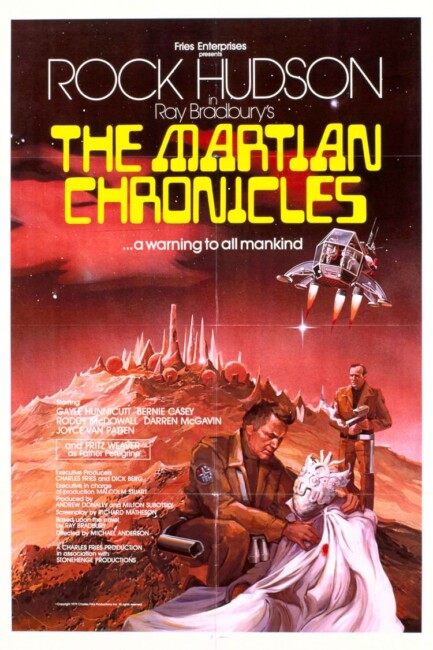

USA/UK. 1980.

Crew

Director – Michael Anderson, Teleplay – Richard Matheson, Based on the Novel by Ray Bradbury, Producers – Andrew Donally & Milton Subotsky, Photography – Ted Moore, Music – Stanley Myers, Electronic Music – Richard Harvey, Special Effects Supervisor – John Stears, Makeup Supervisor – George Frost, Production Design – Assheton Gorton. Production Company – Charles Fries Productions Inc/BBC/Polytel International/Stonehenge Productions.

Cast

Rock Hudson (Colonel John Wilder), Darren McGavin (Sam Parkhill), Bernie Casey (Captain Jeff Spender), Fritz Weaver (Father Peregrine), Roddy McDowall (Father Stone), Nicholas Campbell (Captain Arthur Black), Gayle Hunnicutt (Ruth Wilder), Christopher Connelly (Ben Driscoll), Barry Morse (Peter Hathaway), Bernadette Peters (Genevieve Seltzer), Wolfgang Reichmann (Leif Lustig), Michael Anderson Jr (David Lustig), Terence London (Martian Old One), Maggie Wright (Ylla), James Faulkner (Mr Y), Nyree Dawn Porter (Alice Hathaway), Anthony Pullen Shaw (Edward Black), John Cassady (Briggs), Maria Schell (Anna Lustig), Estelle Brody (Mrs Black), Jon Finch (Jesus Christ), Joyce Van Patten (Alma Parkhill)

Plot

Zeus I, the first manned mission to Mars, is launched in 1999. A Martian woman detects the approaching human astronauts in her dreams. Her jealous husband decides that they must be eliminated for the good of Mars. Some time later, a second expedition lands, only for the crew to discover that they have landed in a perfect facsimile of Green Fields, Illinois and that their loved ones are waiting. However, this turns out to be an illusion created by the Martians to trap and kill them. The third expedition, commanded by Colonel John Wilder, arrives to discover that the Martians have been wiped out by chickenpox. One of the crew, Jeff Spender, ventures into the abandoned Martian cities. He returns and tries to kill the members of the expedition in order to stop humanity polluting the magnificent Martian culture he has found there. Human colonists soon arrive en masse and begin establishing settlements across Mars. A Jesuit priest Father Peregrine ventures into the hills in the hope of converting the Martians rumoured to still be there. Colonist Leif Lustig and his wife are visited by their dead son, who is seemingly alive again, but realise that it is a Martian shape-changer. However, when the Martian accompanies them into town, it is inadvertently transformed into the missed loved ones of the people it encounters by picking up their telepathic impressions. As nuclear war threatens Earth, the colonists abandon Mars to return home. One of those who stays is former astronaut Sam Parkhill who runs a diner in the desert. Parkhill mistakenly kills a Martian and is pursued through the desert by other Martians. Also left behind, Ben Driscoll wanders the abandoned towns alone until he answers a ringing phone from another survivor Genevieve Seltzer. However, when they meet, he finds Genevieve to be less than he expects. After the nuclear devastation of Earth, Colonel Wilder returns to Mars. He is greeted by Peter Hathaway but puzzles over how Hathaway’s wife and daughter have not changed in twenty years. A meeting across time with the ghost of a Martian causes Wilder to contemplate how he and his family can adapt and make a new life on Mars.

