Crew

Director – Robert Zemeckis, Screenplay – Michael Goldenberg & James V. Hart, Based on the Novel Contact (1985) by Carl Sagan, Story – Ann Druyan & Carl Sagan, Producers – Steve Starkey & Robert Zemeckis, Photography – Don Burgess, Music – Alan Silvestri, Senior Visual Effects Supervisor – Ken Ralston, Visual Effects – Sony Pictures Imageworks Inc. (Supervisor – Stephen Rosenbaum), Additional Visual Effects – Big Sky Post, CIS Hollywood (Supervisor – Dr. Ken Jones), Industrial Light and Magic (Supervisor – Jim Mitchell), Pacific Ocean Digital, Warner Digital (Senior Supervisor – Michael Fink, Supervisor – Ariel Velasco Shaw) & Weta, Ltd, Special Effects Supervisor – Allen Hall, Production Design – Ed Verreaux. Production Company – Warner Brothers/South Side Amusement Company.

Cast

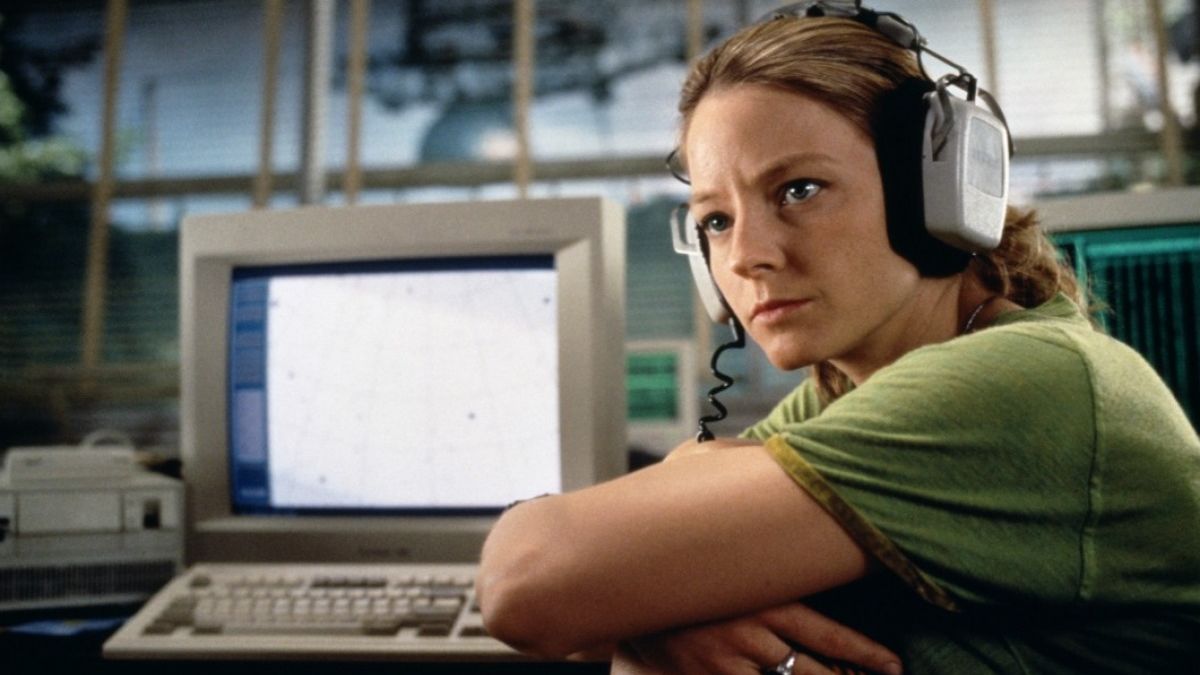

Jodie Foster (Ellie Arroway), Matthew McConaughey (Palmer Joss), Tom Skerritt (David Drumlin), James Woods (Michael Kitz), John Hurt (S.R. Hadden), David Morse (Ted Arroway), William Fichtner (Kent Clark), Angela Bassett (Rachel Constantine), Jena Malone (Young Ellie), Jake Busey (Joseph)

