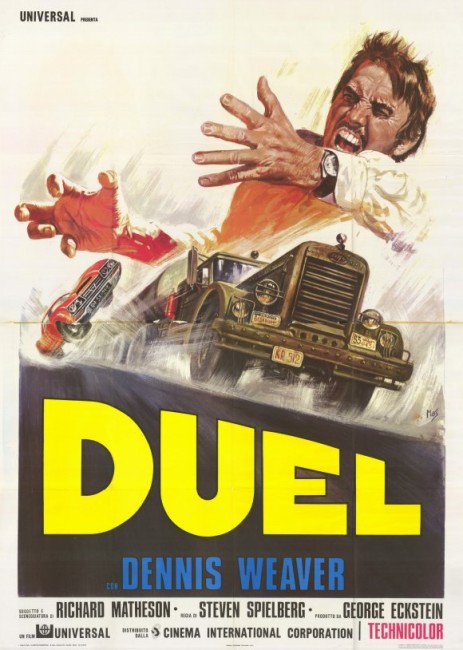

USA. 1971.

Crew

Director – Steven Spielberg, Screenplay/Based on the Short Story by Duel (1971) Richard Matheson, Producer – George Eckstein, Photography – Jack A. Marta, Music – Billy Goldenberg, Art Direction – Robert S. Smith. Production Company – Universal.

Cast

Dennis Weaver (David Mann)

Plot

Salesman David Mann is on his way to a business meeting when he goes to pass a truck on the road. The truck driver takes objection to this and proceeds to block the road whenever Mann tries to pass. The driver then causes Mann to nearly crash into an oncoming car. This escalates into a deadly cat-and-mouse game with the truck relentlessly harassing, playing hide’n’seek with and trying to kill Mann.

This remarkable little film heralded the arrival on the scene of a tenderfoot new director by the name of Steven Spielberg. Steven Spielberg had by his own account gotten a job at Universal in the late 1960s simply by dressing up in a suit, walking in through the gates and taking over an uninhabited office. (Try and imagine someone getting away with that today. Although there have been some voices in recent years disputing the truth of this story). From there, Spielberg managed to get jobs directing episodes of various tv series – The Name of the Game (1968-71), Night Gallery (1969-73), Marcus Welby M.D. (1969-76) and the Columbo tv movies – before going onto make this tv movie. Even back then the Steven Spielberg name was wowing people and the success of Duel on the small-screen proved so great it was expanded slightly and released to cinemas outside of the US in 1972.

Duel was based on a 1971 short story published in Playboy by noted genre novelist and screenwriter Richard Matheson, who also wrote The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), episodes of The Twilight Zone (1959-64) and most of Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe films, among a host of others. (See bottom of the page for Richard Matheson’s other genre titles). Matheson claims the story was inspired by a road rage incident that happened shortly after he heard that John F. Kennedy had been shot.

Before he started rediscovering his childhood and became a household name, Steven Spielberg made some very good and muchly underrated films, which easily stand up with the best of his popular oeuvre. Duel and Jaws (1975) are horror shows. In either film, Steven Spielberg introduces a non-human antagonist that symbolically emerges out of the blue and smashes through the placid lives of his everyman protagonists. In these early films, Spielberg demonstrated a great ability to underscore his flights of fancy with the wittily banal. The opening here is a marvellous picture of normality with its overlaid point-of-view shots as Dennis Weaver leaves Los Angeles, accompanied by snippets of radio talkback voices on the soundtrack banally nattering on about everything from the percussive use of meat to a man concerned about how his being a house-husband bluntens his role as the head of the house. Like every good horror film, this is a picture of normality only waiting for the intrusion of the inexplicable to turn it on its head …

When the assaults of the truck do emerge, Steven Spielberg manages to wind Duel up to a level of tension that becomes almost unbearable. Like the moment when the truck turns around and charges down on Dennis Weaver as he is sheltered in a fragile phone-booth trying to call the police; or where it starts bearing down behind and slamming into Weaver’s car in a 100 mph race; even just the sinister images of the truck waiting on the side of the road or at the end of a tunnel. One scene in a truckstop diner is a masterful evocation of paranoia with Dennis Weaver emerging from the men’s room to find the truck parked outside and then, accompanied by his feeble internal monologue, starts trying to work out the identity of the driver, imagining himself challenging one of the men in the cafe to a fight before in a moment of exquisite black irony the man he believes is the driver departs in a pick-up truck.

The film comes with some often stunning camerawork. Steven Spielberg and Jack A. Marta transform the dust and oil begrimed, pollution-belching shape of the truck into something primal. The truck is first seen in a tire-level camera cruise that travels right down its length at wheel-level and subsequently sits under its slowly churning central axle or racing alongside its vibrating tires. Spielberg and Jack Marta generate such a sense of presence that a wheel waiting across the road, a puffing smoke stack or the baleful omniscience of the truck’s giant grille and headlights filling a rear-vision mirror or a back window are eventually enough to convey the personality of the truck in themselves without seeing the whole of it.

