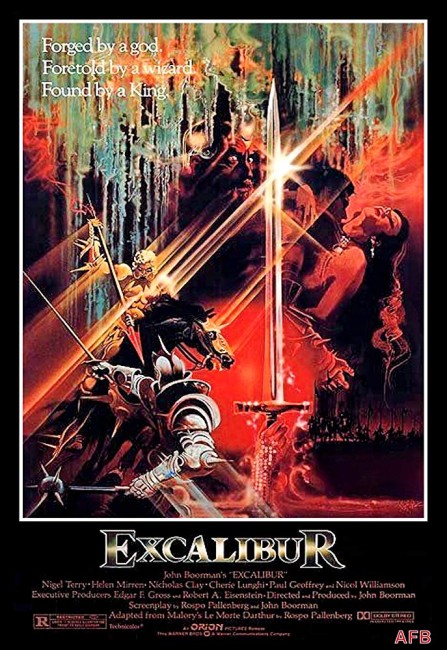

UK. 1981.

Crew

Director/Producer – John Boorman, Screenplay – John Boorman & Rospo Pallenberg, Adaptation – Rospo Pallenberg, Based on La Morte d’Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory, Photography – Alex Thomson, Music – Trevor Jones, Special Effects – Peter Hutchinson & Alan Whibley, Makeup – Anna Dayhurst & Basil Newall, Production Design – Anthony Pratt. Production Company – Orion.

Cast

Nigel Terry (Arthur), Nicol Williamson (Merlin), Helen Mirren (Morgana), Nicholas Clay (Lancelot), Cherie Lunghi (Guenevere), Paul Geoffrey (Perceval), Robert Addie (Mordred), Gabriel Byrne (Uther Pendragon), Katrine Boorman (Igraine), Corin Redgrave (Duke of Cornwall)

Plot

Aided by the wizard Merlin, Uther Pendragon uses the sword Excalibur, given to him by the Lady of the Lake, to unite England as one land and become its king. However, Uther loses his crown through desire for his rival’s wife Igraine. In his dying breath, Uther pushes Excalibur into a stone from which it cannot be removed except by the rightful heir to the throne. Several years later, the sword is unwittingly removed by Arthur, who is Uther’s son, born to Igraine, who is working as a knight’s page and is merely seeking to replace his master’s sword after it is stolen. Immediately crowned, Arthur unites the land as one again under the guidance of Merlin and creates the Round Table to bring the noblest knights together. However, the honour of the Round Table becomes corrupted when the knight Lancelot falls in love with Arthur’s wife Guenevere. Arthur’s half-sister, the sorceress Morgana, then uses the black arts to seduce Arthur. She gives birth to a son Mordred whom she raises to usurp Arthur. Meanwhile, the land, infected by Arthur’s moral sickness, falls into decay. The only cure is for the knights to go upon a quest to find the Holy Grail in order to heal Arthur.

The Arthurian legends are probably the most enduring mythic cycle in the English language. Although there is no clear proof that Arthur ever existed, it is believed that he may have been a general who managed to unite large parts of Britain after a decisive battle over the Saxons in the 5th Century A.D. That much is supposition but it has not stopped an extraordinary body of mythology growing up around him.

The story of Arthur began to emerge in Welsh oral traditions around the 10-11th Centuries and was first written down in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain (1136), an embellishment of the oral traditions that created a fanciful account of the reign of Arthur. Morgan-le-Fay and Mordred are present in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s stories but there is no incestuous relationship, while Arthur’s sword is named Caliburnus and there is no magic in the story yet. It was Geoffrey of Monmouth who brought the character of Merlin into the stories – although he later found that the character on whom he had based Merlin, Myrddin Wyllt, had lived over a generation later than Arthur was supposed to have, not that that stopped Geoffrey going onto tell further stories about Merlin’s origins.

The story of Arthur began to grow in the Mediaeval French royal court where it was considerably more embellished and magic added. The Norman monk Wace created the concept of Round Table. However, it was Chretien de Troyes, around 40 years after Geoffrey of Monmouth, who produced several volumes in which he introduced the characters of Lancelot (and his and Guenevere’s infidelity), Perceval and the Holy Grail. It took another writer Robert de Boron to link the Holy Grail to its specifically Christian origins, as well as introduce the concept of the Sword in the Stone. Many other writers during this period expanded side stories out around the central mythology, most notably the stories of Tristan and Isolde and that of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. However, it was Thomas Malory whose Le Morte d’Arthur (1485) brought together the Arthurian legends as we know them today together. All modern interpretations of the Arthurian legends draw directly upon Malory.