Plot

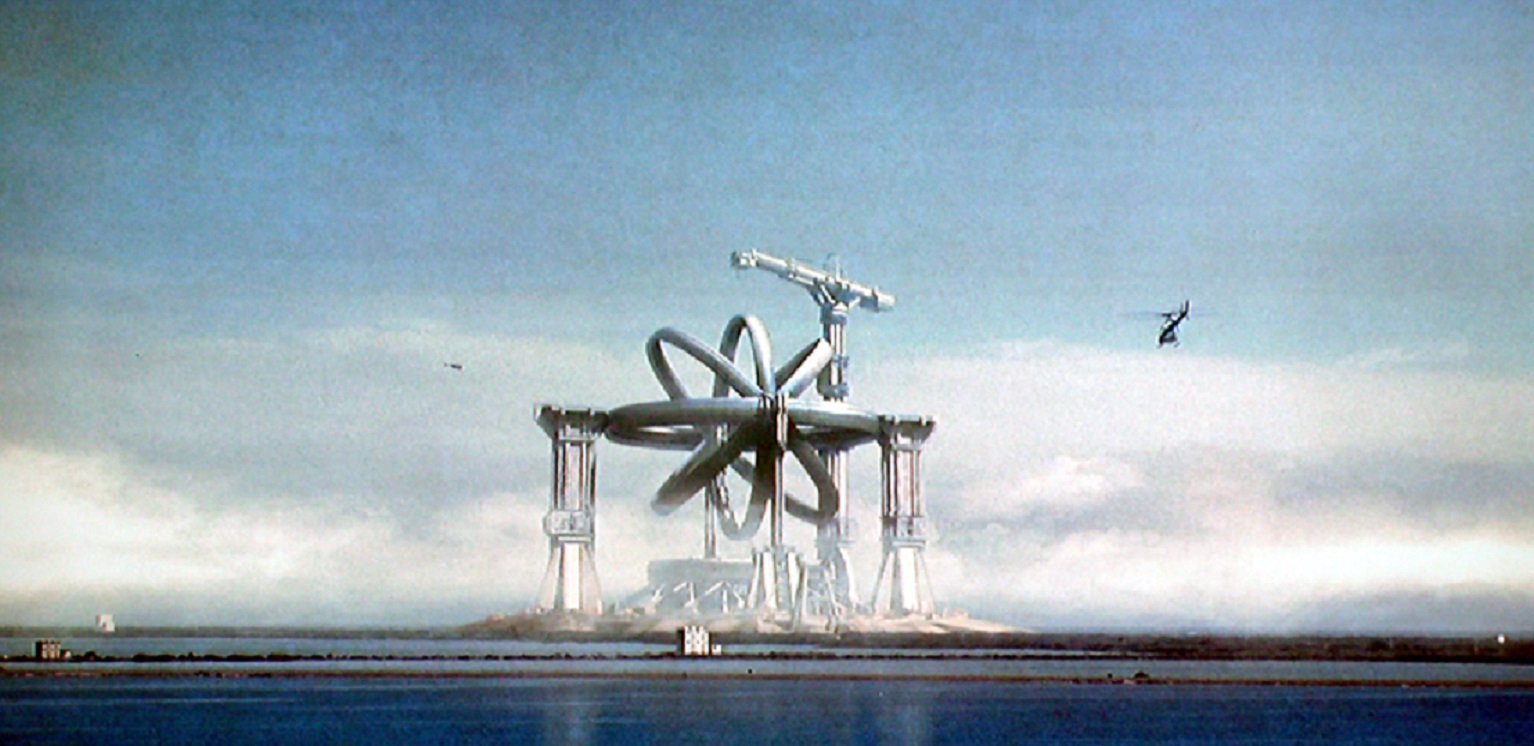

Eleanor or Ellie Arroway grows up with a childhood fascination with radio, believing that she might use it to communicate with her late mother in Heaven. As an adult, Ellie has become a radio astronomer specializing in SETI (the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence), searching bands of random intergalactic radio noise for any pattern that would suggest intelligence elsewhere in the universe. When the officious project head David Drumlin curtails her work at the Arecibo dish, Ellie after much legwork obtains funding from the enigmatic billionaire S.R. Hadden to lease radio telescope time from the government to continue her research privately. Suddenly they pick up a broadcast of non-random signals from the direction of the star Vega. These turn out to be coded prime numbers. This excites great government and military interest; however, Drumlin, now the national science advisor, comes in and commandeers the discovery. The message is found to contain a video signal of Adolf Hitler at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, which was the first television broadcast to be sent into space from Earth. Hidden inside the signal are found to be detailed engineering schematics. After much speculation, it is discovered that these are plans for the construction of a device for intergalactic travel. The Machine, as it is called, is built and there is heated competition to be the person who will go on the maiden voyage but the scheming Drumlin beats Ellie out for the role but a religious fanatic then blows The Machine up in a suicide bombing. However, Hadden has built a second Machine in secrecy and Ellie is chosen as the passenger. Launched, The Machine whisks her away through a network of wormholes to a planetary city circling Vega.