Ray Bradbury (1920-2012) is one of genre writers that can justifiably be called a genuine American legend without the need for hyperbole. Bradbury started writing science-fiction, horror and fantasy stories in 1941 and produced classics novels like Fahrenheit 451 (1953), Something Wicked This Way Comes (1963) and short story collections such as Dark Carnival (1947), The Illustrated Man (1951), The Golden Apples of the Sun (1953), The October Country (1955), Dandelion Wine (1957) and I Sing the Body Electric (1969), among many others. Bradbury’s writing is often wistful and nostalgic – he has a distrust of change and progress, which puts him at odds with most other science-fiction writers, and an endless enthusiasm for smalltown boyhood and the ephemera of American popular culture. He has been called the Walt Whitman of science-fiction but the greatness of his body of work will always be his poetic voice and ability to conjure haunting imagery.

The Martian Chronicles (1950), retitled The Silver Locusts for British release, is Ray Bradbury’s most famous work. The book consists of fourteen stories and several prose poems that Ray Bradbury wrote between 1947-8 and should be considered more of a series of stories set around a shared venue than a novel. (Because of the piecemeal nature of stories, the description of the Martians changes throughout – in Ylla and The Earth Men, they are comic figures who are essentially domestic humans located on Mars; in And the Moon Still Be as Bright and after their death, they are ethereal creatures of incredible artistic and intellectual achievement; in The Third Expedition, they are quite sinister figures; while in The Fire Balloons, they are beings that have transcended their bodies altogether). The number of stories does vary depending on different published versions – Way in the Middle of the Air, a story about African Americans finding refuge from racial prejudice on Mars, is eliminated from later versions, and The Fire Balloons is included in all versions subsequent to the mini-series. Bradbury also wrote thirteen other Mars stories that do not appear in the book.

The Martian Chronicles has become a classic because of Bradbury’s elegiac evocation of a Mars of fantasy (as opposed to scientific reality). It is one of the genuine classic works of literary science-fiction (even though Bradbury oddly denied that it ever was a work of science-fiction). Like H.G. Wells with The War of the Worlds (1898) and Edgar Rice Burroughs with the John Carter stories, Bradbury has drawn from Giovanni Schiaparelli’s fanciful 19th Century speculations of a Mars crisscrossed by canals. The difference to these other works is that The Martian Chronicles was published at a time when this was known to be scientifically unfeasible, thus becomes a retro science-fiction adventure, a romance of Mars. Added to this, Bradbury has drawn parallels for human colonisation from the settling of the Western frontier in the US. Like Wells at the end of The War of the Worlds, Bradbury takes the idea that human diseases killed off the Martians, both of which reflect the way settlers of the West devastated American Indian populations with smallpox.

A regular theme that runs through Ray Bradbury’s work is how humanity banally or selfishly misuses the wondrous. Mars is seen as an ideal society that venerates the arts, philosophy, intellectual achievement and respect of nature. The sadness of the book is the way in which humanity has heedlessly destroyed a millenia-old Martian culture that was the height of moral, artistic and intellectual sophistication. There is also the theme throughout the book that in a world where telepathy and mental illusion exists, humanity can find its longings, losses and sentiments made manifest, but how this also makes people vulnerable to those illusions. Bradbury also acutely portrays how people hold onto the past and prefer comforting illusions to reality – in The Long Years, Hathaway surrounds himself with android recreations of his wife and daughter rather than face their death; the Martian in The Martian becomes a manifestation of people’s missed ones; or how the illusion of the perfect American small town becomes something the astronauts willingly surrender to and the Martians are able to use as a deadly trap in The Third Expedition.

A film adaptation of The Martian Chronicles had been touted since at least the late 1950s. The major problem that seems to have defeated others has been in how to turn a collection of stories into a single film. This tv mini-series adaptation was eventually greenlit amidst the big science-fiction boom that came in the aftermath of Star Wars (1977). The script was given to Richard Matheson, a genre veteran who has written a number of classic genre films and books. (See below for Richard Matheson’s other genre works).

Matheson’s script cuts and changes various of the stories from the book. He eliminates some of the slighter stories like The Green Morning and The Wilderness. Some of the less cinematic and more difficult ideas have been cut – like Usher II about a man who has built a castle with elaborate traps designed to kill a group of book censors; There Will Come Soft Rains, which is more a prose poem than a story concerning an automated house that continues on in the aftermath of the nuclear holocaust – and crucially features no human characters (there is the slight suggestion of this here in the absurdly mannered portrait of nuclear war where people become green glowing blobs and then disappear but the entire room is left unaffected); while Way in the Middle of the Air goes because its theme – African Americans welcome Mars for freedom from lynch gangs – had become dated by 1980.

