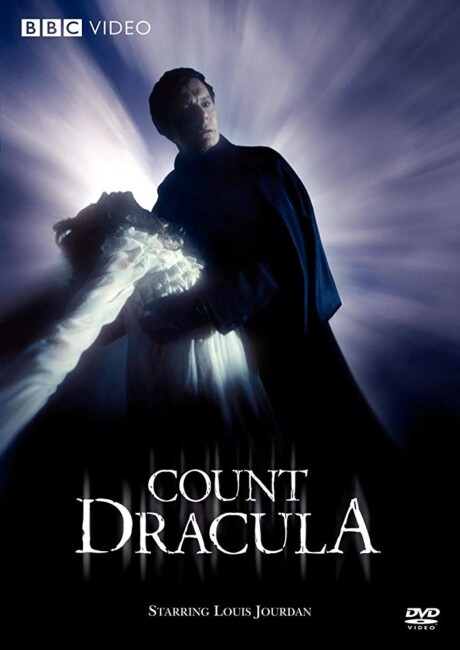

UK. 1977.

Crew

Director – Philip Saville, Teleplay – Gerald Savory, Based on the Novel Dracula by Bram Stoker, Producer – Morris Barry, Photography – Peter Hall, Music – Kenyon Emrys-Roberts, Visual Effects Design – Tony Harding, Makeup – Suzan Broad, Production Design – Michael Young. Production Company – BBC.

Cast

Louis Jourdan (Count Dracula), Frank Finlay (Professor Van Helsing), Susan Penhaligon (Lucy Westenra), Judi Bowker (Wilhelmina Westenra), Bosco Hogan (Jonathan Harker), Mark Burns (Dr John Seward), Jack Shepherd (Renfield), Richard Barnes (Quincey P. Holmwood), Susie Hickford, Belinda Meuldijk & Sue Vanner (Brides of Dracula), George Raistrick (Bowles), Ann Queensberry (Mrs Westenra), George Malpas (Skipper Swales)

Plot

It is 1892. Jonathan Harker travels from England to Castle Dracula in Transylvania to conduct the transfer of the title of Carfax Abbey for Count Dracula. Although the locals fear the castle, Jonathan finds Dracula to be a courteous host. Soon after arriving, Jonathan realises that Dracula has made him his prisoner and is a vampire. Back in England in Whitby, following the crash of a ship on the shore, Jonathan’s fiancee Mina Westenra begins to find strange things about her sister Lucy. She discovers Lucy sleepwalking and with Dracula bent over her in the graveyard. Soon after, Lucy falls ill and two puncture marks are found at her neck. Professor Van Helsing is brought in but, despite his radical methods, Lucy dies. Van Helsing takes them to the graveyard where he explains that Lucy has become a vampire and must be staked to save her soul. They then set out to eliminate the menace of Dracula. Dracula meanwhile has set to feasting on Mina and making her his next victim.

Count Dracula was a BBC tv production that set out to remake Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). It was around the fifth adaptation of the book up to that point – following the unofficial German version, the silent classic Nosferatu (1922) with Max Schreck, the Bela Lugosi Dracula (1931), Hammer’s Dracula/The Horror of Dracula (1958) with Christopher Lee, the cheap European version Count Dracula (1970) also with Christopher Lee and the US tv movie Dracula (1974) with Jack Palance. Count Dracula was originally aired as a single 150-minute tv play, although almost all other screenings split it into either two parts or three one-hour segments with commercials. The IMDB incorrectly gives the impression that this was an episode of the long-running US PBS arts channel program Great Performances (1971– ) where in fact it was merely broadcast there following its original UK airing.

Count Dracula came around the time that the vampire film was trying to address the modern day. Starting a few years earlier, there had been a spate of films such as Count Yorga, Vampire (1970), Dracula A.D. 1972 (1972), The Night Stalker (1972), George Romero’s Martin (1976) and Salem’s Lot (1979) that tried to place the vampire, cape and all, into the modern day. The era also saw films such as Vampira/Old Dracula (1974), Tender Dracula (1974), Dracula, Father and Son (1976), Love at First Bite (1979), Mama Dracula (1980) and Once Bitten (1985) that spoofed the traditional image of the vampire. At the same time, there were the likes of Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire (1976) and the Frank Langella version of Dracula (1979) that started to explore the romantic, sensual side of the vampire, something that soon began to blossom as a major alternate take resulting in a dearth of vampire erotica and romance, the culmination of which was the Twilight (2008) phenomenon. You can see the beginnings of that here – the mini-series is notedly subtitled ‘A Gothic Romance Based on Bram Stoker’s Dracula‘ on its opening credits.