Carl Sagan (1934-96) was an astronomer who became the foremost science populist in the world during his lifetime, advocating an ardent belief in the possibility of and the search for extra-terrestrial life. Sagan published a number of popular science books, including Communications with Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (1973), Broca’s Brain (1974) and The Dragons of Eden (1978), which won a Pulitzer Prize. Sagan was even host of the PBS tv series Cosmos (1980), wherein he travelled through time and space in the time machine from The Time Machine (1960), giving illustrated lectures on various aspects of science. [Sagan had also earlier worked for Arthur C. Clarke as a science advisor on 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)].

Contact appeared to grow out of talks that Carl Sagan had with Francis Ford Coppola in the 1970s about creating a hard-science movie. (Indeed, Coppola later sued Sagan, demanding recognition on Contact). Officially at least, Sagan and wife Ann Druyan came up with the idea for Contact during the early 1980s at the behest of Lynda Obst, who had then worked as a producer on Flashdance (1983) and would go on to produce works like The Fisher King (1991), Sleepless in Seattle (1993), Abandon (2002) and Interstellar (2014). Lynda Obst inspired Sagan and Druyan to come up with a treatment based on Carl Sagan’s work on SETI. The Contact project floated around in development and then moved out of Lynda Obst’s hands and into those of Peter Guber, producer of Batman (1989). Under Guber’s hands, there were reportedly disastrous script rewrites, including the idea of Ellie Arroway having a son who sneaks along for the ride inside The Machine and the aliens arriving in big spaceships to hover over the Earth.

The film project fell through and Carl Sagan eventually published the idea as a novel Contact (1985). As a novel, Carl Sagan turned the story into a fascinating dialectic on the debate between religion and science. Indeed, Contact the novel is a work that seems driven very much by Carl Sagan’s own beliefs – Sagan was an advocate of science who clearly envied much about religion but could never accept its blind faith. The novel comes to a remarkable ending that shows Sagan wishing to find a synthesis of religion and science. One peculiar trivia note was that the Contact novel introduced the notion of a wormhole being used as a portal for intergalactic travel after Sagan approached physicist Kip Thorne to come up with a new idea for interstellar travel. This idea was taken up and popularised in a big way by Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993-9).

Subsequent to the publication of the novel, Contact was revived as a film project in the 1990s with George Miller, the director of Mad Max (1979) and sequels being attached for several years. George Miller brought Jodie Foster on board – she signed in 1994, saying that the script was one of the few that she considered interesting enough to appear in. Miller had originally cast Ralph Fiennes opposite her in the role of Palmer Joss. However, Warner Brothers considered that George Miller was dragging his feet too much – demanding too many script rewrites and sets not having been built by the film’s projected start date – and he was fired and replaced by Robert Zemeckis.

Robert Zemeckis is a director who emerged in the mid-1980s and since then has blossomed with a genuine flair for genre and mainstream commercial filmmaking. Zemeckis became a name to notice with the massive success of his fourth film as director Back to the Future (1985). He followed this with other hits like Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988) and the Academy Award winning Forrest Gump (1994). Zemeckis has always had a strong interest in pushing the envelope of effects technology in the films he makes – Roger Rabbit did radical things in mixing animation and live-action; Death Becomes Her (1992) was one of the first films of the CGI revolution; both Forrest Gump and Contact did extraordinarily clever things in their blending of filmed footage and newsreel material (with Contact causing a degree of controversy in using a digitised image of Bill Clinton inserted into its various press conferences); while The Polar Express (2004) became the first major film to be shot entirely in performance capture animation, something that Zemeckis seemed to want to specalise in for several years after.

Contact the film (of the novel of the idea for the film!) is faithful to Carl Sagan’s book for the most part, although does change the book in many ways. The major change the film makes is to turn the book into a $70 million film. Alas, Contact is not a story that easily sits as a $70 million film. Apart from the climactic journey to Vega, the book lacks big-budget effects and action sequences; it is that relative rarity of a good science-fiction story that works as story. So it becomes odd when the film tries to pump the book up into a big-budget film even when it does not require such. The Machine goes from a modest sphere in a hangar to a vast twirling structure replete with enormous energy discharges and massive special effects explosions. Indeed, the first twenty minutes or so of Contact become almost distracting in the film’s constant need to show off its big budget – there is hardly a shot that does not frame the drama against telescopic arrays, canyons or starry night skies.