I was a little disappointed to see that The Earth Men, concerning the second expedition who land and are shot because they are thought to be telepathic hallucinations from a mentally ill Martian, had been excised for reasons unclear, as it is one of the wittiest stories in the collection. Night Meeting – a slighter story takes place early in the book – is moved to later in the show to become an encounter between Rock Hudson and a Martian across time on a desolate Mars. The mini-series also adds one of Bradbury’s Mars stories that does not appear in The Martian Chronicles (and instead comes from The Illustrated Man, although has been added to all reprints of the book subsequent to the mini-series) – The Fire Balloons concerning two Jesuit priests and their meeting with the disembodied Martian spirits.

The most notable feature of the mini-series has been the effort made by Richard Matheson’s script to stretch what is a series of short stories set around a common venue into a single dramatic narrative. This is done by winding Rock Hudson’s Captain Wilder into most of the stories – either by making him the central character or else having him pass through in one way or another. The effect often feels awkward and contrived. By contrast in the book, Captain Wilder only appears as a character in And the Moon Still Be as Bright and The Long Years, and is mentioned as having been sent to outer reaches of the solar system in one other story.

Other continuing characters are obviously written and given no other depths than is required to set them up for their individual stories later in the show. Thus Bernie Casey’s Spender is written as a loose cannon worried about polluting the Martian culture before they have even left Earth and discovered the presence of any Martians, while Darren McGavin’s Parkhill is constantly dreaming of setting up his diner in the middle of nowhere.

One feels that the mini-series would have worked far better in not trying to tell The Martian Chronicles as a single six-hour, three-part drama but as a series of individual half-hour episodes along the lines of the excellent The Ray Bradbury Theater (1986-92) anthology tv series. (The Ray Bradbury Theater also notedly adapted a number of stories from The Martian Chronicles – And the Moon Still Be as Bright, The Third Expedition, The Martian, The Silent Towns and Usher II – and did a far better job of telling them).

The unfortunate failing of The Martian Chronicles is not Richard Matheson’s script, which could easily have worked despite the ungainly narrative structure. Rather the failing is all due to the director assigned to the project – Michael Anderson. The British-born Anderson began directing in the 1950s with big-budget films like The Dam Busters (1954) and Around the World in 80 Days (1956). However, Anderson’s run with genre films has been disastrous – see the likes of 1984 (1956), Doc Savage – The Man of Bronze (1975), Logan’s Run (1976), Bells/Murder By Phone (1981) and Millennium (1989), as well Second Time Lucky (1984), which may well be one of the worst films ever made. In all cases, these suffer from a leaden heavy-handedness and flatly literal lack of imagination upon Anderson’s part. (See below for Michael Anderson’s other genre credits).

Anderson’s pace in the mini-series is slow moving and pedestrian. In stories like The Third Expedition, The Martian and The Long Years, his plodding hand causes the respective twist ending of each story to be tipped off well in advance. The special effects are extremely shoddy at times – the mini-series almost entirely shoots itself in the foot in the opening scene with the incredibly poor model work as a lander touches down upon the Martian surface.

It’s possible that the single worst aspect of the mini-series is some of the casting. Rock Hudson does his stolid leading man thing and is completely stiff throughout. That said, Hudson is at least serviceable. Much worse is the agonisingly painful effort at sincerity that comes in Fritz Weaver’s performance as Father Peregrine. Although the worst performance of all is the lunatically hopped-up one given by Darren McGavin. McGavin gives the impression that he had no clue what the show was about and decided to play the whole thing for maximum silliness. The most cringe-worthy moment in the entire series is surely the sight of McGavin decked out in a glitter cowboy suit that makes him look like a cross between a country-and-western singer and a used car salesman. The Off Season, McGavin’s one starring story, is not unexpectedly the worst in the show. The model effects when it comes to the race of the sandships, which make them look like decorations on a wedding cake, are downright embarrassing, and the sight of Darren McGavin on the mock-up of a sandship foredeck in his neon cowboy suit pretending to navigate by pulling ropes almost entirely kills all suspension of disbelief. Furthermore, the hero of this story is a xenophobic redneck with low intelligence – after the entire theme of The Martian Chronicles is how we fail to appreciate Mars for its beauty and culture of the mind, it seems ridiculous to be expected to have sympathy for an idiot who starts blindly shooting at the handful of remaining Martians.

The other dreadful story in the show is The Silent Towns with Christopher Connelly as a lonely miner who meets the one other person left on the planet in the form of Bernadette Peters who turns out to be way less than expected. Richard Matheson at least tries to make the story work by tossing out the reasons that Ben had for fleeing from Genevieve in Bradbury’s short story – she was overweight and clingy – but the characterisation of Genevieve here is equally as sexist – she is a vain, air-headed blonde who is completely obsessed with her looks and expects to be waited on. Michael Anderson keeps overstressing her self-absorption to the point that it becomes like a screaming neon red underline and you wish someone would grab him by the collar and explain the concept of understatement. This is one story that should easily have been excised from the adaptation.