There had been a number of tentative cinematic stabs at the Arthurian legends prior to Excalibur – the ponderous non-fantastical Cinemascope spectacle Knights of the Round Table (1954), Disney’s The Sword in the Stone (1963), the equally ponderous musical Camelot (1967) and arthouse variations such as Robert Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac (1974) and Eric Rohmer’s acclaimed Perceval Le Gallois (1977). (See below for other filmed variations of the Arthurian legends).

Enter John Boorman, the acclaimed director of the likes of Point Blank (1967), Hell in the Pacific (1968), Deliverance (1972) and Zardoz (1974). John Boorman had wanted to make an adaptation of the Arthurian legends for fifteen years prior to this. Indeed, Boorman made the interesting claim in an interview that every film he has made has been some reflection of the Arthurian legends, from the grail quest, to the concept of chivalry to the relationship between man and nature. Intriguingly, Boorman also attempted during the 1970s to mount a production of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (1954-6) but could never find a means of scaling the books down to tell as a single film. (Excalibur makes interesting comparison to Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) and sequels and it is intriguing to speculate what Lord of the Rings might have emerged like had it instead come under John Boorman’s hand).

There is certainly enough material here for two or three films and Excalibur seems to be straining in trying to pack the entire Arthurian cycle into 140 minutes. Boorman plays around with Thomas Malory a little – Perceval takes over Galahad’s role and is the one who completes the Grail Quest, the stories about the Lance of Longinus and Morgan-le-Fay’s theft of Excalibur’s scabbard are excised (as they have been from all subsequent film versions).

That is less important though as Boorman takes the story back into the rich swim of mythology that birthed it. The aforementioned adaptations and almost all since are pedestrian, literalistic adaptations that concern themselves with either the political intrigue of the kingdom, the romantic story or banal displays of magic. John Boorman by contrast is interested in the ideas that make up the myth – the concept of chivalry, the concept of nationhood united under the king’s physical/moral health and pagan religion’s slow occlusion and usurpation by Christianity. The mythic resonances in Excalibur are extraordinarily rich.

Excalibur has a crazy rapturousness to it. It overflows with compelling, impassioned imagery. It is all beautifully shot in lush Irish landscapes and filled with extraordinary images of knights in beaten gold armour, woodland weddings draped in flora, battles set against beautiful red sunsets, the Lady in the Lake floating supine in the midst of a riverbed. The image of Arthur being knighted in the midst of a river is a remarkably moving one. Trevor Williams scores the film with selections from Wagner and Orff, which adds a wild, primal passion – rarely has the use of classical excerpts been so well chosen in a film.

John Boorman has also determined to make a vision of the Arthurian legends that doesn’t befall the cliches of the stuffed doublet Mediaevalism of Knights of the Round Table, Camelot and the Prince Valiant comic-strip, of merely being extras in page-boy haircuts and standard costumes from central casting. From the moment the film opens in the midst of a brutal bloody battle where we see arms hacked off, this is clearly a different vision of the Middle Ages, one that is rooted in a grimy realism. Many jumped on the fact that the styles of armour are wildly anachronistic but this is relatively unimportant, quite possibly deliberate – John Boorman is not setting out to make an historical film, the legend of King Arthur has rarely ever had anything to do with historical realism and Excalibur is clearly intended to takes place in a mythic neverwhen.

There is a time when Excalibur inevitably spills over and turns into almost baggy-pants burlesque, most notably Nicol Williamson’s performance as Merlin, which strides between wild overacting and a portentous wisdom. Some regard the performance as silly but when Nicol Williamson does succeed, he generates both an otherworldly wisdom and a sadness that holds the film together. This is a Merlin that, as John Boorman has clearly intended, shakes any cliche image of the figure in a pointy hat and long white beard. There is an equally fine performance from Helen Mirren as Morgana whose slinky, seductive prowlings have considerable sensuality. It is the two of them that dominate the film. In fact, these two performances overshadow the actors that should have taken charge of the film – Nigel Terry’s Arthur and Cherie Lunghi’s Guenevere – who both remain anonymous and never fill out as characters. Excalibur can also be noted for the presence of a number of then unknown up-and-coming stars, including Gabriel Byrne, Liam Neeson and Patrick Stewart.