Certainly, the special effects are impressive – the most dazzling being the opening shot that pulls back from the Earth, out through the solar system and right across the galaxy to the accompaniment of selected radio and tv fragments that subtly go backward in time until we reach a point where there is only pure silence, only for the film to then pull back from the galactic scape to reveal the entire shot is only something reflected in young Ellie’s eyeball. The sweep between the cosmic and the infinitesimal here is dazzling – something akin to Stanley Kubrick’s jump from bone to spaceship in 2001. However, none of this is necessary to the story and one cannot help but feel the story would have worked more absorbingly as a smaller, more intimate drama.

The most obvious change to the book is the character of Palmer Joss who goes from being a fundamentalist Christian leader (which Carl Sagan appears to have modelled on Jerry Falwell) to a more nebulous New Age minister (presumably so as not upset America’s evangelicals). Much more awkwardly, Joss is altered to be made into a love interest for Jodie Foster in the person of Matthew McConaughey, whose star was just emerging at the time that Contact was made. Alas, McConaughey’s casting is one of the biggest problems that one has with Contact. It is miscasting that fails on almost every levels – for a start, one fails to believe someone of Matthew McConaughey’s age (McConaughey was 28 at the time Contact came out) would have been able to earn respect as a major spiritual leader of the nation.

It is also hard to accept Joss as a character – the way the film writes him he never seems to represent any beliefs other than the nebulous notion of ‘religion’, everything he is exists only as a counterpoint to ask pointed questions about Ellie’s faith in science. Certainly, Contact bravely tries to delve into and analyse (even harmonise) the perpetually contentious divide between religion and science. Carl Sagan had the optimistic view that science could offer hope to humanity and evidence of a higher power (as seen in the ending of the book). However, the film mutes Sagan’s argument, notably in seeming too afraid to ever come out and name Palmer Joss as being a fundamentalist Christian. As a result, this makes Carl Sagan’s debate between religion and science into merely a debate between science and hazy New Age ‘spirituality’.

The journey to the stars also takes place in much more reverential and sentimental terms than the book – with a soundtrack of awe-filled choruses and with Jodie Foster being greeted by her dead father incarnated from her memories when she arrives. It is what you would imagine the Stargate journey in 2001 being turned into if 2001 had been made after E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982). (There are a number of remarkable resemblances to the 2001 Stargate journey – both here and in 2001, we have a sphere being pulled through a tunnel of stars to arrive at a clearly artificial and awkwardly unreal environment, and once there the promise from never-seen aliens of being able to undergo a radical shift of evolutionary consciousness as a species to take one’s place among the brotherhood of other races in the galaxy).

More interesting is the way that the film changes the book’s underlying message. The book seemed to yearn for a religious belief that could be found in science. However, the film drops the remarkable ending where the aliens suggest that Ellie look in the numbers of pi and the final scene where she uses a computer to generate pi to an extraordinary length and finds a string of non-random ones and zeroes that makes a circle pattern. (This was purportedly removed because the filmmakers thought that audiences would not know what pi was).

The film also subtly changes the voyage through the wormhole – it drops the four other scientists who accompany Ellie in the book, for instance. This is in order to manoeuvre the entire journey around to place Jodie Foster in the ironic position of realising that there is no proof of her journey ever having happened and that she has to accept some things as faith. Where Carl Sagan wanted to find religious belief on scientific grounds, the film ends up skewing this around to make the querulous statement that religion and science are just alternate forms of faith.

There is a strain of religion that runs through almost all alien contact films. Works like 2001, Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and E.T. see contact with other lifeforms in terms of a numinousness that passes all rational understanding and enters into awe. There often seems a thin line between this awe and religious belief, which is blurred altogether in films like The Black Hole (1979), Stalker (1979), Man Facing Southeast (1986), Event Horizon (1997) and Knowing (2009). In the real world, there has also been a thin line between religion and alien contact with the emergence of UFO cults like Heaven’s Gate and the Raelians, as well as the Church of Scientology, which transfer traditional religious elements of salvation, deliverance and reincarnation onto alien beings. It is as though the very notion of alien contact surpasses all common reference points that human culture has so the only fallback in terms of imagining what is out there is to reach for religious analogies.

The failing of many of these alien contact films is in inability to sufficiently imagine beyond all the wondrous lights to think of what kind of world other lifeforms must exist in. (The film here, for instance, ditches much of the book’s debate about what happens when the Machine arrives at Vega – in the book, the scientists ask numerous questions of the aliens and get a picture of the vast galactic culture that they live in). Contact, like Close Encounters and E.T., in effect reduces us to children at the feet of the universe. At most, Contact and 2001 suggest that we need to grow up as a species in order to achieve true communion with the universe. Most of these alien contact films are essentially Me Generation in nature. E.T. is a wondrous film about alien contact but at heart is a film about a lonely boy seeking a friend; beneath its alien visitor story, Starman (1984) is about a widow reconciling with her late husband; Cocoon (1985) is not concerned with alien contact but about geriatrics learning to feel young again.

