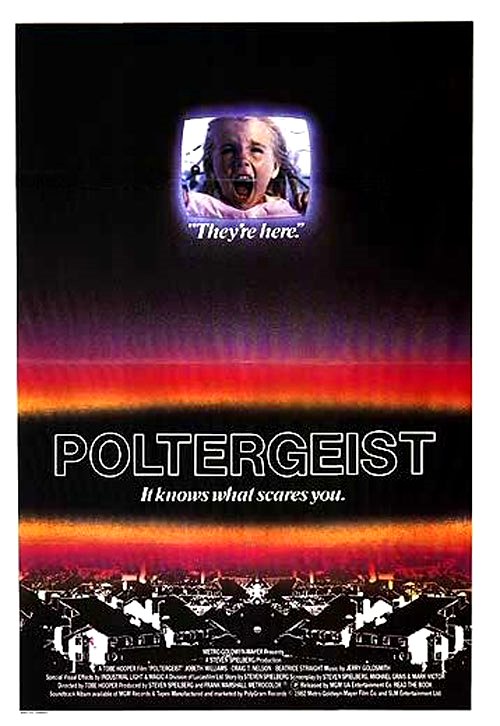

USA. 1982.

Crew

Director – Tobe Hooper, Screenplay – Michael Grais, Steven Spielberg & Mark Victor, Story – Steven Spielberg, Producers – Steven Spielberg & Frank Marshall, Photography – Matthew F. Leonetti, Music – Jerry Goldsmith, Visual Effects – Industrial Light and Magic (Supervisor – Richard Edlund), Mechanical Effects – Michael Wood, Special Effects – Jeff Jarvis, Makeup Effects – Craig Reardon, Production Design – James H. Spencer. Production Company – MGM.

Cast

JoBeth Williams (Diane Freeling), Craig T. Nelson (Steve Freeling), Beatrice Straight (Dr Martha Lesh), Zelda Rubinstein (Tangina Barrons), Oliver Robbins (Robbie Freeling), Dominique Dunne (Dana Freeling), Heather O’Rourke (Carol Ann Freeling), Richard Lawson (Ryan), James Karen (Teague)

