature. The difference is more akin to that between Raiders and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) – where, by the time of the third of the Indiana Jones film, the panache and kinetic inventivity of the first film had degenerated into ham-fisted slapstick.

Stephen Sommers’ failing is to play the film for too much common denominator audience-pleasing humour. The two leads make flip quips the whole way through and what few moments of horror there are drowned out by Army of Darkness (1992)-styled gags with skeletons playing football with their heads, Rachel Weisz accidentally knocking down a domino line of library shelves and the like. Stephen Sommers is working with a one-dimensional script and a less-than-serious attitude toward it by he and the principals is something that causes the film’s suspension of disbelief to fold at the knees.

Neither do the leads work. Brendan Fraser comes with too much baggage of casting as an amiable lunkhead in comedies like Encino Man/California Man (1992), Airheads (1994), George of the Jungle (1997), Blast from the Past (1999) and Dudley Do-Right (1999). There is no depth to his character – we, for instance, never learn what he, an American, is doing adventuring in Egypt in the first place. A handsome stalwart leading man type such as a Harrison Ford, a Tom Selleck or even a John Wayne would have carried this part in their sleep but Brendan Fraser’s goofy eye-rollings strip the character of any heroic stature.

Similarly, Rachel Weisz plays the fruity British accent up but gives an awful performance as always and is not believable as a period woman. As the title character, Arnold Vosloo is never required to do more than look sinister, while John Hannah makes for irritating comic relief. The less-than-single-dimensionality of the writing makes the parts seem even slighter. Even more unforgivably, most of the Arabic characters in the film seem written as comic foil racial caricatures where anybody of Arabic persuasion is portrayed as craven, greedy and stupid.

Eventually the film’s persistent spectacle and dynamism carries it to a certain level of likeability, albeit entirely forgettable likeability. You cannot deny that Stephen Sommers directs action well but neither can you deny that the miscast leads and a far too broad audience-pleasing sense of humour deflates The Mummy as a film. Its lack of belief in its own seriousness is the dividing line between a forgettable popcorn film and what could have had the makings of a classic.

Stephen Sommers, Brendan Fraser, Rachel Weisz and most of the supporting cast reunited for a sequel The Mummy Returns (2001), while Brendan Fraser only returned for The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor (2008) under director Rob Cohen. Both of these collapse into arrant silliness under the weight of special effects bombast. There was a further remake The Mummy (2017) starring Tom Cruise. The Scorpion King (2002) was a spinoff from The Mummy Returns and produced four sequels with The Scorpion King: Rise of a Warrior (2008), The Scorpion King 3: Battle for Redemption (2012), The Scorpion King 4: Quest for Power/The Scorpion King: The Lost Throne (2015) and Scorpion King: Book of Souls (2018). There was also an animated tv series The Mummy: The Animated Series (2001-3), which lasted for two seasons and 26 episodes.

Stephen Sommers next went onto revive other famous monsters in the amazingly silly Van Helsing (2004), the live-action adaptation of the toy line with G.I. Joe: The Rise of the Cobra (2009) and the Dean R. Koontz adaptation Odd Thomas (2013). Sommers has also produced all the The Mummy and Scorpion King spinoffs and G.I. Joe: Retaliation (2013).

(Nominee for Best Special Effects, Best Makeup Effects and Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 1999 Awards. No. 7 on the SF, Horror & Fantasy Box-Office Top 10 of 1999 list).

Trailer here