Contact‘s vision of alien contact comes close to Solaris (1972) with its final image of the psychologist standing on the island in the middle of the ocean beside his recreated family dacha. Likewise here, Jodie Foster travels to the stars only to meet a virtual replica of her father where it seems the whole of her scientific quest throughout the film has been the unlikely notion of her having been driven to communicate with the stars because that is where her parents went when they died and that the universe has eventually come to grant her a reconciliation of sorts. In a way, you can see Contact as akin to an afterlife story – the warm fuzzy sort where someone ventures through the white light into the afterlife and the ghost of a loved one appears in bright lights and assures their still living ones that the world beyond is a wondrous place beyond mortal understanding, that one day they will be reunited but for the meantime they must return to the mundane world.

That said, Contact is one science-fiction film that has made an assiduous effort to root itself in credible science. Some have nitpicked aspects of the film – the fact that the real-life Siccoro radio telescope would not be the most suitable array that any SETI team could purchase time on but has been chosen more for the coolness of the image of Jodie Foster sitting in a field, tapping her laptop and seeing a giant dish rotate behind her. Jodie and colleague William Fichtner also seem to prefer aural means of detecting radio messages, which seems absurd considering that most astronomical computers can scan hundreds of wavelengths at once and humans only one at a time. One might also nitpick why the big deal about suicide capsules and the like – why don’t The Machine scientists conduct a test run – and why the big deal about a hoax being assumed at the end – could they simply not try to send another person through the wormhole? Considering that both Siccoro and Woomera were tracking the Vega signals, surely basic triangulation would show that the source of the signals was not a geosynchronous satellite as Kitz argues at the end? Such quibbles aside, Contact is one of the few science-fiction films that pays more than a good deal of lip service to credible science. There are no shortcuts with instant real-time messages to and back from the stars – the film credibly takes into account the vast difficulty of intergalactic distances. It is also one of the few science-fiction films where we actually see scientists engaged in the process of real (as opposed to imaginary wave of the wand) science.

Jodie Foster was always mentioned in the role of Ellie Arroway throughout all the various incarnations of Contact in the 1990s. It is hard to imagine any other actress in the role – one is unable to think of any other actress that projects serious determination of conviction and intellectual strength like Jodie Foster does. John Hurt often steals the film out from under her, seeming to be having the most fun one has seen him having on screen in ages.

Robert Zemeckis’s other films as director are:– I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978), Used Cars (1980), Romancing the Stone (1984); his time travel trilogy Back to the Future (1985), Back to the Future Part II (1989) and Back to the Future Part III (1990), Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988), Death Becomes Her (1992), Forrest Gump (1994), What Lies Beneath (2000), Cast Away (2000), The Polar Express (2004), Beowulf (2007), A Christmas Carol (2009), Flight (2012), Allied (2016), Welcome to Marwen (2018), The Witches (2020), Pinocchio (2022) and Here (2024). Zemeckis has also produced a large number of other genre films including the Tales from the Crypt (1989-96) cable tv horror anthology series, the two film spinoffs Tales from the Crypt Presents Demon Knight (1995) and Tales from the Crypt Presents Bordello of Blood (1996), Peter Jackson’s The Frighteners (1996), the voodoo film Ritual (2002), the animated Monster House (2006) and Mars Needs Moms (2011), the boxing robots film Real Steel (2011), the tv series’ Manifest (2018-22) about a planeload of temporally displaced passengers and Project Blue Book (2019-20) about the US Air Force’s true life UFO investigation department and the robot film Finch (2021). Zemeckis is one of the producing partners in Dark Castle Entertainment and under their banner has acted as producer for House on Haunted Hill (1999), Thir13en Ghosts (2001), Ghost Ship (2002), Gothika (2003), House of Wax (2005) and The Reaping (2007).

James V. Hart has also worked on the scripts for genre films such as Hook (1991), Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), Muppet Treasure Island (1996), Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story (2001), Tuck Everlasting (2002), Lara Croft, Tomb Raider: The Cradle of Life (2003), The Last Mimzy (2007) and Epic (2013).

(Nominee for Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actress (Jodie Foster), Best Supporting Actor (John Hurt) and Best Special Effects at this site’s Best of 1997 Awards).

Trailer here