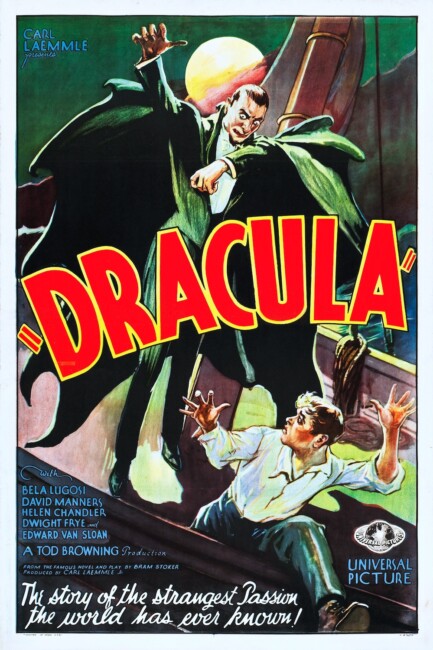

USA. 1931.

Crew

Director – Tod Browning, Screenplay – Garrett Fort, Additional Dialogue – Dudley Murphy, Based on the Play by John L. Balderston & Hamilton Deane, Based on the Novel by Bram Stoker, Producer – Carl Laemmle Jr, Photography (b&w) – Karl Freund, Makeup – Jack Pierce, Art Direction – Charles D. Hall. Production Company – Universal.

Cast

Bela Lugosi (Count Dracula), Edward Van Sloan (Abraham Van Helsing), Helen Chandler (Mina Seward), Dwight Frye (Renfield), David Manners (John Harker), Frances Dade (Lucy Weston), Herbert Bunston (Dr Seward)

Plot

The lawyer Renfield travels to Castle Dracula in Transylvania to arrange the lease of Carfax Abbey in England for Count Dracula. There he is welcomed by the urbane Dracula. Some time later, the ship Vesta crashes in Whitby Harbour near Carfax Abbey and Renfield is found aboard raving mad and eating rats and insects. He is placed in the asylum of Dr Seward. Dracula then appears. Lucy Weston is attracted to him and that night a bat appears at her window, transforming into Dracula and she is found dead, drained of her blood. As Dracula next directs his attentions towards Seward’s daughter Mina, the psychiatrist Van Helsing realises that Dracula is a vampire and determines to stop him.

More than any other adaptation of the Bram Stoker novel Dracula (1897), it is this 1931 version that has created an indelible image of the vampire – that of the East European-accented figure in cape and dinner-suit. It is an image that casts its shadow to this day – you can almost be guaranteed to see one such vampire at any costume party and you can buy dozens of such figures in Halloween stores. Unfortunately, when one gets around the mythology that surrounds the film and its star Bela Lugosi, pumped up by neophytic magazines like Famous Monsters of Filmland (1958-82), one finds a film that is dated, actionless and frequently laughable. A classic Dracula undeniably is; a great film is a whole other matter.

Probably the film’s first mistake was in fashioning itself from the stage adaptation of the book rather than directly from the 1897 Bram Stoker novel. This, written by Hamilton Deane, who grew up near Bram Stoker and family in Ireland and later went to work for the Henry Irving stage company that Bram did for many years, originally appeared in 1924 in Derby in England Deane played the role of Van Helsing on stage. This enjoyed some success before being brought to the US in 1927 in a version re-adapted by John L. Balderston and starring an actor by the name of Bela Lugosi (and with Edward Van Sloan playing Van Helsing).

Adapting the play was seen as a cost-cutting measure for Universal that allowed the film to be told using fewer sets and locations than a straight adaptation of the book would have. This does give it certain advantages such as making Dracula a much more central character than he is in the book. However, little attempt has been made to expand the play out or to go back to the book’s much wider canvas.

Tod Browning’s direction is very stagy in tone – the camera statically wanders around the giant sets but rarely moves into closeup or piecemeal editing. (Part of the problem here was the newness of recording equipment in the sound era, which was large and bulky, meaning that it had to be kept close to the camera and that the camera was no longer free to move about). The bat attack on Dwight Frye and the scene where the bat turns into Bela Lugosi are conducted just as they would be on the stage – the bat appears behind a set of French windows while the camera remains in static wide-angle on the other side of the set, the bat vanishes and then Lugosi appears from behind a dividing wall after Frye falls. Even the final dispatch of Dracula is conducted off-screen, the staking heard as only a single crunch and Dracula going with no more than a gasp. Compared to Dracula’s spectacular death in the 1958 Hammer remake, this seems ludicrously inadequate.

The film seems only a perfunctory reading of the Dracula story – the film has a runtime of 75 minutes. There is little drama to it – the attack on Lucy, for instance, cuts from Bela Lugosi leeringly moving across her bedroom towards her, to her dead on the operating table and Van Helsing shrugging and saying that the blood transfusions failed to work. There is little horror to the story – in fact, this may well be the only non-comedic vampire film where no blood is shown – while scenes like the captain tied to the wheel of the Vesta are only shown in silhouette.

The major holdover from the stage version was Bela Lugosi in the title role. Lugosi, who was a matinee idol in his native Hungary, arrived in the US in 1921 knowing no English and obtained the lead role in the stage adaptation of Dracula, where he is reputed to have learned the part phonetically. The stage version was a great success. A film version had originally been planned to have been directed by Tod Browning and starring Lon Chaney [Sr]. Tod Browning and Lon Chaney had collaborated on a number of bizarre and weird films during the silent era, all of which featured Chaney undergoing an extraordinary physical transformation to give a performance. Alas Chaney died of throat cancer in 1930 and so Tod Browning replaced him with Bela Lugosi who had previously appeared as the police inspector in Browning’s talkie whodunnit The Thirteenth Chair (1929).