There is the sense that comes across in several of the 1970s versions of Dracula and Frankenstein (1818) of the people behind them trying to turn away from the Universal and Hammer adaptations that had dominated cinematic treatment of the respective stories up to that point and to go back to the original source material. The 1970s saw no less than four versions of Dracula – the 1970 Jess Franco version, the 1974 Jack Palance version, this and the 1979 Langella version – and four of Frankenstein, more versions of either than in any other decade in cinematic history. In these, there seems a concerted effort to forget about Lugosi, Lee, Hammer and Universal and go back and find new things in the book.

The clear model for Count Dracula could well have been the US tv mini-series Frankenstein: The True Story (1974), which restored the book to its Victorian setting, gave us back an articulate creature and many aspects that no other film version had. It seems that Count Dracula has been largely motivated by the desire to retell the story the way Bram Stoker did without any additions, elaborations or reinventions. While the mini-series does make the odd change – Lucy and Mina become sisters, Holmwood and Quincey are compacted into one character – what we have could be considered the most faithful adaptation of Dracula to date.

Count Dracula is very much a 1970s British television version of Bram Stoker. This is a period where almost all British tv shows were shot on video in in-house studios (as opposed to most US television shows of the period that were shot on film). Thus we get a no-nonsense period rendering with an emphasis on everyday realism as opposed to a cinematic flourish and its tendency to overdramatise or produce a work for visual appeal. The mini-series does manage a few outdoor locations, although the lack of lavish budget makes the Borgo Pass and Transylvania look very much like regular British countryside. On the other hand, this is, as far as I am aware, the only version of Dracula to have gone and shot on location in the seaside town of Whitby where much of the book is set.

The upshot of this is the feeling that the production renders the book in fairly much the way and milieu that Stoker would have imagined the story when he wrote it. With the Hammer Draculas and subsequent variations, especially Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) and the tv series Dracula (2013-4), you get very much the sense that the story has been transplanted into an extravagant fantasy version of Victorian England where the production and costume designers have run rampant and come up with the most gorgeous visions and texture they can. There is none of that here – this is, you feel, an ordinary and everyday world, not one designed to wow and constantly impress the eye with its art dressings and costumes.

With filmed versions of Dracula, it seems as though adapters are either stuck with remaining faithful to the story or else opening it up. By and large, the most successful versions of the book – Nosferatu, the Hammer version and Coppola – are ones that allow their respective directors to not worry too much about treating the story faithfully. Count Dracula is the only version that manages a judicious balance of both. Director Phillip Saville renders the scene where the wives appears to Jonathan and Dracula drives them away as too mundane and ordinary – almost every other version has made this into something supernatural (as per the Lugosi version) or seductive (as in Hammer and especially the Coppola version). On the other hand, in the next scene, Saville gives us what would have been an undeniable shock image for television audiences of the day – of Dracula returning and bringing a baby out of a bag for the wives to feed on and we next seeing them with bloodshot eyes.

There is an excellent scene where Jonathan invades Dracula’s crypt and comes across the wives lying in open coffins, their blood red eyes open and aware of him being there but they not moving, before he comes to Dracula’s coffin and picks up a shovel at which point Louis Jourdan simply turns and smiles at him. One of the most vivid scenes is where Susan Penhaligon is drawn out of her sleep and through the town sleepwalking, before a following Judi Bowker comes across her draped across a tombstone being ravaged by Dracula who turns into mist and flees as she comes.

One of the major changes is when it comes to the climactic scenes where Van Helsing, Seward, Harker and the others follow Dracula across Europe back to his castle using a hypnotised Mina to track his progress. She is not hypnotised here, merely seems to have innate knowledge, while the cross-Europe journey is scaled down. Nevertheless, Saville comes up with one fine original scene where Van Helsing (Frank Finlay) and Mina (Judi Bowker) are stopped in the woods for the night, Dracula’s wives approach and Van Helsing makes a protective circle of crumbled communion wafer around them, only to then find that the half-vampirised Mina is unable to step over it and come to him.

This is also an adaptation that taps into the sexual undercurrents of the book in ways that you feel Bram Stoker intended and without blowing them all out of proportion (as you could accuse Coppola of). The two girls (Susan Penhaligon and Judi Bowker) are rightly seen as the ideal of Victorian brides in waiting, perfectly mannered and sweetly innocent whom Dracula proceeds to plunder. There are fine scenes where Susan Penhaligon waits in bed for Dracula to come and ravage her; or later of her unbuttoning her gown and lying back to wait on a chaise-lounge, greeting him half-naked and later being found draped across the side of the bed, delirious and gasping in what it implied as being post-orgasmic bliss. Later there is the striking scene where Dracula appears to Judi Bowker and she accepts him to her bed as her husband Bosco Hogan lies asleep beside her all the while.