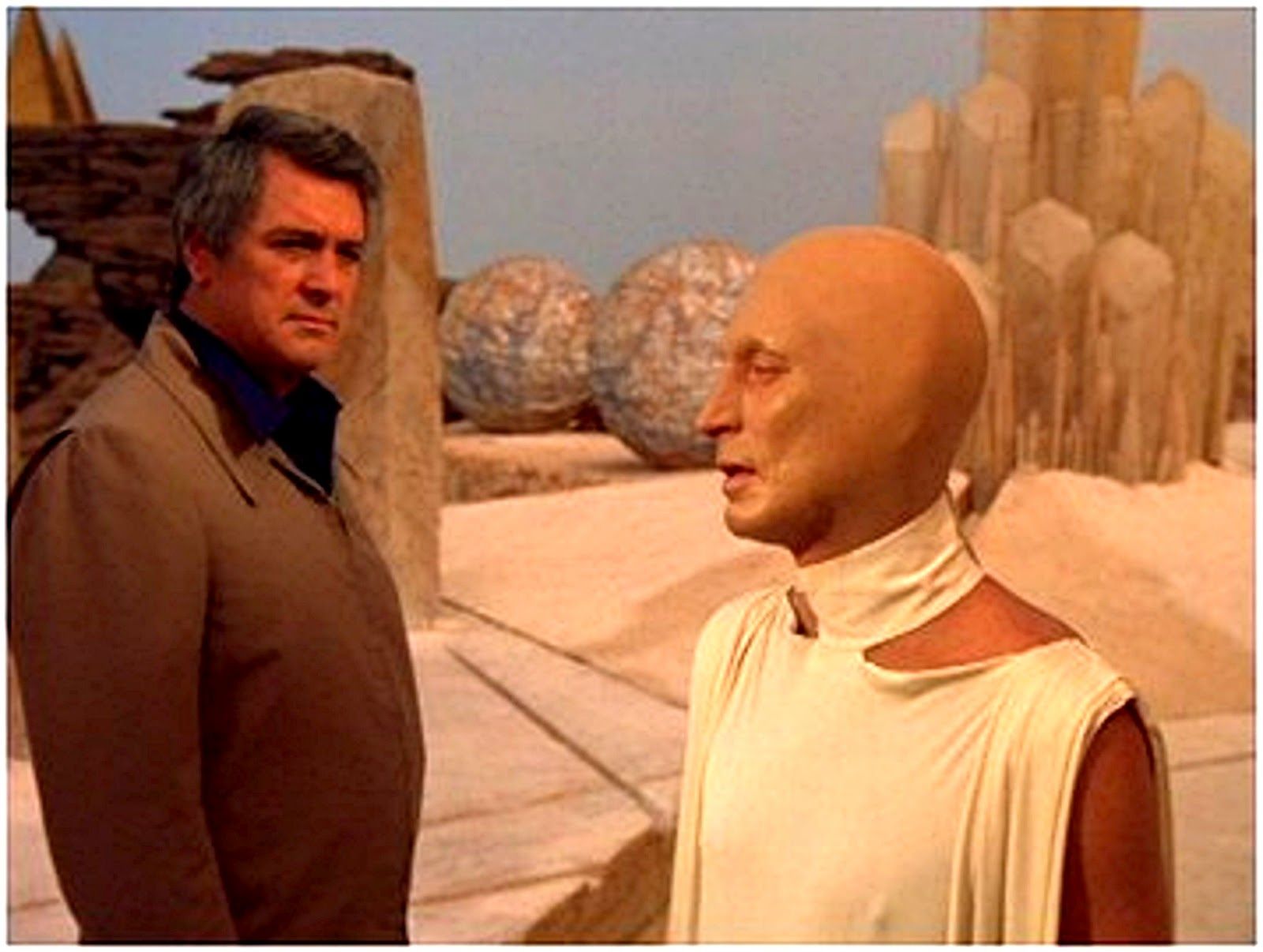

There are times that The Martian Chronicles does work in spite of Michael Anderson’s leaden hand. The series is especially good at capturing the ethereal alienness of the Martians – in bald heads with glittering gold eyes and no ears; in flowing white Grecian robes or a mask that strikingly consists of a giant V with a single eye set in the centre; the strangely fluted handguns; their crystalline houses; and the cities consisting of dolmens carved in stone balls, pyramids and wedge shapes, all shot amid the almost pure white sands of Malta. The adaptation of the opening story Ylla sets the stage well and is an almost perfect version of the story up on screen as it is, with the narrator delivering wonderfully nonchalant phrases like “Mr K heard his book,” which is the essence of good science-fiction.