Plot

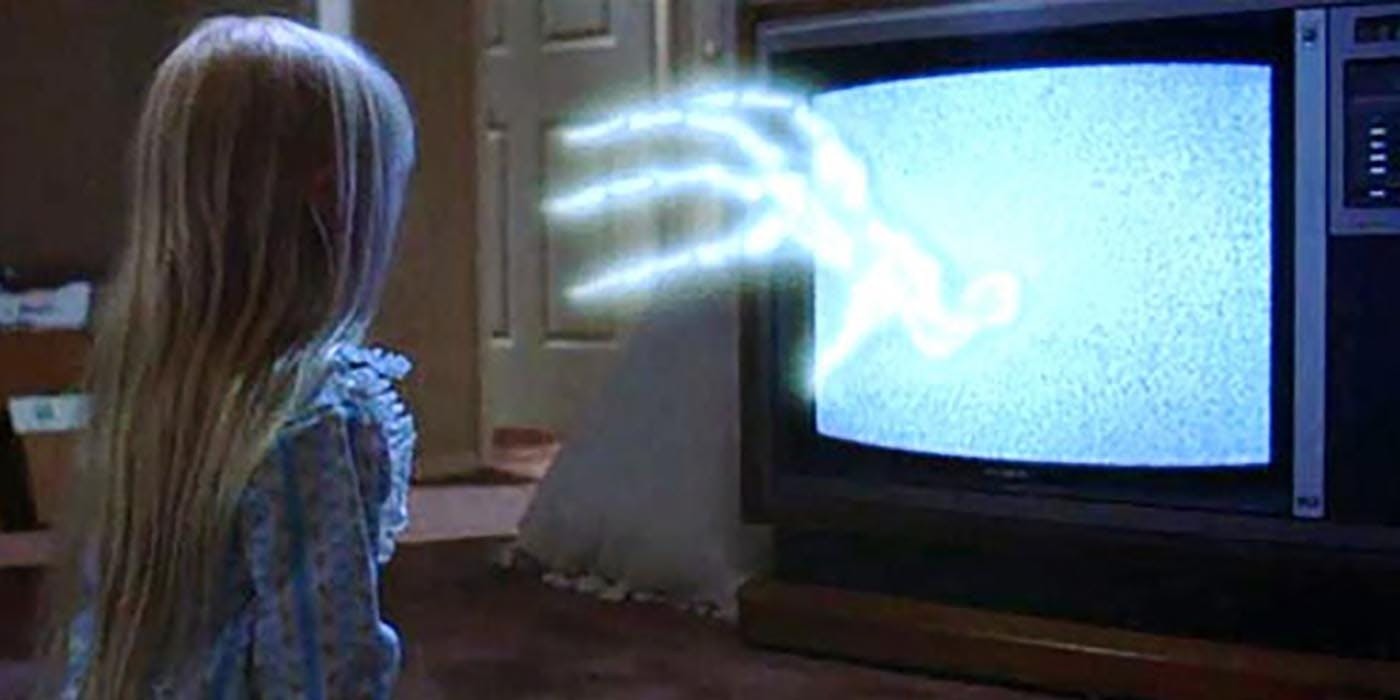

Realtor Steve Freeling and his family have moved into a new house on the Cuesta Verde development estate. They then realise that their new house is haunted. This at first proves amusing. However, in the midst of a storm, their youngest daughter Carol Ann is sucked into the closet. Her disembodied voice comes to them from inside the tv set, pleading for help. Joined by a team of parapsychologists and a medium, they attempt to rescue Carol Ann from the demonic forces holding her prisoner in the realm beyond.

By the 1970s, the haunted house and ghost story genre was beginning to seem dated. Although many people assume that it grew out of the 1930s and 40s, the haunted house film never existed as a genre during this period – in fact, during Hollywood’s Golden Age of Horror the haunted house was conspicuous by its thematic absence and there was no serious Hollywood haunted house film until The Uninvited (1944). Since then the haunted house film has remained of sporadic interest, with peaks such as The Haunting (1963) and The Legend of Hell House (1973). By the 1970s, the haunted house had, with occasional exceptions, mostly become the stuff of tv movies.

The 1980s did bring a reinvigoration with the high profile likes of The Amityville Horror (1979) and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), both of which were haunted house films by dint of trying to be more than that – The Amityville Horror tried to paint itself as a true story, while The Shining stood outside of easy genre confines. The only films in the classic mold were The Changeling (1980) and Ghost Story (1981), which both pitched themselves to the older age group and seemed dated in their sedately mannered thrills.

That was until Steven Spielberg reinvented the genre with Poltergeist. In the same way that Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) had placed a new spin on alien encounters by having aliens come to visit suburbia in a wondrous communion of magic and soft lights, so too Poltergeist regenerated the ghost story by taking it out of the Gothic mansion and relocating it in suburbia amid a wondrous array of Industrial Light and Magic supernatural effects. A number of other films quickly copied such a move.

Poltergeist was the first of Steven Spielberg’s films where he acted as Executive Producer for other directors. The director he brought on board was Tobe Hooper. Tobe Hooper became a cause celebre several years earlier with the brutal shock classic The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), which made audiences and censors everywhere sit up in alarm. Since then, Hooper’s output wavered between an obscure attempt to repeat Texas, Eaten Alive/Death Trap (1977), the quite good Stephen King tv mini-series Salem’s Lot (1979) and a venture into the slasher/boogie man genre with The Funhouse (1981), before taking on Poltergeist, which became his most mainstream success. (See bottom of page for Tobe Hooper’s other films).

The marriage between Steven Spielberg and Tobe Hooper is an incongruous pairing – there are few directors whose sensibilities are as far away from Spielberg’s own as Hooper. Hooper, for instance, claimed that he received the inspiration for Texas Chain Saw while Christmas shopping and wishing that he could grab a chainsaw and carve up the crowds around him. Yet there are surely few films more removed from such a fantasy of anarchy as Poltergeist, which seems to offer a cozy confirmation of the very values of the middle-classes that Hooper wanted to carve up.

There was a considerable degree of debate when Poltergeist came out who the predominant creative influence was – Tobe Hooper or Steven Spielberg – in that the film closely mimics the directorial style of Spielberg. Both parties remained close-lipped about the nature of the working relationship. In recent years, those on the set have stated that Spielberg did most of the directing allowing Hooper to take credit because he was contractually tied down elsewhere. Other voices – such as Mick Garris in the documentary In Search of Darkness: A Journey Into Iconic ’80s Horror (2019) who visited the set during shooting – come down on Hooper’s side.

In the 1980s, Steven Spielberg in his films Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T. and later with the various directors who worked under his Executive Producership – Joe Dante with Gremlins (1984), Robert Zemeckis with Back to the Future (1985), Matthew Robins with Batteries Not Included (1987), Frank Marshall with Arachnophobia (1990) and Tobe Hooper here – defined a new world, a world whose horizons were middle-class American suburbia and whose history was a culture founded in tv reruns of 1950s science-fiction movies.