In being an extremely faithful version of the book, the mini-series adheres more to the way that Bram Stoker used Dracula as a dramatis personae – he was present as a character in the opening Transylvania prologue but upon the return to England was relegated to a shadow, operating from the sidelines but with almost no direct interaction with the rest of the characters. All of the other film adaptations have compensated for this by writing more scenes for Dracula. The mini-series comes up with only one – where Van Helsing and Seward come across Dracula in one of his houses and try to drive him away. Oddly, this is a scene where the cross is shown having no effect at all, although Phillip Saville does deliver one vivid image where Louis Jourdan stands there and the light of the crucifix casts a piercing pattern perfectly situated right between his brow and nose.

Cast in the title role is Louis Jourdan, a French-born actor who had a Hollywood career as suave foreigners and seducers in a career going back to the 1930s. (It is hard to believe seeing Jourdan’s dashing Dracula here that he was in his mid-fifties at the time). Bela Lugosi played into the caricature of Dracula as a foreigner. Jourdan refines this and takes it more back towards what Stoker intended of Dracula as the courteous host. When we first meet him, Jourdan gives Dracula an unidentifiable foreignness that we can’t quite pinpoint. That and a controlled precision and a dangerous charm.

Frank Finlay bravely takes on Van Helsing’s Dutch accent – one of the more agonising parts to read in the book – and comes out not too badly. Susan Penhaligon is one of the cutest genre actresses of the 1970s Anglo-horror era. On the other hand, she seems just a little too girlish when it comes to going from sweet innocent to ravening vampire seductress. The single worst piece of casting however is Richard Barnes whose character is designed as a combination of both Arthur Holmwood and the Texan Quincey Holmes. Barnes’s efforts to open up with a broad Texan accent are grating and atrocious.

This version of the story is not perfect. The budget gets in the way. The scene with Dracula walking up the wall of his castle is rendered but rather absurdly looks like it is Louis Jourdan attempting to do the butterfly stroke on dry land. The bat effect looks like the same cheesy bat hanging on a wire that we had in Scars of Dracula (1971). The most dated effect though is the use of tinted and solarised footage of Louis Jourdan’s face and eyes in closeup to represent Dracula vision.

Other adaptations of Dracula are:– the uncredited classic German silent Nosferatu (1922); Dracula (1931), the classic Universal adaptation starring Bela Lugosi; the Spanish language version Dracula (1931) shot on the same sets as the Lugosi version starring Carlos Villarias; Hammer’s classic Dracula/The Horror of Dracula (1958) with Christopher Lee; Dracula in Pakistan (1967), an uncredited remake of the Hammer film; Count Dracula (1970), a cheap continental production that also featured Lee; Dracula (1974), a cinematically-released tv movie starring Jack Palance; Dracula (1979), the lush romantic remake with Frank Langella; Werner Herzog’s remake Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) with Klaus Kinski; Francis Ford Coppola’s visually ravishing Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), featuring Gary Oldman; the modernised Italian-German Dracula (2002) starring Patrick Bergin; Guy Maddin’s silent ballet adaptation Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary (2002); Dracula (2006), the BBC tv adaptation starring Marc Warren; the low-budget modernised Dracula (2009); and Dario Argento’s Dracula (2012) with Thomas Kretschmann as Dracula; the low-budget Canadian Terror of Dracula (2012) with director Anthony D.P. Mann as Dracula; the tv series Dracula (2013-4) with Jonathan Rhys Meyers; the BBC mini-series Dracula (2020) starring Claes Bang; Bram Stoker’s Van Helsing (2021), which actually features no Dracula; The Asylum’s Dracula: The Original Living Vampire (2022) with Jake Herbert, which actually features no Dracula; and the remake of Nosferatu (2024) with Bill Skarsgård.

Director Philip Saville has a career in British television that goes back to the 1960s, his most famous work being the hit mini-series The Boys from the Blackstuff (1982). Saville has made a number of other genre tv mini-series, including The Life and Loves of a She-Devil (1986), the famous quasi-fantastical Fay Weldon feminist work about a woman’s revenge; First Born (1988) and a further Fay Weldon adaptation The Cloning of Joanna May (1991), both about cloning; and the Hallmark biopic My Life as a Fairytale: Hans Christian Andersen (2001). Saville rarely ventured into film and the occasions he did were little-seen, including the strange Shadey (1985) about a man with psychic powers; The Fruit Machine (1988) about gay youths pursued by a killer; and the drama Metroland (1997).

Full mini-series available here