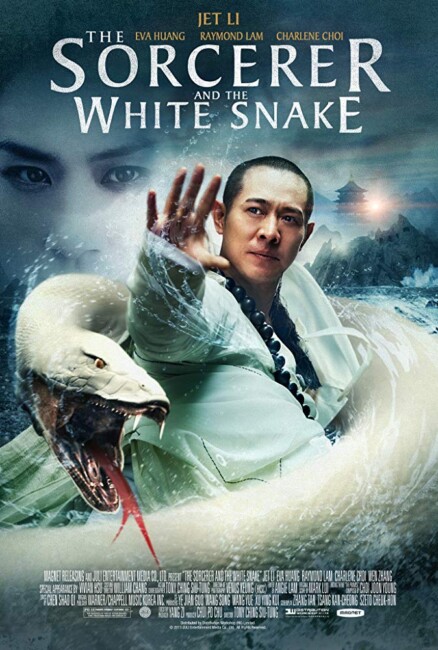

(Bai She Chuan Shuo)

China/Hong Kong. 2011.

Crew

Director – Tony Ching [Ching Siu-Tung], Screenplay – Szeto Cheuk Hon, Tsang Kan Chong & Zhang Tan, Based on Madame White Snake, Producer – Chui Po Chu, Photography – Venus Keung, Music – Mark Lui, Visual Effects Supervisors – Cuby Lee Chung Bok & Sunny Ryu Hee Jung. Production Company – Juli Enterrainment Media Co., Ltd.

Cast

Jet Li (Abbot Fahai), Shengyi Huang (White Snake/Susu), Raymond Lam (Xu Xian), Charlene Choi (Green Snake/Qingqing), Zhang Wen (Neng Ren), Vivian Hsu (Snow Demon)

Plot

The demon Green Snake or Qinqing decides to cause mischief by scaring a group of peasants as they pick herbs. She causes one of the herbalists Xu Xian to fall into the river, whereupon her sister White Snake or Susu appears in human form and kisses Xiu Xian to save him. Afterwards, White Snake realises that because she used her Life Essence to save Xiu Xuan the two of them are now connected. She becomes romantically obsessed with him. She appears to him in human form where she contrives to make him fall into her arms. Meanwhile, the Abbot Fahai of Jinshan Temple is on a single-minded mission to hunt down demons and drive them back to the netherworld. His apprentice Neng Ren is bitten and infected after a fight with a bat demon. Green Snake appears and encourages Neng Ren to surrender to demon form. Abbot Fahai then discovers that White Snake is posing as a human. Certain that romance between demon and mortal can only spell disaster, he determines to drive her back to the spirit realm.

Wu Xia cinema is something that flabbergasts most Westerners who view the films. The Wu Xia film is typified by a series of extravagantly fantastical moves where swordsmen fly through the air or bounce off trees, where demons and witches are dealt with using power blasts, bizarre appropriated weaponry and aspects of eastern beliefs in a series of moves that. The genre emerged from among the Hong Kong martial arts and swordsmen films of the 1960s and 70s, becoming increasingly more fanciful towards the end of the 1970s in filmmakers’ desire to add something novel to the mix. However, it was with films of the 1980s such as Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983), Mr Vampire (1985), A Chinese Ghost Story (1987), Swordsman (1990), Saviour of the Soul (1991) and a great many others that the genre gained its legs.

The traditional Wu Xia died away towards the end of the 1990s, about the time that Hong Kong went back into China’s hands. A funny thing then started to happen. First there was the success of The Matrix (1999) where the Wachowski Brothers copied Wu Xia moves with extraordinary effect. This was followed by Ang Lee wowing the whole world by reinventing the genre as art in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000). This saw the Wu Xia genre taken over by Chinese producers who delivered films on much more lavish budgets than the originals with the likes of Zhang Yimou’s Hero (2002) and House of Flying Daggers (2004), and other efforts such as The Banquet/Legend of the Black Scorpion (2006), 14 Blades (2010), Reign of Assassins (2010), True Legend (2010), Wu Xia (2011), The Grandmaster (2013), The Monkey King (2014) and sequels and League of Gods (2016). Directors from the original Hong Kong fad were employed with Tsui Hark making Seven Swords (2005), Detective Dee and the Mystery of the Phantom Flame (2010) and sequels, Flying Swords of Dragon Gate (2011) and Journey to the West: Demon Chapter (2017). and A Chinese Ghost Story director Ching Siu-Tung (hiding behind the more Anglicised name Tony Ching) here.