Each film beheld a vision of that world coming in touch with the transcendental – be it alien visitors, creatures, ghosts or being able to venture into its own past – a mystery or threat that would touch with amazement and then retreat leaving the lives of the 1950s Baby Boomers and their kids with a sense of closure, having stood in for missing parents or friends, to patch up the generation gap, stand up for the downtrodden, but mostly to provide a sense of religious awe about the mysteries that lay beyond the horizons of suburban expectation. It was a vision that affirmed a cosy comfortable Reaganite America. In Poltergeist, Craig T. Nelson even sits in bed reading Reagan: The Man, The President (1980) while smoking a doobie – there is probably no more potent an image in 1980s cinema of the 1960s radical having been absorbed into middle-class conservatism than this.

Poltergeist is a film that often plays on childhood fears and its most effective parts are early on when it ventures into these – the gnarled proto-human tree in the backyard, thunderstorms, the shadows in the half-open closet, the clown that becomes a grinning monster in the dark, the thing under the bed. It delves into the dark side of the cosy child-like sentimentalism of Steven Spielberg.

Some of the effects that Tobe Hooper serves up are way out. There is the classic scene where an invisible force drags JoBeth Williams all the way around the walls and ceiling of her room. One of the film’s most beautiful scenes is the image of the ghosts descending the staircase – it is a scene where Tobe Hooper forgets about scaring people and momentarily creates an awe-filled vision of the afterlife. The film delights in upstaging the parapsychologists, cutting from them talking in amazement about how they observed an object move seven feet in seven hours to open a door into a room filled with flying objects – a scene where Industrial Light and Magic show off with books flapping past and a compass that connects with and starts to play an LP.

As a script, Poltergeist does not make sense. All its effect comes in working as a ghost train ride of gut and emotional effects. Where it falls down is in offering up any coherent explanation of what is going on. Like the aliens in Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the ghosts here seem arbitrarily playful or threatening depending on the particular requirement of the moment. There is a good deal of charm to the initial scenes of chairs moving and being found stacked up on tables when people’s backs are turned.

However, Poltergeist is a film that has been construed without any rhyme or reason – it is just a haunted house ride with pop-up effects jumping out at you at every opportunity. There is no connection ever established, for instance, between the Indian burial ground, the housing tract where the headstones have been moved without the graves being dug up, and the gateway to Hell that for some reason wants young Carol Ann, or even any explanation of why she vanishes through the closet and somehow ends up inside the tv. It is, for example, hard to believe that an entire housing estate could be built without builders and excavators digging into the ground and discovering the coffins still there. Nevertheless, as a cinematic equivalent of a fairground haunted house ride, there are few other ghost stories that are such unabashed fun.

The film assembles an exceedingly fine cast. The usual suburban everyperson characters of a Steven Spielberg film are given some winning playings by JoBeth Williams and Craig T. Nelson. Craig T. Nelson, who has always managed to come across as cross-eyed and rather dopey in subsequent parts, probably has his best ever role here (at least up until he played Mr Incredible). JoBeth Williams is great and they receive marvellous support from Beatrice Straight in an eccentric spinster auntie role.

The scene-stealer is 4’3″ Zelda Rubinstein as the piercingly authoritarian and spookily prescient Southern Baptist psychic, strutting through the film muttering arcane omens. She captures the show from the moment she appears halfway through. Interestingly, the film allows her character to swing between some ambiguous extremes – she is at times a decidedly sinister figure, which the film never deigns to explain. (One never quite worked out what was going on during the scenes where she is advising Carol Ann to go into the light).

There were two disappointing sequels, Poltergeist: The Other Side (1986) and Poltergeist III (1988). All the regulars from this film appear in the second with the exception of Dominique Dunne who was murdered by her boyfriend shortly after Poltergeist came out; only Heather O’Rourke and Zelda Rubinstein appear in the third. Poltergeist (2015) is a remake. The Canadian tv series Poltergeist: The Legacy (1996-9) about an organisation fighting the occult is unrelated. Poltergeist was parodied in Scary Movie 2 (2001).

Subsequent to Poltergeist, Tobe Hooper went onto make several other A-budget sf films with Cannon – the enjoyable psychic alien vampire film Lifeforce (1985), the remake of Invaders from Mars (1986) and the underrated The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986). In the 1990s, the slump of Tobe Hooper’s career has been sad to see, his work having included the dire pyrokinesis film Spontaneous Combustion (1990), the haunted dress tv movie I’m Dangerous Tonight (1990), an episode of the John Carpenter anthology Body Bags (tv movie, 1993), the erotic film Night Terrors (1993), the awful Stephen King adaptation The Mangler (1995), the weird apartment dwellers black comedy The Apartment Complex (1999), the monster movie Crocodile (2000), the slasher film Toolbox Murders (2003), Mortuary (2005) and Djinn (2013).

Trailer here