Some of the stories have a modest effectiveness, particularly when they are playing with the theme of illusion and identity. One of the best episodes is the adaptation of The Third Expedition, which, though it unsubtly gives the surprise away, effectively communicates the puzzling strangeness of the astronauts arriving on Mars to find a perfect simulation of rural smalltown Illinois created out of their memories. I particularly liked the end scene of the story with the townspeople conducting a funeral service as the voiceover explains how the Martians enacted a ceremony that was alien to them. The other story that works not too badly is The Martian with one lone Martian being torn every way and transformed into the loved ones of everybody it encounters as it runs through the town.

The principal failing of the mini-series is a mismatch of opposing talents. Ray Bradbury was a writer whose work turns on the soft imagery, the play of a word and rich, often overripe allegory. Bradbury was a nostalgist who pined for a lost culture of the mind – for him, The Martian Chronicles was largely a work about the death of the imagination and its supplantation by the crassness of unheeding mass culture. Landed with the task of translating Ray Bradbury’s work is Michael Anderson – a director who never encountered a piece of imagery or an analogy that he did not feel he needed to explain away until even the most dense five year-old in the audience understood what was meant.

Other Ray Bradbury screen adaptations include:– the classic atomic monster movie The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) from Bradbury’s short story The Foghorn; the alien invader classic It Came from Outer Space (1953) from his original screenplay; Francois Truffaut’s adaptation of Fahrenheit 451 (1966); the anthology The Illustrated Man (1969); the tv movie The Electric Grandmother (1980); the screenplay for the fine Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983) from his own novel; his screenplay for the animated adaptation of the classic comic-strip Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989); the tv anthology series The Ray Bradbury Theater (1986-92) where Bradbury adapted his own stories and hosted the series; the screenplay for the animated children’s film The Halloween Tree (1993); Stuart Gordon’s adaptation of The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit (1998) about a seemingly magical suit; A Sound of Thunder (2005) based on Bradbury’s classic time travel story; Chrysalis (2008) where a man mutates into another lifeform; and the tv movie remake of Fahrenheit 451 (2018).

Michael Anderson’s other genre films include an adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984 (1956); The Shoes of the Fisherman (1968), a political thriller concerning a near-future Pope; Doc Savage, The Man of Bronze (1975), based on the pulp hero; the dystopian sf film Logan’s Run (1976); the killer whale film Orca (1977); the psycho-thriller Dominique (1978); Bells/Murder by Phone/The Calling (1981) about killer telephone calls; the excruciating Adam and Eve softcore comedy Second Time Lucky (1984); the John Varley time travel film Millennium (1989); the tv movie remake of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1997); and The New Adventures of Pinocchio (1999).

Richard Matheson is a noted genre screenwriter and novelist. His other genre works include The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) based on his own novel, Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations The House of Usher/The Fall of the House of Usher (1960), Pit and the Pendulum (1961), Tales of Terror (1962) and The Raven (1963), the Jules Verne adaptation Master of the World (1961), the occult film Night of the Eagle/Burn, Witch, Burn (1961), the Corman-produced mortician’s comedy The Comedy of Terrors (1963), The Last Man on Earth (1964) based on his novel I Am Legend (1954) concerning a world taken over by vampires, the Hammer psycho-thriller The Fanatic/Die, Die, My Darling (1965), the classic Hammer occult film The Devil Rides Out/The Devil’s Bride (1968), the historical biopic De Sade (1969), Steven Spielberg’s first film Duel (1971), The Night Stalker (1972) and The Night Strangler (1973) tv movies, the haunted house film The Legend of Hell House (1973) from his novel, the tv adaptation of Dracula (1974), the tv movies Scream of the Wolf (1974), The Stranger Within (1974), Trilogy of Terror (1975), Dead of Night (1977) and The Strange Possession of Mrs. Oliver (1977), the time travel romance Somewhere in Time (1980) from his own novel, Jaws 3-D (1983), Twilight Zone – The Movie (1983), and numerous classic episodes of The Twilight Zone, Thriller and Star Trek. Works based on his novels and stories are The Omega Man (1971) from his I Am Legend, the afterlife fantasy What Dreams May Come (1998), the fine ghost story Stir of Echoes (1999), I Am Legend (2007), The Box (2009) and Real Steel (2011).

Trailer here