The Sorcerer and the White Snake is based on the Chinese legend Madame White Snake/Legend of the White Snake. The story originated out of oral tradition and was first published in 1620, having been told in a number of different forms since, including being adapted into an opera. The story sets down the essential basics involving the two demon spirits White Snake and Green Snake, White Snake’s becoming romantically swayed by the mortal scholar Xiu Xian and the Abbot Fahai’s determination to despatch them back to the spirit world.

The story has been filmed a number of times – as a Japanese adaptation Madame White Snake (1956), a Japanese anime Panda and the Magic Serpent (1958) and a Hong Kong-made opera adaptation Madame White Snake (1962). The most well-known film version was Tsui Hark’s Green Snake (1993), a lush playful version made at the height of the 1990s Hong Kong Wu Xia cycle. This is yet another – the only quibble that one has about the English-language title The Sorcerer and the White Snake is that there is no sorcerer in the film.

The Wu Xia films made since Hong Kong went back to China have been marked by a sweeping lushness due to the bigger budgets afforded by Chinese funding. These are works that seem intended by China for international arthouse and festival audiences rather than pitched to the populist pulp of the earlier Hong Kong films. (One surprise about The Sorcerer and the White Snake given its Chinese backing is the strength of the Buddhist themes, which are far more prominent than they ever were in most traditional Wu Xia).

The other notable thing that is evident in many efforts such as The Storm Riders (1998) and Detective Dee and the Mystery of the Phantom Flame and especially the Monkey King films and others of the 2010/20s is how modern Wu Xia is increasingly taking on board the CGI revolution. This is extensively used here, although with mixed effect. Some of the effects are uneven – especially when it comes to the giant snakes engaged in combat. Moreover, the CGI makes the Wu Xia seem too easy – it was a good deal more amazing watching combatants take to the air and bounce around rooms when you knew it was all being conducted by wire work and choreography whereas with CGI you know that anything is possible and it starts to seem less impressive. On the other hand, Ching Siu-Tung adapts to this is in unique ways that allow traditional Wu Xia to blossom.

Ching Siu-Tung uses the opportunity afforded by the CGI to fill the film with images of the two snake sisters drifting through impossibly Edenic landscapes. He really opens the film up during the sequence with Jet Li pursuing the bat demon where we see Li cruising through the canals of the town on a small boat that seems propelled by his Buddhist awesomeness alone whenever he stands in the prow and then pursuing the demon up into the air by bouncing off the roof of the temple, grabbing its tail and flying off through the mountains and down into Hell, before he despatches and triumphantly lands in a pose on a rock in the midst of a pit of lava.

The bigger budget allows Ching to throw in some gloriously fantastical images – Zhang Wen sporting a pair of bat wings to appear and snatch Charlene Choi away from peril; Jet Li walking through the plague-ridden town and casting a magic dust that allows him to see through the walls as the demons crouch on the bodies of the dying sucking up their lifeforce, before luring the fox demons away and standing calmly as they mob and try to seduce him in female form; the climax with Jet Li and Shengyi Huang battling, she wielding vast tsunamis around his meditating form before he manifests golden Buddha hands that snatch her up and then build a pagoda from the dirt in which to imprison her.

Especially magnificent is the image of the temple flooded, the monks sitting around the altar underwater holding their hands trying not to break the chain as they meditate to deliver the demon possessing Raymond Lam, while outside the giant White Snake tries to batter in but is kept away by a prayer pasted across the door, before an army of mice come up through the floor and free Lam.

On the minus side, Ching draws on the goofy humour of Hong Kong cinema, which seems dated when served up in 2011 – scenes with Shengyi Huang on a pagoda where she uses her tail to destroy the pier to abandon her and Raymond Lam in the middle of the river and force him into her arms, or the scenes as Charlene Choi tries to encourage Zhang Wen in his transformation into a bat creature. The funniest scene is where Shengyi Huang invites Raymond Lam back to meet her family so he can obtain their permission to marry him where the family are played by other animals’ spirits who have a disconcertingly funny habit of reverting to animal form at the most inopportune moments.

Ching Siu-Tung’s other films are:- Duel to the Death (1983), The Witch from Nepal/The Nepal Affair (1985), A Chinese Ghost Story (1987), A Chinese Ghost Story II (1990), A Terracotta Warrior (1990), A Chinese Ghost Story III (1991), New Dragon Gate Inn/Dragon Inn (1992), Swordsman II (1992), The Heroic Trio (1993), The Heroic Trio II: Executioners (1993), The Mad Monk (1993), Swordsman III: The East is Red (1993), The Scripture With No Words (1996) and Jade Dynasty (2019). Siu-Tung is also known as an action choreographer par excellence and has coordinated sequences on films like Shaolin Soccer (2001), Invincible (2001), Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004) and In the Name of the King: A Dungeon Siege Tale (2007).

Trailer here