The fact that the driver is never identified is significant. Some cinema reference works have been happy to pigeonhole Duel as a science-fiction film – the fact that the truck’s driver is rarely seen making for an obvious man-vs-machine allegory. This seems to be missing the point. In seeing Duel, it becomes a difficult case to maintain – the driver is clearly seen silhouetted in the cab, his beckoning arm a couple of times, while at the climax the camera joins him in the cab for the first time in two almost subliminal shots, one of him changing gears, the others of his hands holding the wheel. Certainly, the Man vs Machine analogy rears up over the film but it is only a metaphor and Duel reads as a standard psychological thriller in every other way. It is a metaphor Richard Matheson is not unaware of, his deliberate choice of character name makes the film literally about Man(n) vs Machine. By the end, with the truck going over the cliff in slow-motion accompanied by a bestial roar and Dennis Weaver’s eventual reduction to non-verbal grunts as he conducts a dance of triumph, Steven Spielberg and Richard Matheson have symbolically stripped Mann to the point he is caveman fighting a primitive leviathan.

However, the presence of the driver and particularly the scene in the diner where Dennis Weaver is trying to guess the identity of the driver show that Duel is not a science-fiction film – and to call it a science-fiction film is to treat the metaphor in a deadeningly literal way. If anything, Duel has a lineage to Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) and George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) in that it is a film of existential Out of the Blue horrors, films where the respective directors withhold any explanation for the gruelling assaults their protagonists are undergoing and where the very lack of an explanation behind the assault creates a sense of overwhelming anxiety.

Some scenes were added to Duel to bump up the running time for cinematic release, namely the brief scene where Dennis Weaver makes a phone-call to his wife and the sequence where the truck aids a school bus. These scenes do not add a great deal, particularly the school bus one, which takes an unnecessary lightness in contrast to the sinister threat the truck has elsewhere, although this is only a minor quibble in an otherwise superb film.

A number of films owe a debt to Duel. Wrecker (2015) was a blatant, uncredited scene-for-scene remake of Duel. The likes of the tv movie Killdozer (1974) and other films such as The Car (1977), The Hearse (1980), Christine (1983), Wheels of Terror (1990), Road Train (2010) and Super Hybrid (2010) take up the notion of malevolent, frequently possessed, vehicles. Other films such as Roadgames (1981), The Hitcher (1986), Jeepers Creepers (2001), Joy Ride/Road Kill (2001), Hush (2008), Evil Things (2009) and Unhinged (2020) mimic the tense psychological road games. Later, in a move that infuriated Steven Spielberg, an episode of the tv series The Incredible Hulk (1977-81) entitled Never Give a Trucker an Even Break, rehashed substantial amounts of stock footage from Duel in a story where Bill Bixby aids a woman trying to get her father’s truck back from hijackers. Amazingly, the episode manages to completely reverse the nature of the truck here where the truck is now being driven by the heroes of the show. Duel was also amusingly spoofed in a tv commercial for German car-manufacturer Audi, while 5-25-77 (2022) contains a number of quotes from the film.

Steven Spielberg’s subsequent genre films as director are:– LA 2017 (1971), Something Evil (tv movie, 1972), Jaws (1975), Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Twilight Zone – The Movie (1983), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Always (1989), Hook (1991), Jurassic Park (1993), The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), A.I. (Artificial Intelligence) (2001), Minority Report (2002), War of the Worlds (2005), Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), The Adventures of Tintin (2011), The BFG (2016) and Ready Player One (2018). Spielberg has also acted as executive producer on numerous films. Spielberg (2017) is a documentary about Spielberg,

Richard Matheson’s other genre works are:- The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) based on his own novel, Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations The House of Usher/The Fall of the House of Usher (1960), Pit and the Pendulum (1961), Tales of Terror (1962) and The Raven (1963), the Jules Verne adaptation Master of the World (1961), the occult film Night of the Eagle/Burn, Witch, Burn (1961), the Corman-produced mortician’s comedy The Comedy of Terrors (1963), The Last Man on Earth (1964) based on his novel I Am Legend concerning a world taken over by vampires, the Hammer psycho-thriller The Fanatic/Die, Die, My Darling (1965), the classic Hammer occult film The Devil Rides Out/The Devil’s Bride (1968), the historical biopic De Sade (1969), The Night Stalker (1972) and The Night Strangler (1973) tv movies, the ghost story The Legend of Hell House (1973), the tv adaptation of Dracula (1974), the tv movies Scream of the Wolf (1974), The Stranger Within (1974), Trilogy of Terror (1975), Dead of Night (1977), The Strange Possession of Mrs. Oliver (1977), the tv adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (1980), the time travel romance Somewhere in Time (1980) from his own novel, Jaws 3-D (1983) and Twilight Zone – The Movie (1983). Works based on his novels and stories are The Omega Man (1971) from I Am Legend, the afterlife fantasy What Dreams May Come (1998), the fine ghost story Stir of Echoes (1999), I Am Legend (2007), The Box (2009) and Real Steel (2011).

Trailer here