Bryan Singer announced a remake of Excalibur during the 2010s, although this has yet to emerge.

Other film versions of the Arthurian legends include:– a Three Stooges spoof Squareheads of the Round Table (1948); the Cinemascope historical adventure Knights of the Round Table (1954); the live-action tv series The Adventures of Sir Lancelot (1956-7); Cornel Wilde’s Lancelot and Guinevere (1963); the Disney animated version with cute animals The Sword in the Stone (1963); the comic cartoon series Arthur and the Square Knights of the Round Table (1966); the big budget musical Camelot (1967); Robert Bresson’s deconstructed Lancelot du Lac (1974); King Arthur, The Young Warlord (1975); the absurdist comedy send-up Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975); the French New Wave Perceval le Gallois (1978); the tv series The Legend of King Arthur (1979); the German tv series Merlin (1980); the dreary TV mini-series Arthur the King/Merlin and the Sword (1981); the Wagnerian opera Parsifal (1982); the tv series Merlin of the Crystal Cave (1991); the animated tv series King Arthur and the Knights of Justice (1992-3); a modern updating October the 32nd/Merlin (1992); Arthur’s Departure (1994) about time travellers attempting to snatch King Arthur; First Knight (1995), which retells the story as a non-fantastical romance; Kids of the Round Table (1995), a children’s version that retells it in schoolyard terms; Lancelot, Guardian of Time (1997) with a time-travelling Lancelot; the tv mini-series Merlin (1998), which tells the story from Merlin’s point-of-view and its sequel Merlin’s Apprentice (1996); the tv movie Merlin (1998) with Jason Connery as the young wizard; the animated Quest for Camelot (1998), which concerned the daughter of one of the Knights of the Round Table; The Excalibur Kid (1999) in which a child is transported back in time to Arthur’s court; Merlin: The Return (2000) in which Arthur and the knights are revived in the present; the revisionist tv mini-series The Mists of Avalon (2001), which tells the story from the perspective of the women; the tv movie Young Arthur (2002); the historical spectacular King Arthur (2004); The Last Legion (2007), an historical spectacular that acts as a prequel to the Arthurian saga; the tv series Merlin/The Adventures of Merlin (2008-12); Merlin and the Book of Beasts (2008); the tv series Camelot (2011); King Arthur: Excalbur Rising (2017); Guy Ritchie’s big-budget King Arthur: Legend of the Sword (2017) starring Charlie Hunnam; and The Asylum’s mockbuster King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table (2017), which places the Knight of the Round Table in the present-day; the modernised The Kid Who Would Be King (2019); and Arthur & Merlin: Knights of Camelot (2020). Other variants include the lowbrow comedy foil of Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889), filmed variously in 1921, 1931, 1949, 1979 and 1989. Parts of the myth have turned up in various films and particularly tv series – Merlin (played by Ringo Starr) as an advisor to various Famous Monsters in Son of Dracula (1974); The Round Table turned up in an episode of Robin of Sherwood (1983-6); Merlin and Lancelot appeared in the present day in an episode of The Twilight Zone (1985-7); the Doctor Who episode Battlefield (1989) attempted a science-fictional retelling, while Transformers: The Last Knight (2017) revealed the Knights of the Round Table were Transformers and Hellboy (2019) featured a revived Merlin and had Hellboy wielding Excalibur; and various series have played the myth out in various futuristic settings – against a post-holocaust dictatorship in Knights of God (1987) and as a puppet space opera in Space Knights (1989). Of all of these, Excalibur is the finest.

John Boorman’s other genre films are:– the startling backwoods brutality film Deliverance (1972); the pretentious sf film Zardoz (1974) (1974); the notoriously pilloried but not entirely uninteresting Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977); the mystical environmentalist film The Emerald Forest (1985); and the doppelganger film The Tiger’s Tail (2006). Boorman also produced the strange fantasy film Dream One/Nemo (1984). In the early 2000s, Boorman announced plans for an animated remake of The Wizard of Oz, although this has yet to be greenlit.

Trailer here