Certainly, the claim that Bela Lugosi learned the part phonetically gains much credence here. He gives the dialogue a singsong elocution that comes entirely independent of natural emphasis of speech. He plays in a series of wildly over-the-top smirking mugs and reactionary double-takes – every expression seems to come with great agony. He is like a villain out of an illustration for a 19th Century Gothic novel, lurking across rooms towards victims with exaggerated movement that is almost laughable in its embellishment. In pasty-face, made-up lips, hair slicked back to emphasise his oversized lug ears and eyes illuminated in a sharp band of light, Lugosi is something more alien and weird than most science-fiction ever gets. The lines come thick and arch – “To die, to be really dead, that must be glorious. There are worse things than death” – all punctuated by Lugosi’s accent and weirdly unnatural pauses in the middle of sentences, sometimes even in the middle of words. It is a truly fascinating performance – it is ham-acting at the worst it ever gets.

Whatever one might say about Bela Lugosi’s performance, his Dracula was influential – it is still Lugosi’s performance that every vampire caricature takes itself from. Dracula was enough to typecast Lugosi as a B-movie villain, something that dogged the rest of his career. Even though he polished his subsequent performances, Lugosi still retained the same thick European accent and leering menace and delivered all other parts, straight or otherwise, exactly the same way. Lugosi managed to get a number of A-parts during the 1930s horror boom but by the 1940s was reduced to playing in poverty row studio mad scientist films and by the 1950s had sunk to the role of the star player in the Edward D. Wood Jr freakshow, before his death in 1956. All other performances in the film are equally over-the-top – from the deadly emphatic intonation of Edward Van Sloan behind his bug-eyed glasses to Dwight Frye of unsettling laugh and blackout eye makeup conducting wild theatrics every time he opens his mouth.

Almost despite itself, the film manages to create a certain atmosphere. The opening has some imaginative moments with bats driving coaches and Dracula’s wives in long white trains coming after Frye. The Transylvanian scenes are usually celebrated as the best part of the film, but the sequence fails to succeed much because it is too stagy, the drama abruptly condensed and the scenery flat and cardboard. The best scenes are the ones set at the asylum – particularly the face-off between Bela Lugosi and Edward Van Sloan, with Lugosi attempting to bend Van Sloan’s will with his hypnotic powers but Van Sloan managing to resist and pull a crucifix to send Lugosi scurrying.

Other scenes momentarily shine – Renfield’s description of Dracula waiting for him outside his window – an army of rats opening up with him at their midst; Mina’s attempt to seduce the film’s rather thick Harker, begging him to remove the wolfsbane while fixing on his throat with a peculiarly unsettling glint of eyes. However, in terms of the film this could have been and certainly when compared to the other great classics that were being made by Universal at the same time – especially the film’s companion piece Frankenstein (1931) – Dracula is a heavy disappointment.

There were two sequels, the quite good Dracula’s Daughter (1936) and the dull Son of Dracula (1943). Bela Lugosi appears in neither of these. In the 1940s, Dracula appeared in Universal’s various monster team-ups beginning with House of Frankenstein (1944) and then House of Dracula (1945), where he was played by John Carradine. Bela Lugosi returned to the role for Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948), although by now Dracula was played for outright laughs.

Other adaptations of Dracula are:– the uncredited classic German silent Nosferatu (1922); Hammer’s classic Dracula/The Horror of Dracula (1958) with Christopher Lee; Dracula in Pakistan (1967), an uncredited remake of the Hammer film; Count Dracula (1970), a cheap continental production that also featured Lee; Dracula (1974), a cinematically-released tv movie starring Jack Palance; Count Dracula (1977), a BBC tv mini-series featuring Louis Jourdan; Dracula (1979), a lush big-budget remake starring Frank Langella; Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) with Klaus Kinski; Francis Ford Coppola’s visually ravishing Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) featuring Gary Oldman; the modernised Italian-German Dracula (2002) starring Patrick Bergin; Guy Maddin’s silent ballet adaptation Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary (2002); the BBC tv movie Dracula (2006) with Marc Warren; the low-budget modernised Dracula (2009); Dario Argento’s Dracula (2012) with Thomas Kretschmann as Dracula; the low-budget Canadian Terror of Dracula (2012) with director Anthony D.P. Mann as Dracula; the tv series Dracula (2013-4) with Jonathan Rhys Meyers; the BBC mini-series Dracula (2020) starring Claes Bang; Bram Stoker’s Van Helsing (2021), which actually features no Dracula; The Asylum’s Dracula: The Original Living Vampire (2022) with Jake Herbert; and the remake of Nosferatu (2024) with Bill Skarsgård. At the same time as the Lugosi Dracula, a Spanish language version Dracula (1931) starring Carlos Villarias was shot for Latino audiences on the same sets and using the same script translated into Spanish. For many years, this held a legendary reputation as being superior to this one and it has surfaced on video/dvd in recent years. The Lugosi Dracula was also substantially parodied in Mel Brooks’s Dracula: Dead and Loving It (1995).

Director Tod Browning’s other genre films are:– the extraordinarily perverse love and amputation story The Unknown (1927); the lost vampire film London After Midnight (1927); the classic Freaks (1932) about the lives of circus deformities; the London After Midnight sound remake Mark of the Vampire (1935); and the miniaturised people film The Devil-Doll (1936).

Trailer here